The Lineage of Miles Davis and Roy Ayers

Each guide is based on legendary musicians believed to be part of D’Angelo’s roots. It then branches out into post-‘Brown Sugar’ and ‘Voodoo,’ drawn from that tree. Here’s Miles and Ayers.

From a narrow definition of soul music, we highlighted R&B that connects back to artists like D’Angelo, hoping it might spark broader interest. Even if you try to explain that “today’s R&B is a direct continuation of old-school soul,” if people don’t see it on the surface, it makes sense they’d ignore it. Those surface-level impressions might tighten the entrance to R&B more than we realize. At the heart of this lineage, this guide covered albums released from 1995 to 2015 that connect to D’Angelo in different ways.

Each guide is built around legendary musicians believed to be part of D’Angelo’s roots (Prince, Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield, Sly Stone, and so on), then branch out into post-D’Angelo R&B releases that draw from that heritage. Inevitably, the selections are a bit biased. They heavily feature the genre often called “new classic soul” or “neo-soul.” So, out of all the artists who’ve been active these past two decades, we’re only showcasing about 60% of them. Still, we take some pride in how major releases by well-known R&B artists line up alongside indie records cherished by devoted fans.

We hope you’ll understand that any artist or album was left out intentionally—and that the artists appearing in each guide don’t necessarily belong in only that guide. We'll be over the moon if this sparks a whole new R&B world for you.

Jazz and R&B have always stood shoulder to shoulder. Neo‑soul in particular is often sung over tracks that quote jazz riffs, and it is not unusual for the performers themselves to have a grounding in jazz. Although D’Angelo lacked formal jazz training, he gradually absorbed its essence—inviting Charlie Hunter and Roy Hargrove onto Voodoo, for instance. What truly shades contemporary R&B, however, is less straight‑ahead jazz than the soul‑ and funk‑inflected side of jazz musicians—their instinct for crossing genre borders.

The influence that many heard on Black Messiah was likewise traced back to Miles Davis (1926–1991), yet it was not the trumpeter of modern‑jazz lore that surfaced there. Instead, it was the electric Miles of the turn‑of‑the‑’70s—shaped by Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone—whose destructive, chaotic funk reached its apex on On the Corner (1972). Miles’s revolutionary, razor‑edged stance is said to have been catalyzed by his second wife, Betty Davis, whose own albums drew directly on Sly and Hendrix. Their creative partnership faintly echoes the early‑2000s union of D’Angelo and Angie Stone.

After Miles went electric, jazz‑funk records such as Donald Byrd’s Black Byrd (1973) gained traction. Riding that wave into the soul scene—and continuing to intersect with today’s R&B and hip‑hop—is vibraphonist Roy Ayers. Known for a funky, mellow palette, Ayers’s work is heavily sampled and frequently covered; D’Angelo’s take on the 1976 classic “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” is only one example. Erykah Badu, who joined Ayers for a self‑remake of the song, dubbed him “the king of neo‑soul,” and on his 2011 album he even unveiled a track titled “Neo Soul Groove.” Ayers’s impact on neo‑soul is obvious in the records surrounding the Soulquarians. Inspired by that movement, pianist Robert Glasper has labored from the jazz side to restore an R&B feel; his Black Radio series and the trio album Covered (2015)—where he revisits songs by Musiq Soulchild and Bilal—reaffirm how inseparable jazz and R&B can be.

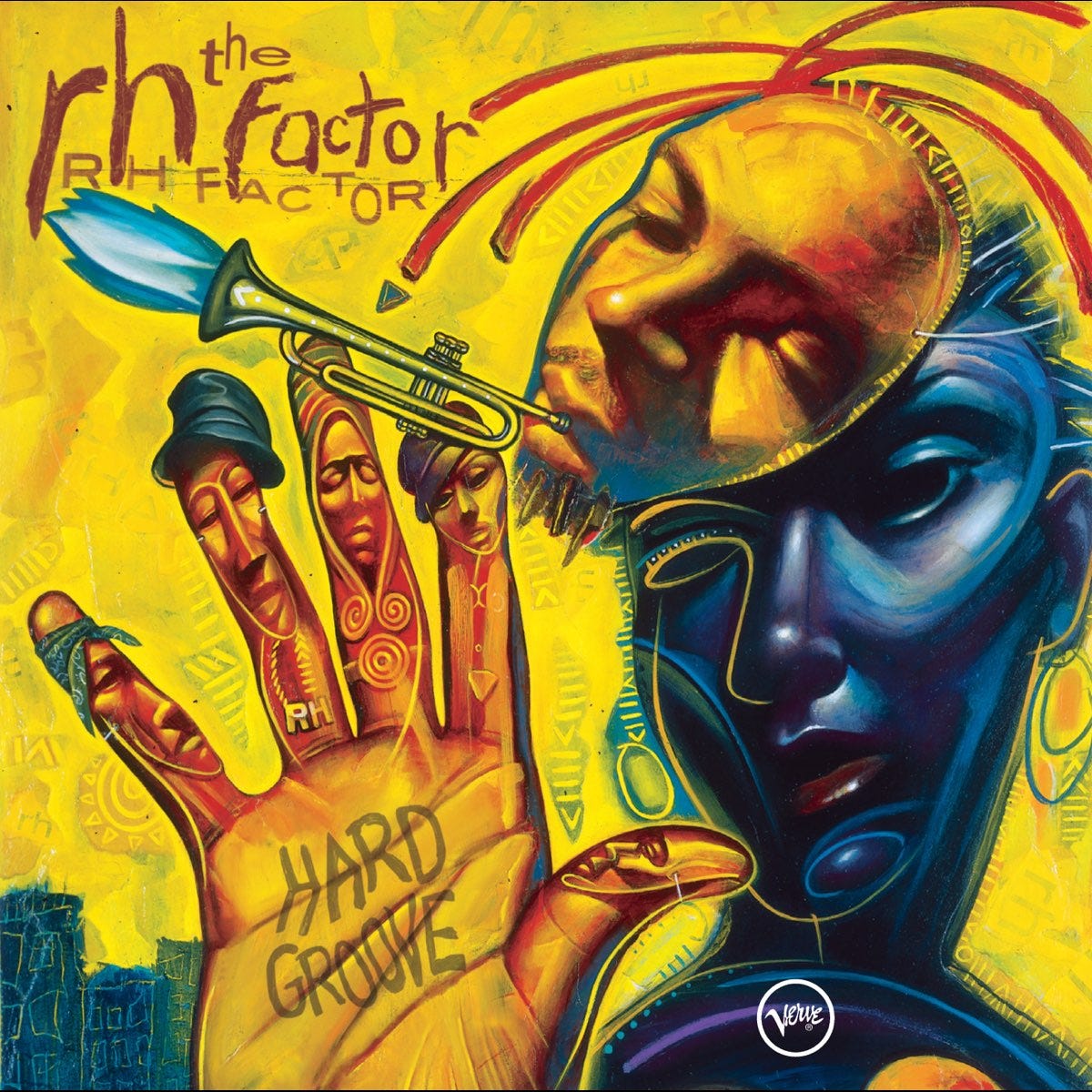

The RH Factor: Hard Groove

In funk and soul, horns have usually meant one of three things: razor‑sharp riffs that trace back to JB‑style funk, lush orchestration aimed at sheer gorgeousness, or wet, emotional saxophone solos. The horns on D’Angelo’s Voodoo, however, are none of these; limited to about two parts, they create tension and release with understated yet unforgettable harmonies. This project was launched by the trumpeter who played those Voodoo parts, Roy Hargrove, who folded fellow Soultronics members like Pino Palladino and James Poyser together with jazz players of his own generation. R&B heads will gravitate to Funkadelic’s “I’ll Stay” sung by D’Angelo, a spit‑flying soul tune fronted by Anthony Hamilton, and the spoken‑word‑style piece by Q‑Tip and Erykah Badu, yet the purely instrumental cuts—never smooth jazz—are just as compelling.

Common and Renée Neufville also appear. — P

Rating: ★★★★½ (4.5/5)

Hargrove’s ensemble marries Voodoo’s lean horn concept to hard‑hitting grooves and top‑tier guests, yielding an instrumental/vocal hybrid that feels essential rather than ornamental.

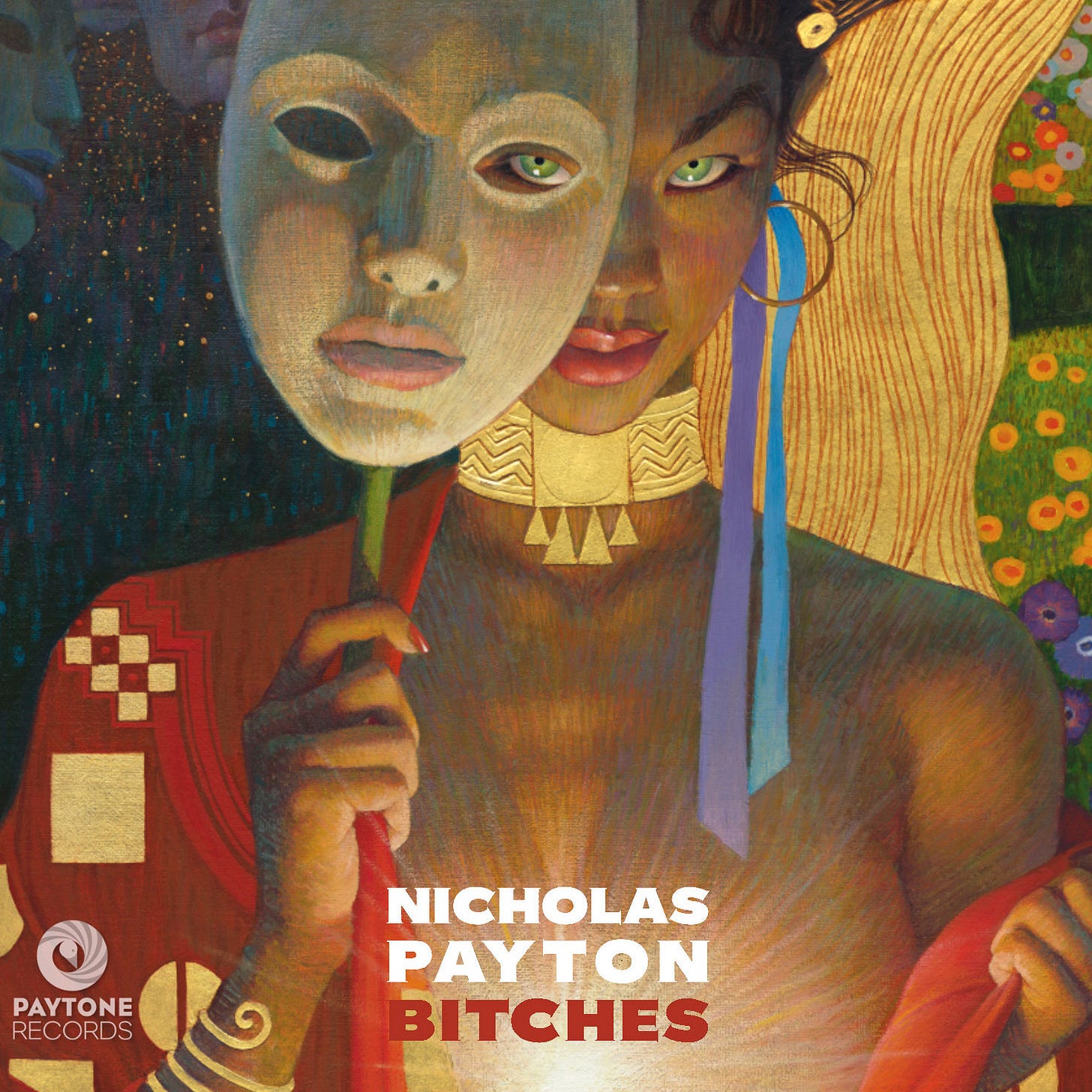

Nicholas Payton: Bitches

A trumpeter from New Orleans, Nicholas Payton has followed Miles Davis’s path from straight‑ahead jazz into electric forms, teaming with hip‑hop and neo‑soul players—Soultronics included on Will Downing sessions—and on this album, he breaks past jazz’s borders with gusto. Doubling as a manifesto for BAM (Black American Music), which calls for both a return to Black musical roots and fresh jazz innovation, the record is an R&B‑leaning vocal set. He enlisted Mark de Clive‑Lowe for assistance and himself handled keyboards, drum machines, and bass; the songs reflect the taste of a listener devoted to Prince, EW&F, D’Angelo, ATCQ, and J Dilla. Guest divas—Esperanza Spalding, Cassandra Wilson, N’Dambi, and China Black—fit perfectly. If you hear neo‑Philly/Soulquarians DNA in “Love and Faith” or “Don’t I Love You Good,” you’re not mistaken. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★½ (4.5/5)

A bold crossover that fuses BAM theory with groove‑centric production; occasional sprawl keeps it shy of classic status, but the ambition lands.

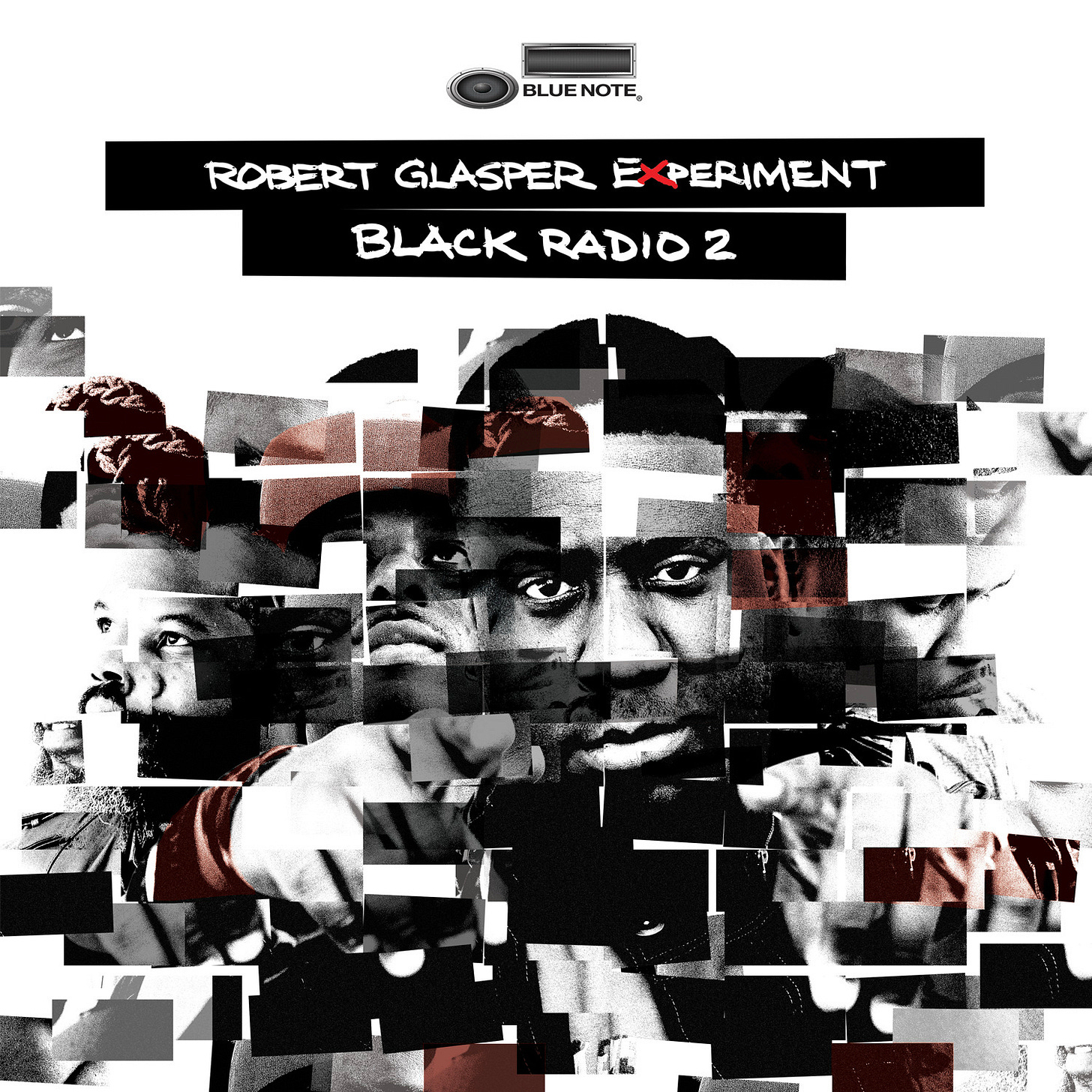

Robert Glasper Experiment: Black Radio 2

A talent that seemed destined to arrive. Programmed early by church music, Robert Glasper pursued the path of a jazz pianist while, through schoolmate Bilal, connecting to hip‑hop circles deeply tied to neo‑soul and absorbing their sensibilities. This second installment of his project binds all those strands together. The singers and Robert co-write most songs. Compatibility with Dwele, Common, Jill Scott, and Anthony Hamilton is a given, but how he makes the unexpected Brandy shine so brightly is astonishing. The band—Robert, Derrick Hodge (b), Casey Benjamin (keys, sax), and Mark Colenburg (ds), who replaced Chris Dave from volume one—plays in a style you could call neo‑soul.

Its victory lies in staying vocalist‑centered and never getting too cerebral. The album’s most exciting track, featuring Norah Jones, explodes with Colenburg’s live drum‑and‑bass beat. — P

Rating: ★★★★½ (4.5/5)

Song‑first focus, daring guest choices, and agile rhythm‑section chemistry elevate this sequel nearly to the level of its landmark predecessor.

Jeff Bradshaw: Bone Deep

Trombone down to the marrow. The Philadelphia trombonist, a session regular with A Touch of Jazz, Jeff Bradshaw, delivers his first leader album—an urban soul‑jazz set mirroring the heyday of neo‑Philly. Nearly half the tracks feature guests: Jill Scott brings the funk on “Slide,” Glenn Lewis croons Stevie Wonder’s “Beyond the Stars,” Carol Riddick floats through the jazzy “Can You Come Over,” and Floetry rides “Beautiful Day,” which quotes the Roots’ “Dynamite!”—each Philly‑centric neo‑soul act matching the husky slide‑tone of Jeff’s horn.

Bilal sounds almost too perfect on the cover of JB’s “Make It Funky,” a homage to mentor Fred Wesley. N’Dambi nails a juke‑joint blues from The Color Purple soundtrack, and Jeff’s own rough‑but‑sweet baritone vocals add flavor. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Guest synergy and trombone charisma capture the neo‑Philly moment, though the breadth of styles keeps it just short of seamless.

Lil John Roberts: The Heartbeat

James Poyser once said, “Philadelphia is full of great drummers,” and he surely meant this one, who joins Pino Palladino on the neo‑soul opener “Space,” trading mics with Eric Roberson, Anthony David, Stokley, and Musiq Soulchild. Jill Scott’s former partner, Lil John Roberts, delivers a debut leader album that mixes live drums and programmed beats while weaving in over twenty guests. Influenced by Black Radio—as Robert Glasper’s cameo confirms—the set lets the late George Duke work a Moog, Ursula Rucker recite poetry, and Nicholas Payton blow trumpet, all revealing the depth of Black music. Snarky Puppy adds Latin‑flavored chops for Kipper Jones to sing Roy Ayers’s “Closer to the Source.” — P

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

Dazzling cameos and sturdy grooves abound, but the sheer guest list challenges cohesion.

Brandon Williams: XII

A Detroit drummer/producer, protégé of Michael J. Powell, and deeply influenced by the late J Dilla, he straddles jazz, R&B, hip‑hop, and techno. For his first leader album, Brandon Williams gathered hometown veterans and neo‑soul singers—from Dennis Coffey (g) to Karriem Riggins (ds)—aiming for a Detroit answer to Robert Glasper Experiment’s Black Radio. The RGE crew appears too: Casey Benjamin’s vocoder colors a slow jam, while Glasper’s Rhodes melts into Jesse Boykins III’s romantic voice. Elsewhere, Frank McComb channels Stevie Wonder, Alex Isley floats over a dreamy slow jam, and Deborah Bond gets passionate on a mid‑groove Amp Fiddler helped write. Tributes to jazz greats round out this large‑scale work. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

A hometown‑proud, genre‑spanning showcase whose reach occasionally exceeds its grasp but delivers abundant highlights.

José James: No Beginning No End

Discovered by Gilles Peterson, José James collaborates freely in club‑music circles, making his first Blue Note set—a reverse‑angle success story compared with the soul artists who had been reaching toward jazz since 2000.

The opener, produced by Pino Palladino with Chris Dave and Robert Glasper, sounds—as that lineup suggests—very close to D’Angelo’s Voodoo. His restrained trumpet lines recall Roy Hargrove and Pino’s in‑the‑pocket bass is again central. Though he cites Billie Holiday and Nat King Cole as vocal influences, the voice that comes to mind first is Gil Scott‑Heron. The album offers quietly soulful singing executed with meticulous control from the duet with Emily King on down. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

A tasteful, Voodoo‑tinged jazz‑soul hybrid whose subtle vocals and airtight band reward close listening.

Gregory Porter: Liquid Spirit

A late bloomer, he drew notice with two Motéma albums and, in barely three years, joined the top tier of jazz singers. Blessed with a warm, fervent baritone, he sings bittersweet love songs but also protest numbers like “1960 What?” (linking modern times to Detroit’s 1967 uprising), prefiguring what D’Angelo later tried on Black Messiah. The roots—his mother, a pastor, influences Donny Hathaway and Marvin Gaye—echo D’Angelo’s, and tying his debut Waterto “water” mirrors D’Angelo’s symbolism. On this Blue Note album, he dedicates “When Love Was King” to Dr. King, gives voice to society’s downtrodden on “Free,” and, with covers such as Ramsey Lewis Trio’s “The In Crowd” and Max Roach’s “Lonesome Lover,” keeps blues feeling alive throughout. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★½ (4.5/5)

Blues‑soaked protest and romance, delivered in a commanding baritone, make this his definitive statement.

Esperanza Spalding: Radio Music Society

Esperanza Spalding is the prodigy bassist who became the first jazz artist ever to win the Best New Artist Grammy. Having started singing as a teen in the noise‑folk outfit Mysterious Ways, Esperanza had already sung on leader dates; here, she switches from upright to electric bass on many tracks and, true to the title, makes every cut a vocal tune that could waft from a tasteful radio.

The originals stand shoulder‑to‑shoulder with the most intellectually thrilling cover of Michael Jackson’s “Can’t Help It” you’ve ever heard. Perhaps because singers trained in scat‑dominating pedagogy can’t rely on pure vocal acrobatics, the melodies are carefully crafted; combined with the interplay among trusted musicians and her clear timbre, the feel recalls Patrice Rushen in the ‘70s. The brainy arrangements rival Steely Dan, and though the details are murky, Q‑Tip is also listed among the producers. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★★★ (5/5)

High‑concept pop‑jazz executed with dazzling musicianship.

Brian Culbertson: Bringing Back the Funk

A multi‑instrumentalist with fourteen leader albums in smooth jazz, he loves featuring R&B singers and often mingles with funk players—he once even toured Japan with Rufus. This is one of his funkiest sets with Maurice White as executive producer. Right out of the gate, he drafts Bootsy Collins to juice up a P‑funk opener, hands the mic to Musiq Soulchild for a lightly electrified take on Kool & The Gang’s “Hollywood Swinging,” and turns Tower of Power’s “You Got to Funkifize” into a church‑revival blowout—one live‑band groove after another from veteran funkateers. Some tidy, smooth‑jazz instrumentals co‑written with Larry Dunn may split opinions, but even if that side isn’t your thing, don’t miss Ledisi’s fiery take on Bill Withers’s “The World Keeps Going Around.” — P

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

A party‑ready funk detour that thrills when the veterans cut loose, though the polished instrumentals break momentum.

The Foreign Exchange: Love In Flying Colors

Dutch beat‑maker Nicolay and former Little Brother MC Phonte form this R&B unit: The Foreign Exchange. Their fourth studio album, with Phonte now primarily a singer, is not jazz, yet on tracks like “I Knew Then” with Carmen Rogers or “Better” featuring Eric Roberson, it overflows with the “sky‑high” openness of Donald Byrd or Bobbi Humphrey records produced by the Mizell Brothers in the ‘70s, unfolding a modern neo‑soul rooted in jazz‑funk craft.

There are also ‘80s‑black‑contemporary machine‑beat numbers, Nicolay’s specialty, such as “Right After Midnight” with Sy Smith or “Dreams Are Made for Two” sung by Carlitta Durand, all delivered with their trademark organic warmth. Collective keyboardist Zo! also joins, making the album radiate Soulquarians‑style collective spirit. — P

Rating: ★★★★☆ (4/5)

Vintage jazz‑funk lift and ‘80s machine soul blend seamlessly, proving the duo’s evolution from backpack rap to sophisticated groove unit.

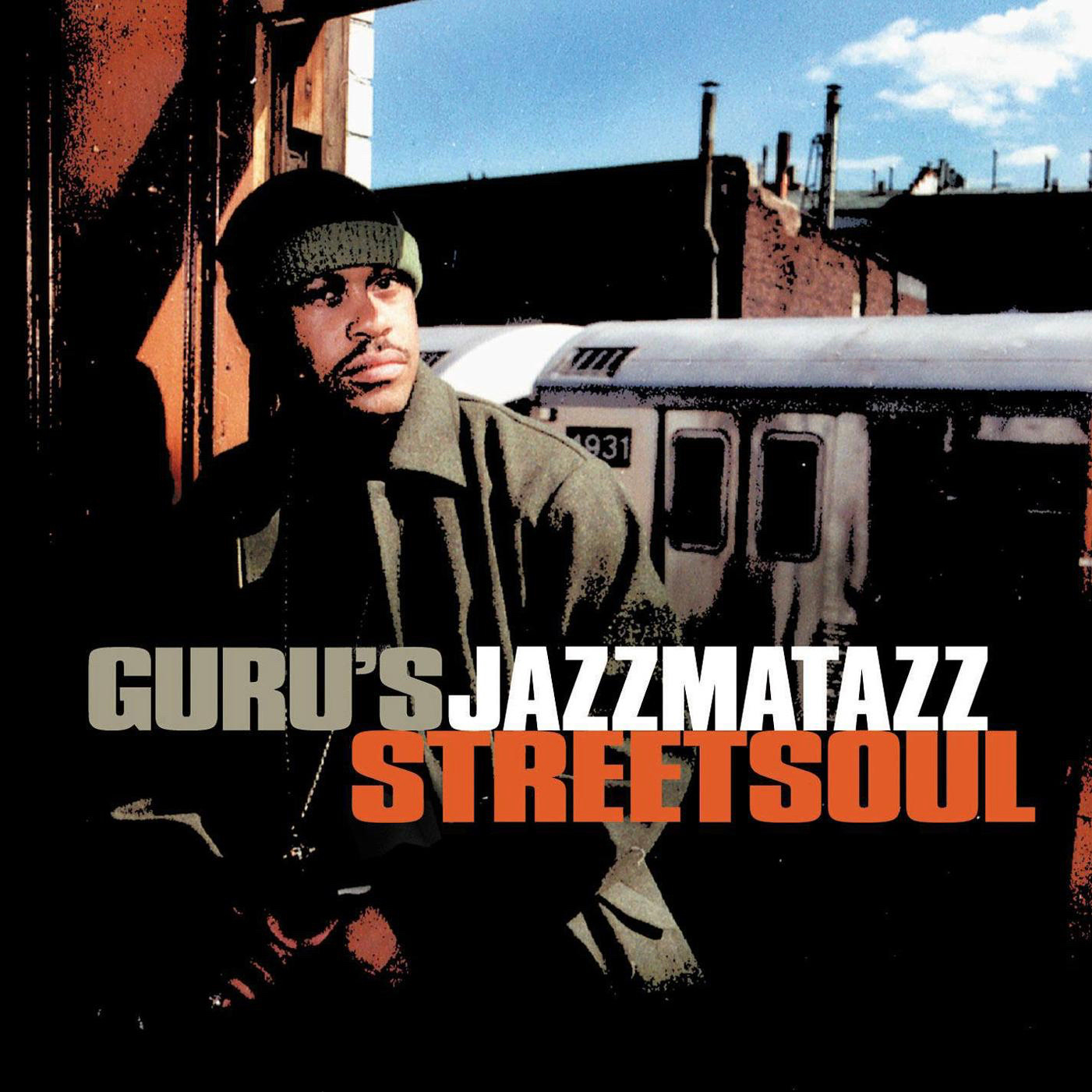

Guru: Jazzmatazz — Streetsoul

Guru of Gang Starr was an early practitioner of linking hip‑hop, soul, and jazz via Jazzmatazz. The first two volumes laid rap over hip‑hop beats, live jazz, and soul vocals—think DJ Premier tracks laced with Chaka Khan and Branford Marsalis sax. By this third set, most cuts find rap riding over neo‑soul, yet perhaps it hints that post‑D’Angelo R&B—which now eagerly imports jazz elements—owes a quiet debt to Jazzmatazz. Important players who would later dominate—Erykah Badu bringing her own color with her crew in tow, Bilal, the Roots, Angie Stone—show up en masse. Donell Jones pairs surprisingly well with Premier’s groove, and Isaac Hayes still stuns with the same gravitas he had in the ‘70s. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

Though less groundbreaking than the first two volumes, it remains a valuable bridge between golden‑age rap and the neo‑soul wave it helped inspire.

New Classic Soul / Organic Soul / Neo‑Soul

(By Imani Raven)

Anyone who remembers the early music of D’Angelo, Maxwell, and Tony! Toni! Toné! was once labeled “new classic soul” is, by now, a veteran listener. Printed in the hinge of D’Angelo’s 1995 debut CD, the term suggested a new “classic” soul created by the hip‑hop generation in response to a ’70s soul revival. Although it saw limited use in the United States, the phrase gained modest currency in the U.K.—where a compilation literally titled Nu Classic Soul appeared—and even wider acceptance in Japan.

Erykah Badu was likewise grouped with the new‑classic cohort. When the U.K. compilation series Organic Soul appeared in the early 2000s—spotlighting indie singers such as YahZarah, Ndambi, and Ledisi—the term “organic soul” began circulating, chiefly in Britain and Japan, to describe music of that stripe.

Meanwhile, in America—the soul motherland—Motown president Kedar Massenburg, who discovered D’Angelo and Badu, popularized the banners “neo‑classic soul” and, more enduringly, “neo‑soul” while launching Chico DeBarge and Glenn Lewis. The words soon became global currency. They were not Massenburg’s coinage, though; as early as 1987 a Washington Post writer had called Force M.D.’s “Touch and Go” “a fine piece of neo‑soul,” and scattered usages existed elsewhere. Massenburg merely formalized an intuitive journalistic descriptor into a defined style.

Neo‑soul spread just as he intended. By around 2000, it referred to a run of R&B artists—Alicia Keys, Jill Scott, Bilal, and others—whose jazzy, mellow sound was molded under East‑Coast hip‑hop’s influence. Those hailing from Philadelphia were dubbed “neo‑Philly” in homage to the city’s classic soul heritage. Before long, the market overflowed with music sporting the neo‑soul tag.

Some artists bristled at the term’s marketing slant or the discontinuity implied by the prefix “neo.” Badu engraved “NEO SOUL IS DEAD” on the cover of Worldwide Underground, and Jaguar Wright titled her second album Divorcing Neo 2 Marry Soul. Whether or not their protests swayed the scene, the overheated neo‑soul/neo‑Philly boom cooled by the mid‑2000s—only to show signs of rekindling in recent years. The rising visibility of live musicians hints that one spark was the surge of jazz‑side approaches by players such as Robert Glasper and José James.

When the ascendance of D’Angelo and his peers first caught attention, Jam & Lewis praised the movement as “the rebirth of real voices and real musicianship.” Whatever the label, music of that caliber is welcome in any era.

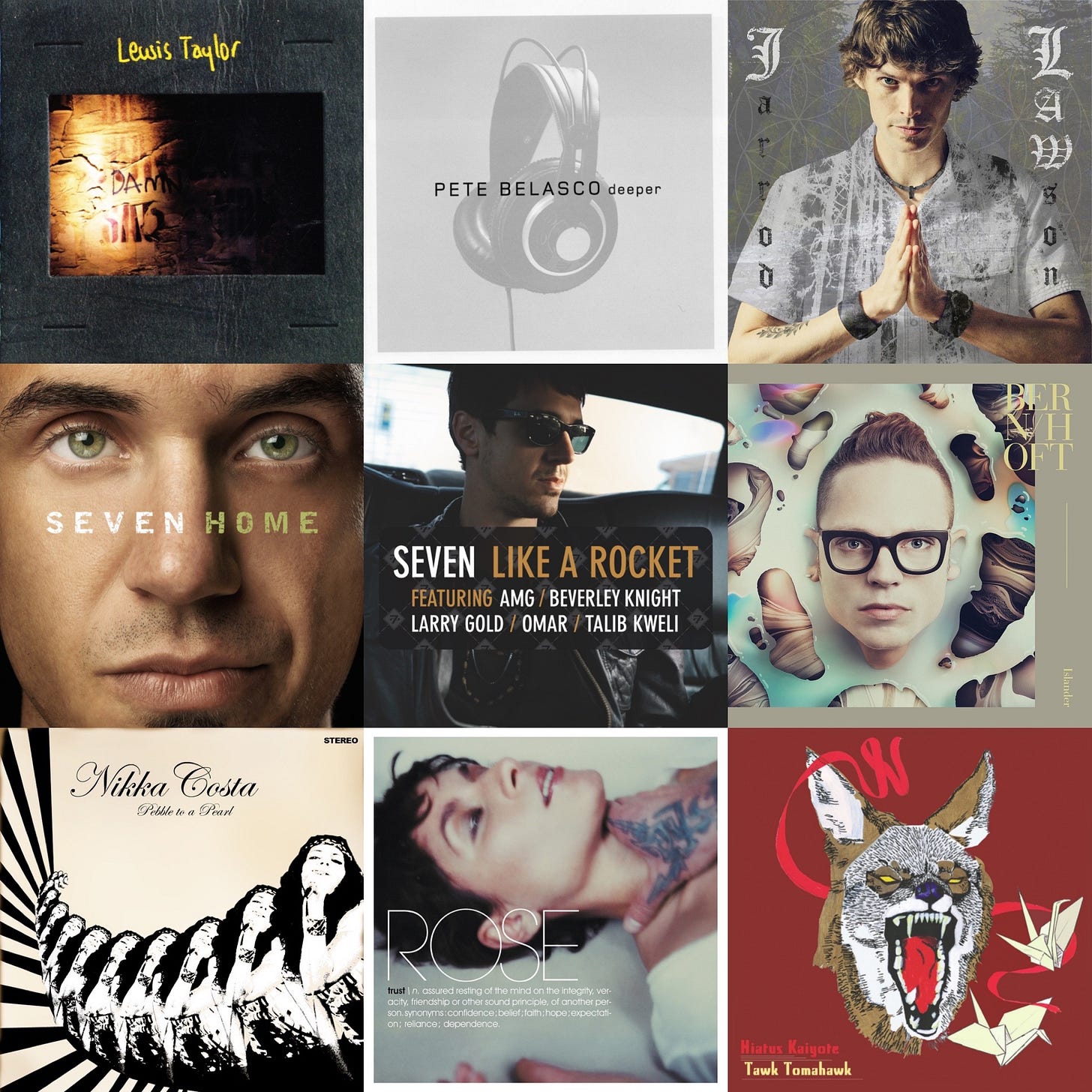

Blue‑Eyed Soul in the Lineage of D’Angelo

(By Tai Lawson)

“Blue‑eyed soul” once denoted acts from the Righteous Brothers to Hall & Oates, and more recently Sam Smith—white artists performing soul music. Definitions vary, and most rock or pop could qualify if “R&B‑flavored” alone sufficed. Commonly, though, the category includes singers launched directly into the R&B market (Teena Marie, Robin Thicke), those entwined with R&B circles (Justin Timberlake, Amy Winehouse), and performers who have assimilated Black music (Lisa Stansfield, Mayer Hawthorne).

Among those inheriting D’Angelo’s mantle yet omitted from the accompanying disc guide, the first is U.K. multi‑instrumentalist Lewis Taylor. A missing link between Marvin Gaye and David Bowie, his self‑titled 1996 album is regarded, alongside Brown Sugar, as a pioneering neo‑soul work; Anthony Hamilton’s cover of “Betterlove” attests to its stature. In the post‑boom era, indie artist Pete Belasco—an underground counterpart to Remy Shand—delivered fine sets such as Deeper (2004) and Lights On (2012), which play like Maxwell interpreted through smooth jazz. From Portland, Oregon, Jarrod Lawson—deeply influenced by Stevie Wonder and trained in jazz and Christian music—offered a self‑titled 2014 debut hailed as neo‑soul’s savior; onstage he even sings D’Angelo’s “One Mo’ Gin.” Add Vancouver newcomer David Morin and the rock‑ and folk‑tinged Allen Stone to the list.

Artists who have collaborated with neo‑soul acts on record include Swiss falsetto stylist Seven, dubbed “the Swiss Robin Thicke.” On Home (2007) he enlisted Rahsaan Patterson and James Poyser and duetted with Conya Doss; Like a Rocket (2009) paired him with Omar and Talib Kweli. Norwegian singer‑songwriter Jarle Bernhoft achieved the rare feat of becoming the first non‑American white artist nominated for a Grammy in the Best R&B Album category; his Islander (2014) features the Jill Scott duet “No Us, No Them.”

Among women, beyond Joss Stone stands Nikka Costa, whose two Virgin albums employed Questlove and James Poyser; Pebble to a Pearl (2008) on Stax again teamed her with Poyser and included a Johnny “Guitar” Watson cover, resonating with D’Angelo’s aesthetic. Dutch singer Rose’s Trust (2002), produced with Poyser and King Britt, offered a Philly‑styled organic soul. Though a band, Australian outfit Hiatus Kaiyote—whose jazzy‑soul track “Nakamarra” (2012) gained notice in its original and Q‑Tip‑featuring versions—also displays a keen neo‑soul consciousness.

Gospel After D’Angelo

(By Brandon O’Sullivan)

D’Angelo’s arrival also rippled through gospel. Here is a brief survey of gospel that shares kinship with him and with neo‑soul. Montrell Darrett, formerly of Commissioned, issued Chronicles of the Soul (1999), whose Ohio Players‑ or Sly‑tinged funk and layered vocals are overtly D’Angelo‑esque. Darrett and neo‑soul stalwart Kelvin Wooten co‑produced Shawn Simmons’s True Story (2006) in a similar vein.

Moving a bit away from D’Angelo yet still within neo‑Philly territory, Ty Tribbett & G.A.’s Life (2004) employed many of the musicians backing that scene. The mixed‑gender unit Spiritual Pieces released two albums on Tommy Boy, including the neo‑soul‑leaning Soul Food (2000); member Phonz’s solo set Still Alive (2003) follows suit. Marvin Winans teamed with Tommy Sims for Alone But Not Alone (2007), effectively an extension of Sims’s own solo world. Dewayne Woods’s Life Lessons (2015) heightened its neo‑soul color by featuring Avery Sunshine and Anthony Hamilton.

Among acoustic‑guitar‑driven projects, note How U Gonna Live (2000) by The Word—brothers Chris and Tony Rich, the latter handling full production—plus Antonio Neal’s pop‑oriented Days of My Life (2005) and Leon Timbo’s debut Soul Sessions (2005), a guitar‑and‑voice effort from an artist still striving for a breakthrough.

Female singers have kept pace. Lisa McClendon, a flagship neo‑soul gospel voice who debuted on the same label as Leon, delivered Soul Music (2003) with vocals reminiscent of Lauryn Hill. Trin-i-tee 5:7 alumna Trinisa McClendon drew buzz when Kanye West produced one track on Overtones & Innuendos (2006). Cynthia Jones, long prominent in gospel jazz, re‑entered the spotlight via Ben Tankard’s Full Tank (2012) and offered Journey of Soul (2011). From the Tri‑City Singers, LaJuene Thompson’s first solo album, Soul Inspiration (2001), is another standout. The pinnacle may be More of You (2004) by Sunny Hawkins—fully supported by her husband, former R&B singer‑producer Jamie Hawkins.

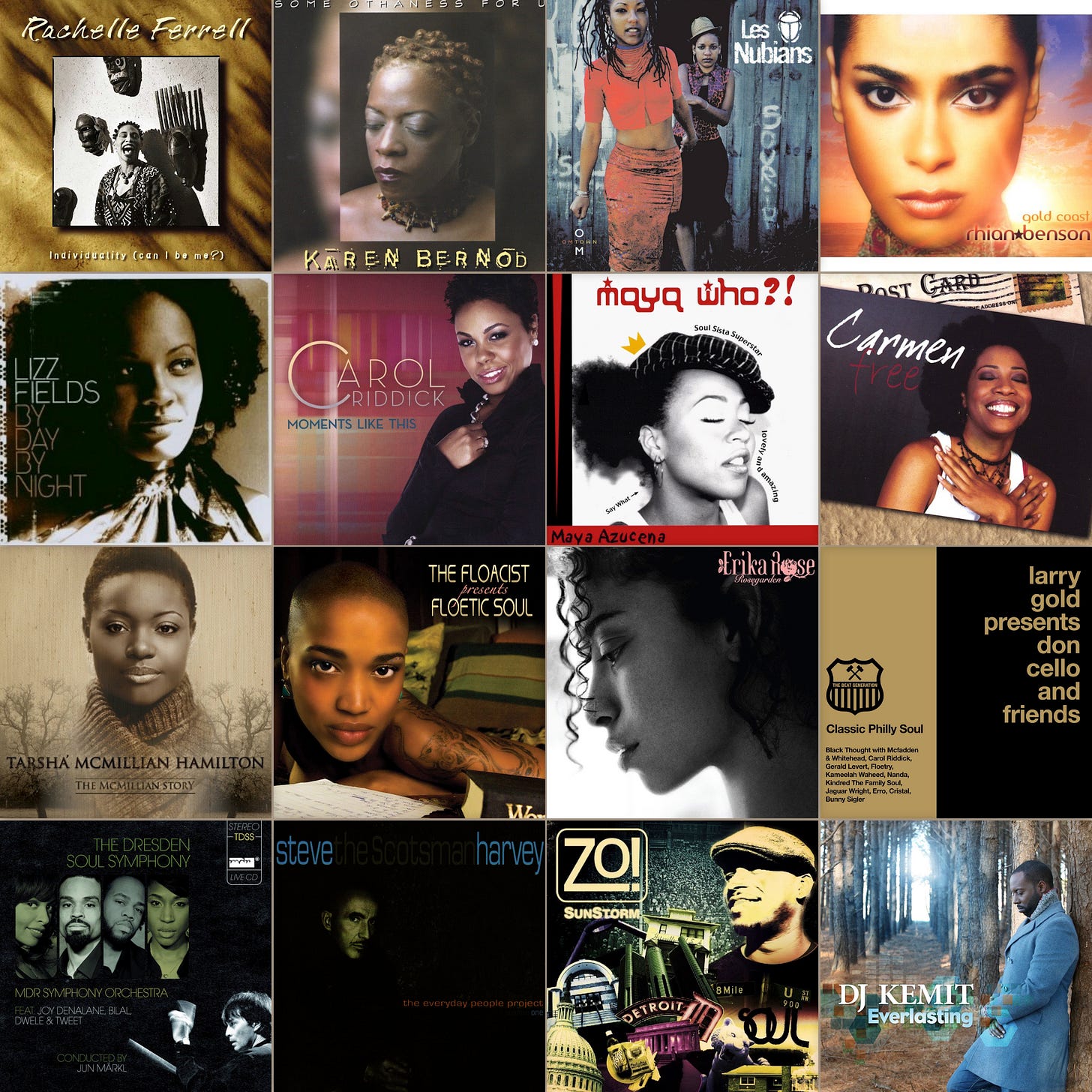

The Narrow Road Into the Depths of Neo‑Soul

(By Phil)

Neo‑soul appears frequently in this guide. Even so, only a fraction of the relevant material could be included, and when I set out to follow up on the artists and recordings that slipped through the cracks, I discovered that the overwhelming majority were female singers. Around the year 2000 a steady stream of post‑Erykah gems was being released, such as the prodigy Rachelle Ferrell’s Individuality (Can I Be Me?) and Karen Bernod’s Some Othaness For U—Bernod had sung background on live dates for D’Angelo and Erykah Badu—both issued in 2000. From outside the United States came projects that approached neo‑soul along the Sade line, including the French sister duo Les Nubians’Princesses Nubiennes (1998) and Gold Coast (2003) by Ghana‑born Rhian Benson, created in collaboration with James Poyser and Bob Power.

From Philadelphia, the epicenter of neo‑soul, good releases also kept arriving. Chief among them are Liz Fields’ …By Day By Night… (2003), produced by Damon Bennett (keyboards, etc.), and Carol Riddick’sMoments Like This (2006), created with James Poyser and Ivan & Carvin—both should be remembered as hidden classics of neo‑Philly. Among New York songstresses, Maya Azucena’s debut, Maya Who? (2003), in which she belts over live‑band grooves, is outstanding. From the South, organic albums such as Dallas native Carmen Rogers’ debut Free (2004) and the gospel set The McMilian Story (2008) by Tasha McMilian‑Hamilton, wife of Anthony Hamilton. Natalie Stewart of Floetry, recording under the name The Floacist, issued several albums; in particular, The Floacist Presents Floetic Soul (2010), featuring Raheem DeVaughn, Musiq Soulchild, and Lalah Hathaway, embodied her affirmative take on the neo‑soul genre. Others left out this time include Allison Crockett, Erika Rose, Wayna, Muhsinah, and Chocolate.

Turning to projects by producers… At the height of neo‑Philly in 2003, cellist Larry Gold—formerly of MFSB and the Salsoul Orchestra—released Larry Gold Presents Don Cello and Friends on the U.K. label BBE, a superb concept that seated veteran and new Philadelphia singers side by side, the kind of undertaking only the godfather of neo‑Philly could mount. Gold also wrote the scores for The Dresden Soul Symphony (2008, also on DVD), a live recording in which Joy Denalane, Bilal, Dwele, and Tweet, backed by a renowned German orchestra, performed soul classics from the ’60s and ’70s; this too was a product of the neo‑Philly boom. Other releases not to be forgotten as invitations to bona‑fide neo‑soul acts include The Everyday People Project Vol. 11 (2006) by U.K. figure Steve “Scotsman” Hanvey, SunStorm (2010) by current Foreign Exchange keyboardist Zo!, and Everlasting (2012) by DJ Kemit.