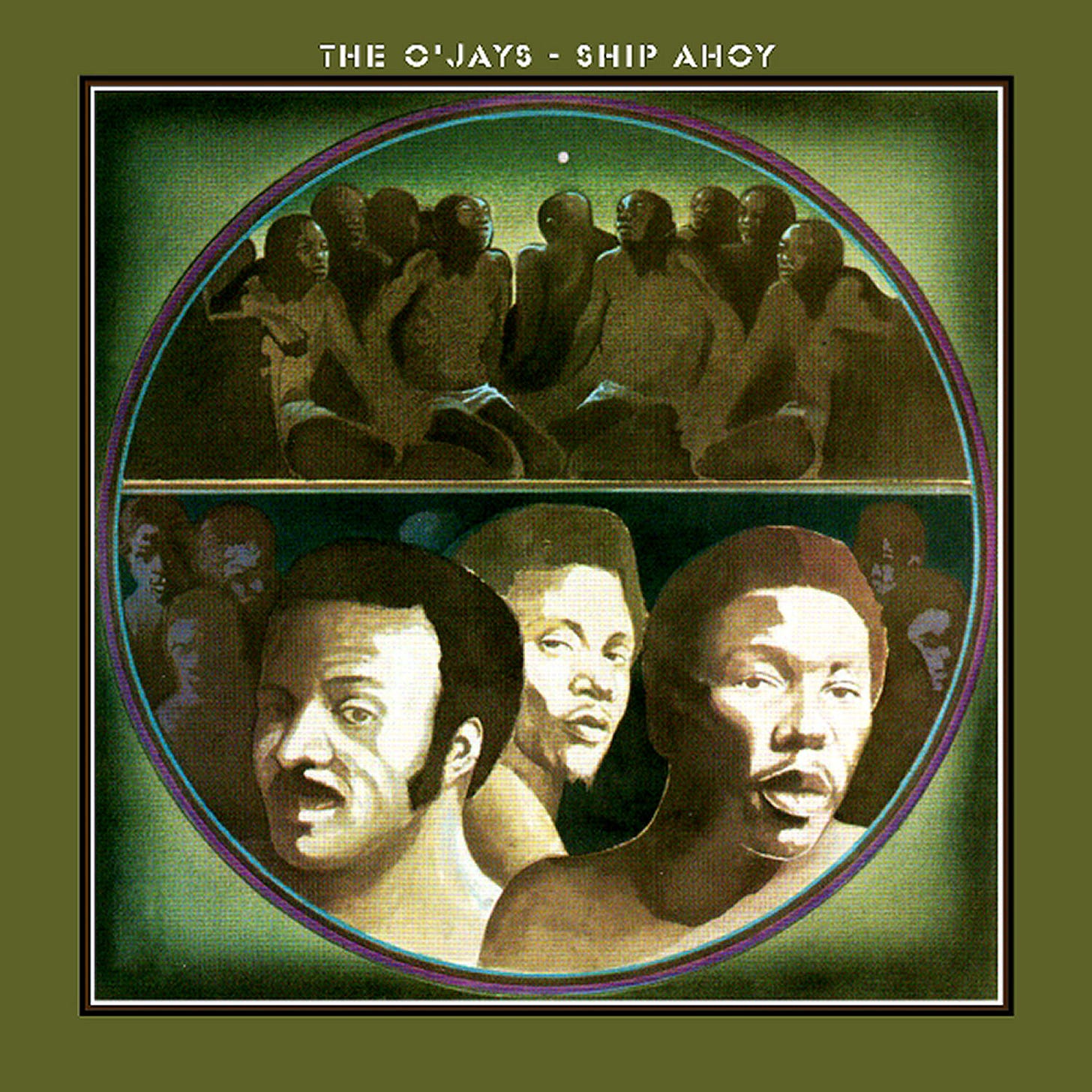

The Middle Passage: Ship Ahoy

Produced by the duo Gamble & Huff, Ship Ahoy featured a cover depicting the group’s three members among enslaved Africans crammed into the hold of a slave ship.

In 1973, The O’Jays, a group from Canton—a steelmaking city in Ohio—released Ship Ahoy, their second album on the Philadelphia International Records label. Produced by the duo Gamble & Huff—famed for popularizing the “Philadelphia Sound” and paving the way for disco—it featured a cover depicting the group’s three members among enslaved Africans crammed into the hold of a slave ship. Its era is telling: a deeply affecting track of more than nine minutes that opens with the ship’s timbers creaking, joined by the ominous rumble of the ocean. Rooted in a long tradition of African American songs denouncing slavery, Ship Ahoy honored the memory of millions of women and men torn from the African continent. “That was our version of the Middle Passage,” Kenny Gamble explained. “Huff and I both went to Ghana to see the slave fortress. We stood in front of the Door of No Return, which led you straight onto the slave ship. Once on board, it was over—you were finished. No more family, no more children, no more wife. You were snatched from your life, put in irons, and sold off like livestock, like a donkey or whatever.”

When, in 1619—one year before the Mayflower and its “Pilgrim Fathers”—the first enslaved Africans arrived in the English colonies at Jamestown in what is now Virginia, the European powers had already been deporting Africans for more than a century. Everywhere, “Negroes” served as a specious rhetorical device used to justify the unjustifiable. “Black men were brought here as beasts of burden. They were indispensable to the economy. To justify treating men like animals, the white republic convinced itself they really were animals, deserving of such treatment,” lamented author James Baldwin, quite rightly. It was this idea of difference that set the Atlantic slave trade apart from other forms of slavery stretching back to antiquity. The distinctive feature was not only the number of victims or how long it lasted but also the intrinsic violence of the New World’s capitalist plantation system. From 1619 to 1865, slavery was simultaneously an unparalleled source of profit, the justification for wealthy southern planters’ lopsided political power (their voices dominated Congress), and a horrifying display of the contradiction between the nation’s founding principles and its political economy. In other words, it was on the backs of millions of enslaved Black women and men that the United States became the richest nation on Earth.

In a hostile world of racial, social, and economic exploitation—where danger became the norm and violence a daily occurrence—the resilience of deported Africans in preserving their cultural heritage and transforming it into a distinctly American experience remains impressive. Unlike the vast majority of European colonists, they had not chosen to live in America. Though that fact might seem self-evident now, it is worth recalling if we are to grasp the psychological devastation endured by these millions of uprooted women and men. Nevertheless, they managed to create and develop original modes of expression—a distinct culture of resistance enriched by the constraints and conditions they faced wherever they happened to be. It was a culture deeply rooted in oral tradition, where songs served as a refuge and a vehicle of revolt against enslavement and as a vital means for each individual to reassert their African identity. “Black music has always been first and foremost its own story—a culture that unites a people in the extremes of physical, spiritual, and creative survival,” Quincy Jones confirms.

Through their songs, enslaved people conveyed their suffering and fought to change it so that their children might grow up free from the same injustice. They fashioned a language whose meanings eluded anyone lacking the proper codes. Overseers and slaveholders often mistook these songs for passive submission and acceptance of bondage. Yet the bitterness of those in captivity frequently seeped into the music, delivering fierce creative blows against their masters and giving voice to a collective longing for freedom. In this way, they perpetuated the practice of West African choral singing—and, a century after emancipation, these same choral influences could be heard in the work of drummer and composer Max Roach.

“It has always been a tradition for African American musicians to express our perspective and our human, social, and political claims. […] That’s why it’s perfectly natural to use our art as a springboard for expressing them.” As early as 1961, Roach released his album We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite on the Candid label, a radical statement on the circumstances of African Americans in the United States. Rejecting all political euphemism, it included the track “Driva’ Man,” which explicitly invoked the atrocities of slavery. On that piece, Abbey Lincoln’s gripping vocals were at once somber, outraged, and laden with dignity. The tambourine strikes punctuating the song recalled the whippings inflicted daily on enslaved people in the South, transforming Lincoln’s singing into a clarion call for white America to face its own history.

Choppin’ cotton don’t be slow

Better finish out your row

Keep avmovin’ with that plow

Driva’ man’ll show you how

Git to work and root that stump

Driva’ man’ll make you jump

Better make your hammer ring

Driva’ man’ll want to swing

Enslaved Africans on American soil never reconciled themselves to their enslavement. Threats of punishment, mutilation, and even death failed to quell their rebellions. Their resistance took many forms: sabotage, refusing to eat, striking or insulting their owners, and even poisoning their livestock. In 1803, on Saint Simons Island in the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina, a group of Africans collectively drowned themselves rather than live in chains. In the 1820s, the abolitionist and Afro-feminist Harriet A. Jacobs—who had once been enslaved in Virginia but managed to escape—wrote in her autobiography about how her uncle “knocked his master to the ground—one of the wealthiest men in town” before fleeing north. These acts of resistance and self-defense, along with mounting pressure from free Black people on the American government, were what ultimately dismantled the so-called “peculiar institution.”

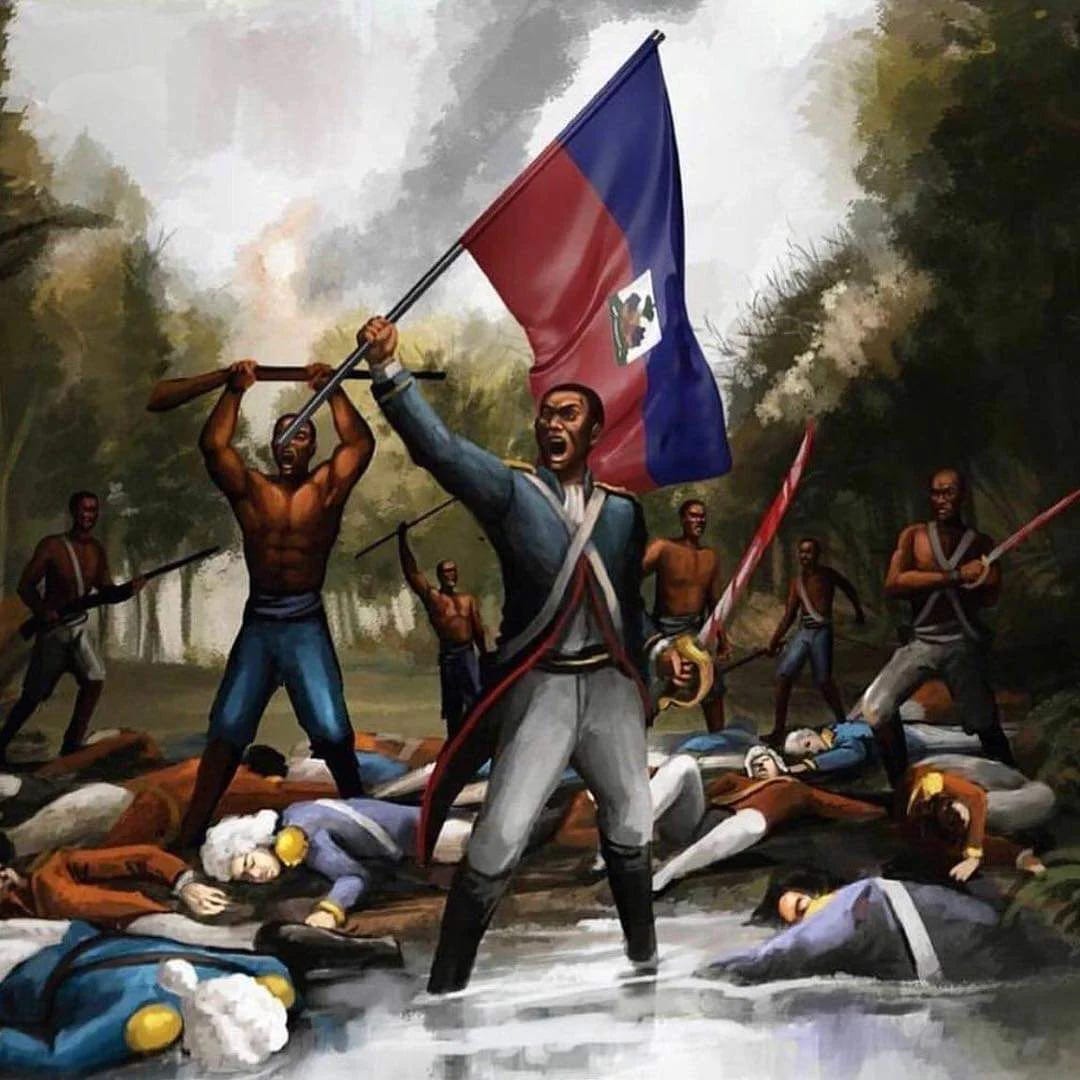

The history of the United States includes more than 250 slave conspiracies and revolts—nearly one per year from 1619 until Emancipation. The most famous was Nat Turner’s uprising in 1831. “Nat Turner’s revolt erupted, and the specter of Blackness threw our city into a frenzy. Strange that slaveholders would suddenly feel afraid, given how ‘content and happy’ their slaves supposedly were. Yet afraid they were,” Harriet A. Jacobs noted with irony before describing the barbaric repression that followed. No Black encampment of that time ever lived in true peace. And just as the Haitian Revolution of 1804 became a beacon of hope and possibility—establishing a society that recognized the right to freedom and citizenship for all—so did its shockwaves resonate among enslaved people in the United States. “When the Black sons of Haiti struck a blow for freedom, they struck a blow for every Black man in the world,” the journalist, philosopher, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass rightly observed.

This ethos of rebellion took on added force because cultural ties still endured even as the conditions for deported Africans in America worsened. As far back as the 16th century, whenever poor whites and enslaved Africans labored side by side, tensions would prompt planters and state authorities (often one and the same) to erect repressive laws to keep them from uniting—knowing such alliances might undermine the entire economic system of the English colonies. Black men were forbidden to bear arms, barred from associating with white women or moving about after dark, and denied literacy. With these “Black Codes,” slavery took formal root as an institution, profoundly altering relations between Black and white people. Concurrently, a peculiar kind of racism emerged—manifesting in myriad ways: hatred, contempt, pity, even partnership—and solidifying the subordinated status of Black people in America for the next 350 years.

The American Revolution changed nothing about the inhumane conditions endured by enslaved Africans. Worse still, the framers of the 1787 Constitution effectively enshrined the “peculiar institution” as property guaranteed to Southern planters by the federal government in cases of rebellion or escape. “When they drafted the principles of democracy, they did more than ignore slavery; they agreed to grow it to strengthen the nation’s coffers,” Martin Luther King Jr. declared in condemnation. As with the Athenian democracy of old, America’s so-called democracy was a myth benefitting a small minority of rich white men—leaving behind Black people, Native Americans, women, and the poor, who together made up more than half of the fledgling nation.

“The leaders of the War of Independence were wealthy white men tired of paying high taxes to the King (of England). This had nothing to do with freedom, justice, and equality for everyone,” said Assata Shakur, the revolutionary Afro-feminist activist and aunt of rapper Tupac Shakur. Still, some Black Northerners found ways to take advantage of the disruption brought by the American Revolution to free themselves. A new Black elite emerged in large cities like Boston and Philadelphia, proudly invoking the Declaration of Independence. Their rallying cry: abolition and equal rights. Under their pressure, slavery was eventually dismantled north of the Mason–Dixon Line—though it was replaced by a system approximating segregation.

No such shift happened in the South, where slavery only grew stronger with the spread of cotton cultivation. Adopting a highly capitalist monoculture demanding massive labor, the South expanded the slave trade as never before. The March 2, 1807 law banning the importation of slaves did nothing to stop it—merely adding to the long record of unenforced measures. Between 1810 and 1860, the number of enslaved people in the South quadrupled, and until 1850, at least 20,000 new captives arrived each year. Even after that, 6,000 more arrived annually until what we call the Civil War. The Clotilda was the last known vessel to complete the Middle Passage, in 1859. By that time, four million people were still enslaved in the United States. Slavery and free-market liberalism had merged seamlessly: By controlling the levers of government, Southern planters retained power over both enslaved people and the destiny of the state itself. In so doing, they preserved the system they had built—amassing ever greater capital and ensuring that capitalism and slavery thrived together.

Such deep entrenchment of slavery in the South could not have taken place without Northern complicity, as Northern bankers who managed the economy also profited handsomely. “Hence the Constitution turned out to be a compromise between the interests of Southern slaveholders and those of Northern business,” White people thereby became the jailers of the system, explaining the long-running over-arming of the white population up to the present day. This ever-growing network of prohibitions forced enslaved people to create new forms of communication—and a renewed sense of community—through music and dance. Double meanings became a survival strategy in that harsh world, a vital weapon for fugitives and their allies. It also allowed them to denounce the myriad injustices that Black people faced daily. Most songs from the slavery era do not really “tell a story;” instead, they accumulate vivid imagery to generate an atmosphere the community itself can understand.

This method of conveying social and political messages—whether concealed or overt—through music has continued in African American compositions to this day. Dizzy Gillespie said as much when he spoke of bebop: “It wasn’t about making political speeches or announcements like, ‘Okay folks, here comes our protest piece now.’ Our music alone was enough to proclaim our identity, carrying in it every message we wanted to deliver.”