The Handguide to the Ladies of Hip-Hop

Presented chronologically to show the long march of ladies in rap music toward success and recognition, contains several types of projects.

The following selection, presented chronologically to show the long march of ladies in rap music toward success and recognition, contains several types of projects. Some, close to perfection, are classics, milestones of rap. Others, on the contrary, open themselves up to criticism. They remain good albums (or mixtapes) that count in the history of rap or that, while confidential, represent the various directions taken by women in the cruel world of hip-hop.

Also, this selection sometimes broadens the horizon to reflect the diversity of women’s rap best. One of the women honored here is not a rapper but a DJ (Shortee), and two others distinguish themselves in the neighboring discipline of spoken poetry (Ursula Rucker, Kae Tempest). Likewise, some of the groups mentioned are not composed solely of women (Funky 4 + 1, Digable Planets, Crime Mob); another devotes itself to a different genre from rap (TLC). All of them, however, had at least one female rapper who left her mark on the history of this music. In fact, it would be impossible to talk about the women who have mattered in rap without dwelling on such major figures as Sha-Rock, Left Eye, Ladybug Mecca, or Diamond and Princess.

Lastly, we want to commemorate the albums, mixtapes, and EPs that aren’t given a full breakdown in the main guide but deserve a mention:

Sparky D, This Is Sparky D’s World

Finesse & Synquis, Soul Sisters

Sweet Tee, It’s Tee Time

The Real Roxanne, The Real Roxanne

Oaktown 357, Wild & Loose

Antoinette, Who’s the Boss?

Big Lady K, Bigger Than Life

Tairrie B, Power of a Woman

H.W.A., Livin’ In a Hoe House

Monie Love, Down to Earth

Shazzy, Attitude: A Hip Hop Rapsody

Nikki D, Daddy’s Little Girl

Medusa, Feline Science

N-Tyce, Antidote

Sylk-E. Fyne, Raw Sylk

Mercedes, Rear End

Solé, Skin Deep

Amil, All Money Is Legal (A.M.I.L.)

Doggy’s Angels, Pleezbaleevit!

Mocha, Bella Mafia

Angie Martinez, Up Close and Personal

Shaunta, Shaunta

Ms. Dynamite, A Little Deeper

Vita, La Dolce Vita

Apani B Fly, Story 2 Tell

Psalm One, The Death of Frequent Flyer

Lady Sovereign, Public Warning

Rita J, Artist Workshop

Tiye Phoenix, Half Woman Half Amazin’

Speech Debelle, Speech Therapy

Boog Brown & Apollo Brown, Brown Study

Kreayshawn, Something ‘Bout Kreay

Yugen Blakrok, Return of the Astro-Goth

Nitty Scott, The Art of Chill

Tiff The Gift, Better to Give

Tink, Winter’s Diary 3

Omeretta the Great, Black Magic: A Dose of Reality

Saweetie, High Maintenance (EP)

Queen Key, Eat My Pussy (EP)

Bhad Bhabie, 15

Baby Tate, Girls

DreamDoll, Life In Plastic 2

Haviah Mighty, 13th Floor

Deetranada, DEEvsEVERYBODY!

Nappy Nina, Dumb Doubt (EP)

Kash Doll, Stacked

Neelam, Different (EP)

Mother Nature, Portalz (EP)

Lyric Jones, Closer Than They Appear (EP)

BIA, For Certain (EP)

Lakeyah, Time’s Up (EP)

Rubi Rose, For the Streets (EP)

Stunna Girl, Stunna This Stunna That

7xvethegenius, Self 7xve 2 (EP)

ENNY, Under Twenty Five (EP)

Kaliii, Toxic Chocolate (EP)

OSHUN, vol. ii

Sol ChYld, Something Came to Me (EP)

Chyna Streetz & 183rd, From Hell to Chanel

Santana Fox, Eye Candy

Anycia, Princess Pop That

Jourden, Straight, No Chase (EP)

Monaleo, Throwing Bows (EP)

Samara Cyn, The Drive Home (EP)

BalakeIANA, Back In the Field

Queen Herawin, Awaken the Sleeping Giant

ANTHOLOGY OF WOMEN IN HIP-HOP

Also, if you want to read the rest of the series, please check them out here:

The Mother of Hip-Hop

In the eyes of many, rap has a problem with women. Its main players—whether we speak of its stars, its activists, or its fans—are overwhelmingly men. In both its lyrics and its imagery, it has a reputation for being dreadfully misogynistic and for portraying women only in the degrading form …

Misogyny On the Mic

In France as well, in the manner of Sylvia Robinson, women are at the forefront. They are often even more visionary and daring than men. The first example comes from Laurence Touitou. A very young architect in the early eighties, she flew off to New York, where she met LL Cool J as a teenager. On her return to the country, she was the originator of the …

The Era of Bad Bitches

Despite their bitter rivalry—one of the longest-lasting in rap history—Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown share many essential traits. Initially friends (they collaborated with Da Brat on a remix of “No One Else” by the R&B group Total, and they had even planned a joint album,

I Came to Save a Thing Called Female Rap

At the end of the 2000s, this protégé of the rapper of the moment, Lil Wayne, began making a name for herself on mixtapes as a street-savvy mic specialist. In 2010, she astonished audiences with her striking verbal virtuosity on the colossal track “Monster,” where her incredible verse overshadowed even JAY-Z and Rick Ross—major rap stars also featured o…

Funky 4+1, That’s the Joint

Contrary to what many people think, Sha-Rock was not immediately the “+1” of her group. Originally, she was fully part of the Funky Four. It was only later, after she left the group, was replaced, and then returned, that they all adopted that original name. In truth, Sharon Green does not seek to put herself forward. She speaks on the same level as the boys, using roughly the same amount of airtime. At least, that is what we hear on this compilation, which, in 2000, brought together all the singles of a group that never had the opportunity to release a proper album. On these long, playful, festive tracks meant for dancing—so typical of the early days of rap, with their “real” instruments and their looting of soul, funk, or disco tracks (“That’s the Joint” is inspired by “Rescue Me” by a Taste of Honey, while “Rappin’ and Rockin’ yhe House” is influenced by “Got to Be Real” by Cheryl Lynn, and “King Heroin” reuses “The Apprentice” by The O’Jays)—Sharon Green holds her place. Still, her feminine voice stands out, giving the group a decisive distinguishing feature. With her, the Funky 4 + 1 were among the great pioneers of the hip-hop epic. They were the first rappers to sign a record deal, recording for Enjoy before joining Sugarhill Records.

At more than 15 minutes long (even longer than “Rapper’s Delight”), their first single, “Rappin and Rocking the House,” remained for a long time the longest rap song ever made. Their reference track, “That’s the Joint,” is generally considered one of the very best from the early days of hip-hop. And above all, on Valentine’s Day 1981, by appearing on Saturday Night Live at the invitation of Debbie Harry of Blondie, this quintet composed of teenagers from the Bronx became the first to bring rap to American national television screens. That night, however, Sha-Rock was already facing one of the great constraints of any female rapper’s career: pregnant, she was suffering from nausea, which made her male companions nervous. And indeed, their shared adventure did not last. Two years later, the group split up, and its members were scattered among various projects: US Girls for Sha-Rock (a trio with Lisa Lee and Debbie Dee), Double Trouble for Lil’ Rodney Cee and K.K. Rockwell, and a solo career for Jazzy Jeff—the only one to enjoy relative success with “King Heroin” in 1985. Later on, only aficionados remembered the Funky 4 + 1 and Sha-Rock, the first great female rapper in history.

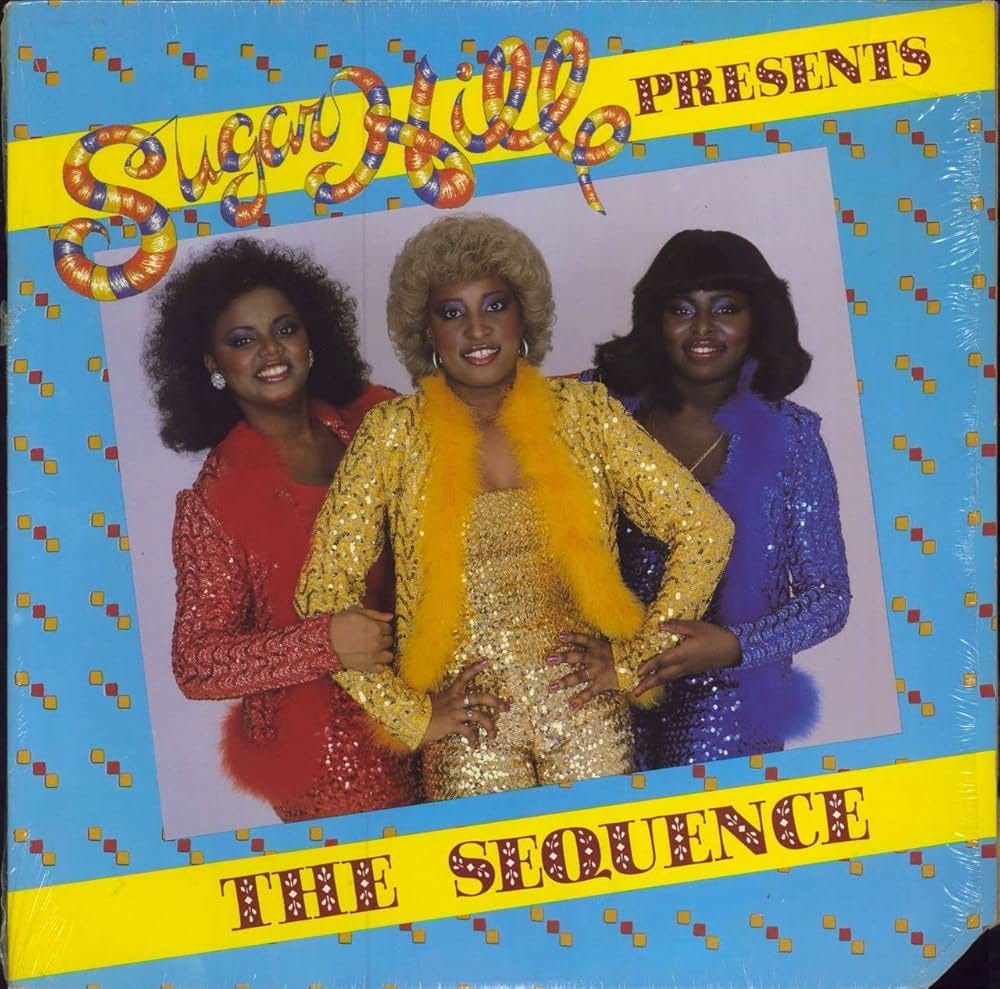

The Sequence, Sugarhill Presents The Sequence

The story of The Sequence strongly contradicts those who think women’s place in hip-hop has always been marginal. Indeed, these three female rappers released the second single released by Sugar Hill Records after “Rapper’s Delight”—the track that popularized the genre. And this track, “Funk You Up,” is anything but trivial. Released as early as 1979 by three friends from South Carolina, who discovered their calling after hearing Sugarhill Gang, it was another hit. A classic of early rap, it was later sampled by some (most notably Dr. Dre) or even pillaged by others. Furthermore, the trio formed by Cheryl Cook (The Pearl), Gwendolyn Chisolm (Blondy), and Angela Brown (Angie B) enjoyed a certain longevity. The Sequence released three albums and other notable singles, including “Monster Jam” with Spoonie Gee, and they again found success in 1982 with the ballad “I Don’t Need Your Love.” And one of its members, Angie B—who would be seen alongside Prince, Lenny Kravitz, and D’Angelo—tasted fame around the year 2000 in the guise of the neo-soul singer Angie Stone. That future in traditional African-American music was predictable upon hearing their first album.

Like most rap albums of the time, it featured tracks still rooted in soul, funk, and disco—be it the syrupy romance “The Times We’re Alone” or their second single, “Funky Sound (Tear the Roof Off),” which was a reinterpretation of “Give Up the Funk (Tear the Roof Off the Sucker)” by Parliament. As for “Simon Says,” “We Don’t Rap the Rap,” and “And You Know That,” though they were indeed rapped, they were nevertheless backed by instruments also drawn from funk. With The Sequence, as elsewhere on Sugar Hill Records, rap was not yet seen or practiced as a genre in itself, but rather as a means of warming up and motivating listeners—just as it had been in the block parties and nightclubs that witnessed its birth. This resulted in long tracks whose lyrics, made up of stock phrases chanted in chorus and interspersed with shouts or whistles, were above all playful invitations to dance. This first album, which critically lacked the single “Funk You Up” (despite the visionary presence of the word “gangsta” on the track “And You Know That”), proved unremarkable and generic, explaining in part why, a few decades later, The Sequence is among the forgotten names of the great saga of female rap.

Also check out: The Sequence (1982)

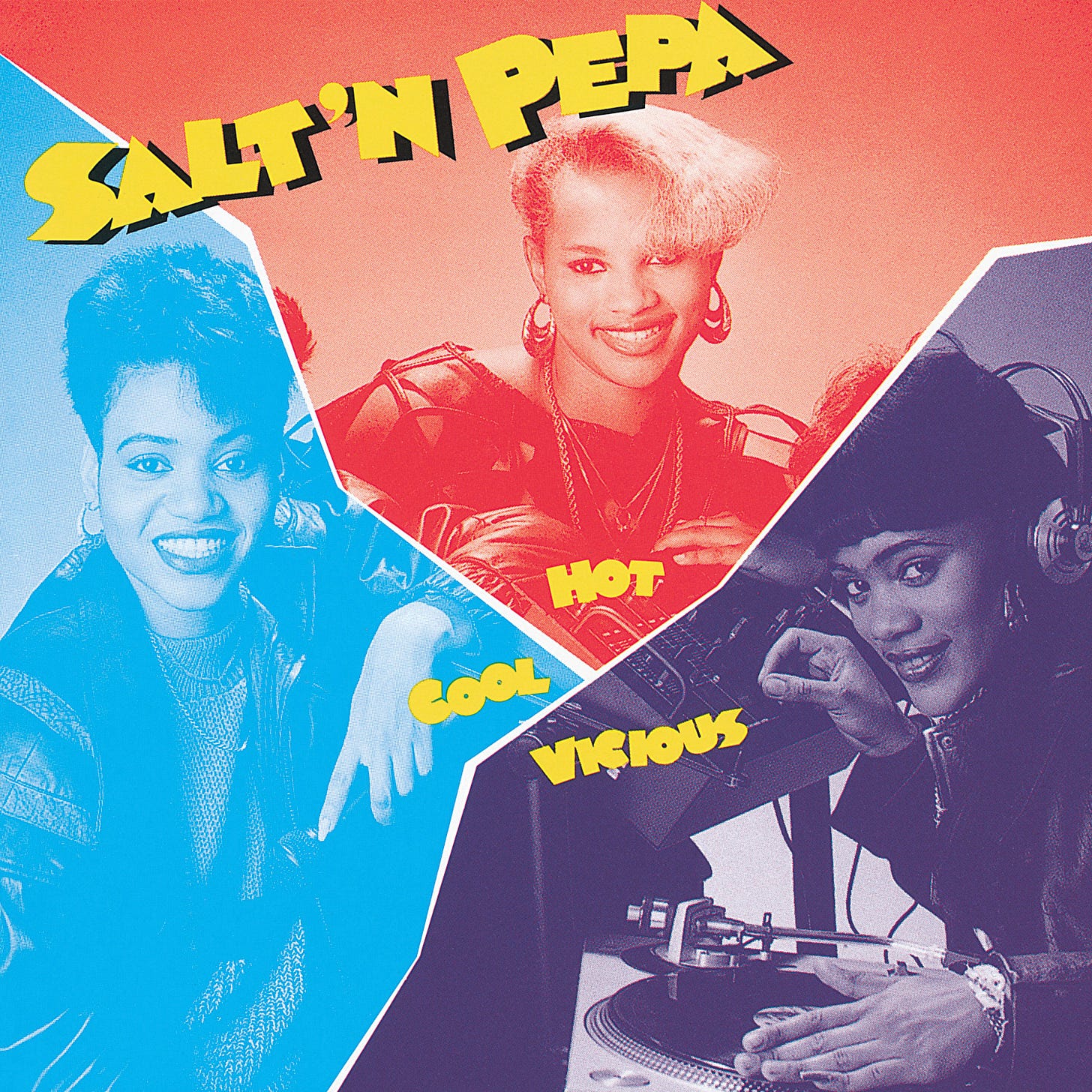

Salt-N-Pepa, Hot, Cool, & Vicious

The first stars of female hip-hop were Salt (Cheryl James), Pepa (Sandra Denton), and their DJ Spinderella (Deidra Roper). They gave hip-hop its first platinum album by women with Hot, Cool & Vicious, then pursued a successful career. However, upon closer examination, this record was not entirely a women’s affair. Spinderella, who arrived late, did not actually contribute anything to the music: she simply posed on the cover. Hurby Azor, who was then dating Salt and managing the trio, produced the record and wrote a large portion of its lyrics. And it was thanks to another man, the California DJ Cameron Paul, that the trio experienced success. Before him, indeed, the former Super Nature had already made a name for themselves in hip-hop circles with a track, “The Show Stoppa,” which responded to “The Show” by Doug E. Fresh and Slick Rick. But by efficiently remixing their track “Push It” (originally just a B-side), Cameron Paul brought them to the general public’s attention, paving the way for the considerable success of this first album several months after its release.

That album, however, did not change the scene in the rap of that time. The trio appeared to be the female counterpart to Run-D.M.C., sharing many of their features: apart from the presence of two MCs and a DJ, their music was lively and minimalist, focusing mainly on ego-tripping, and Salt and Pepa, like their male peers, often finished each other’s lines. The chief novelty of this first album lay in the position taken by its performers: unlike other female rappers, they played up their attractive looks and sex appeal. In a number of tracks (“Tramp,” “The Show Stoppa,” “Chick On the Side,” “I’ll Take Your Man”), they presented themselves as assertive women who took control of their love and sex lives, reversing the usual sexist clichés by treating their lovers like objects. A few years later, they continued in this vein with the hit “Let’s Talk About Sex,” in which they demanded a female perspective on the tricky subject of sexuality. Of course, they still offered a playful take on female rap, far from the vibe of Lil’ Kim or Foxy Brown. But even with the very title of this first album, Hot, Cool & Vicious (“hot, cool, and vicious”), a new mindset had already arrived, announcing the approach many female rappers would embrace in the future.

Also check out: Blacks’ Magic (1990), Very Necessary (1993)

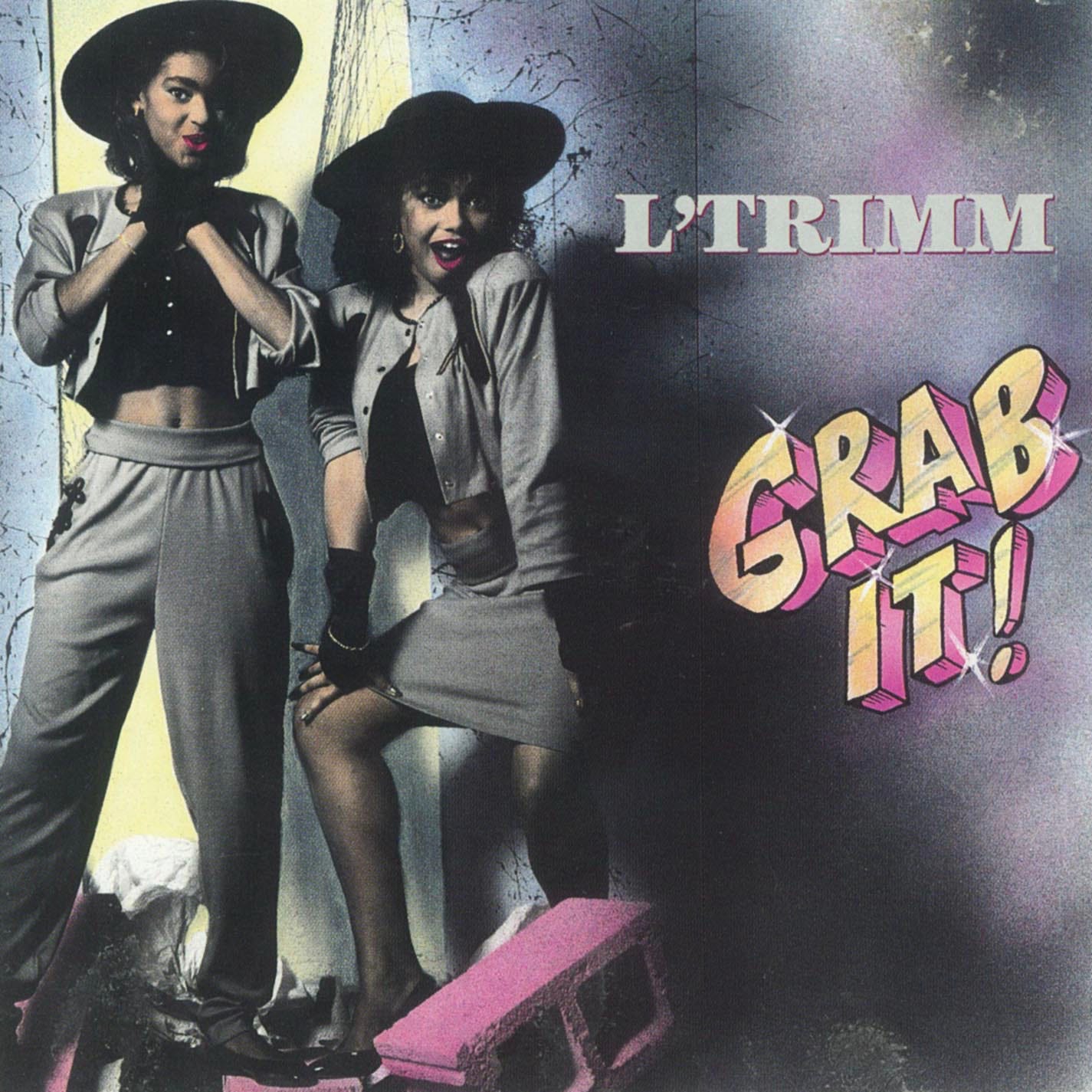

L’Trimm, Grab It!

L’Trimm were two energetic teenagers from Miami. They launched Grab It! in 1988, putting Lady Tigra and Bunny D in the spotlight as they harnessed a bouncy bass formula that captured local attention. A team of studio professionals guided the technical aspects, but the duo’s charm stood at the heart of each track. Instead of following the gritty paths carved by many East Coast or West Coast MCs, these young performers doubled down on carefree lyrics and a crisp, danceable beat. “Cars That Go Boom” was the song that shot them to wider notice, receiving spins on multiple stations that appreciated its catchy refrain and flirtatious commentary.

Building on the playful tradition glimpsed in other female rap projects, they put a bright face on competition with men, poking fun at macho stereotypes while still claiming the spotlight. Their brand of self-assured delivery stood apart from gloomier productions, allowing them to cut through the noise of the late ’80s hip-hop scene. Even if Grab It! did not dominate national charts in the same way as certain major releases, its local success signaled to fellow female MCs that there was room for laughter and party-focused content. Over time, that lesson found new life with later acts who opted for humor over confrontation, proving that the Miami duo’s gambit could inspire others searching for an upbeat spin on rap’s creative possibilities.

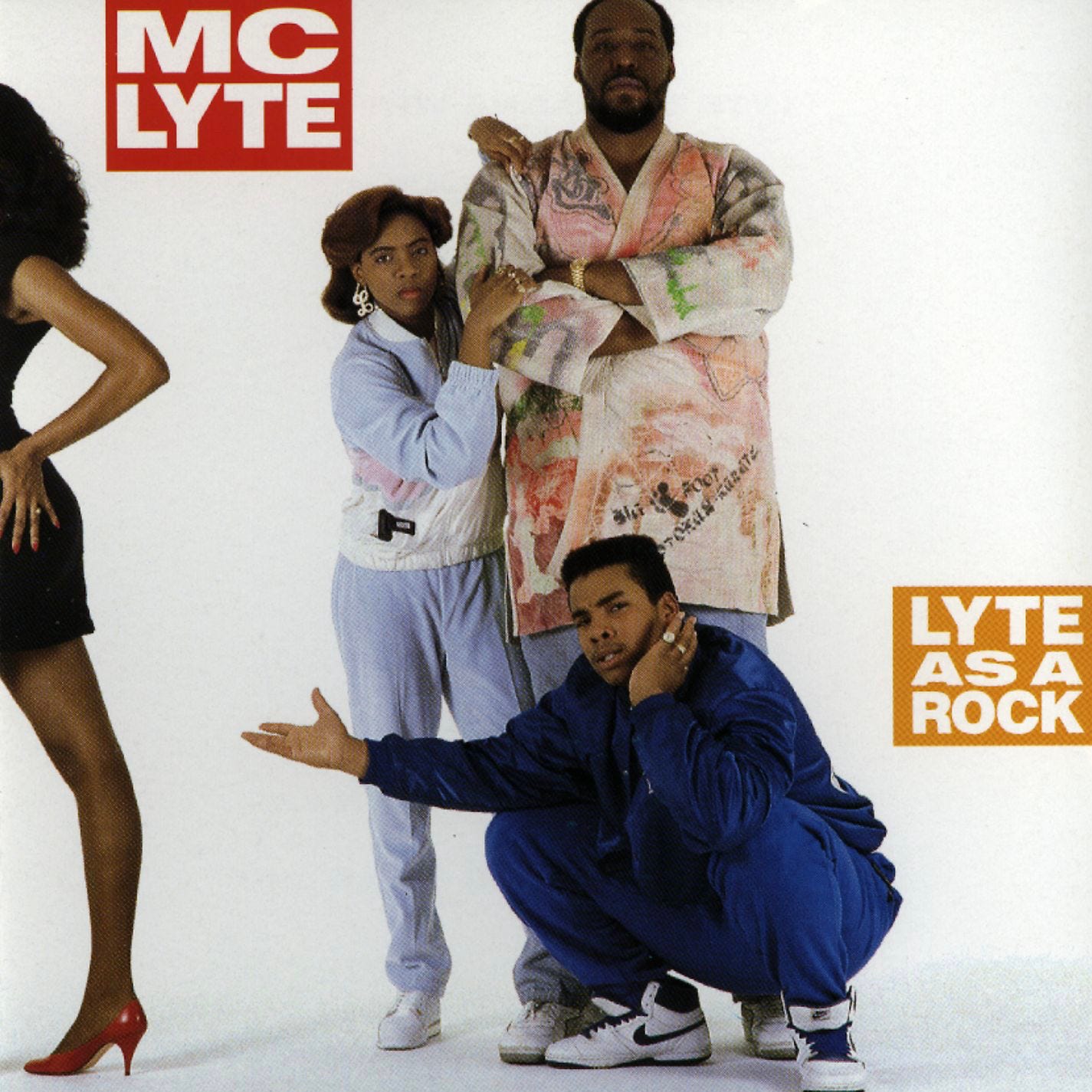

MC Lyte, Lyte As a Rock

MC Lyte is the first grand dame of rap. The album that launched her career was also the first ever released by a solo female rapper. Yet for Lana Moorer—her real name—success did not come easily at first. She owed it partly to Nat Robinson, the boss of the label First Priority. While the major label Atlantic was courting his two sons (the duo Audio Two, whom he managed), he insisted that they sign the young girl from Brooklyn. She was not yet eighteen and was so close to the Robinson brothers that she was often described (incorrectly) as their sister. Nonetheless, she left a much deeper mark on rap history than they did, thanks especially to Lyte As a Rock. However, the rapper did not overemphasize her femininity. Her appearance, like her stage name, was unisex. And from the album cover, it was not immediately obvious that the author of this first album was the petite woman dressed in white in the center.

Sometimes, though, MC Lyte did take the side of her gender. That was the case, for example, on “I Am Woman,” whose title paraphrased the famous Helen Reddy song—an anthem of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the United States. It was also true on “Big Girls Don’t Cry” and “Paper Thin,” where she urged her fellow women to be strong and break free from faithless partners. Yet overall, the rapper sought to stand out through her confidence on the mic and her verbal mastery. She wanted to compete on the men’s field and beat them at their own game. Like them, she proudly represented her neighborhood on “Kickin’ 4 Brooklyn.” On “10% Dis,” she tore into a rival, Antoinette, accusing her of plagiarizing “Top Billin’,” Audio Two’s (only) hit. She confidently tackled all the popular rap exercises of the day: fiery ego trips or socially oriented storytelling on “I Cram to Understand U,” a track about a love story ruined by crack addiction, which she wrote at sixteen (or possibly at twelve, according to some sources1). In reality, MC Lyte did not want to present herself as a great female rapper but rather as a great rap artist, pure and simple, without regard to gender. And if one overlooks a production handled by Audio Two and a few others (including Prince Paul of Stetsasonic) that bears the mark of its time a bit too strongly, she managed it brilliantly.

Also check out: Eyes On This (1989)

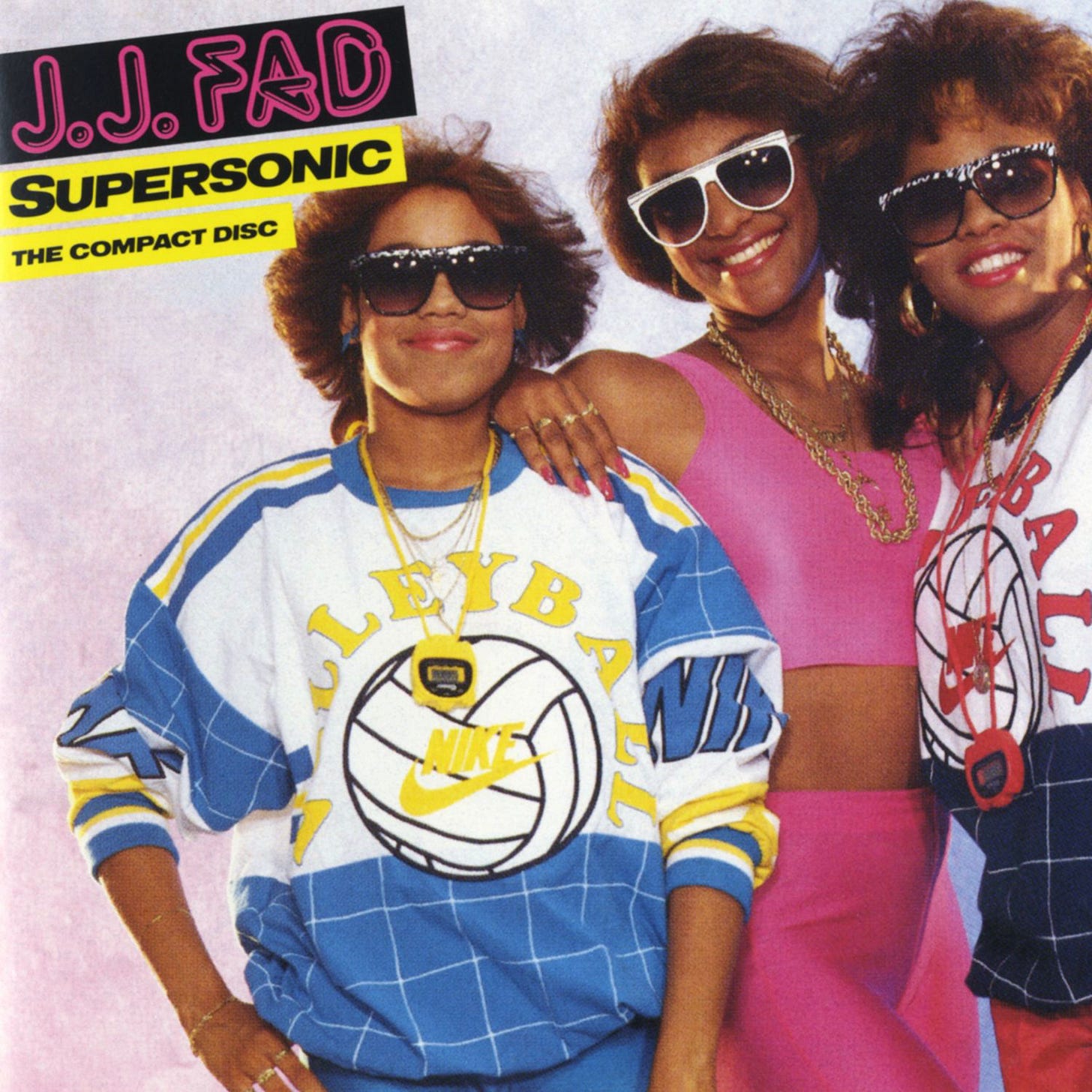

J.J. Fad, Supersonic

A new arrival in the late-‘80s rap field: Supersonic, brought forward by J.J. Fad under Ruthless Records. The group included MC J.B. (Juana Burns), Baby-D (Dania Birks), and Sassy C (Michelle Franklin), three women from California who had the backing of producer Arabian Prince, along with contributions from Dr. Dre. The record introduced a bright, energetic style at a time when female voices were still breaking into the mainstream. By blending speedy rhymes with a playful attitude, J.J. Fad achieved recognition that paralleled other West Coast acts. Eazy-E saw potential in their approach, which led to them becoming one of the earliest successes on his label. It did not heavily alter the core features of mainstream rap at that moment, but it placed female performers in a new position. The trio’s quick deliveries, set against electro-infused backdrops, emphasized skill and confidence rather than reflective themes. J.J. Fad operated much like their male peers who were experimenting with computerized beats by focusing on speed, catchy hooks, and a carefree image. In later releases, they continued to build on this template, showing that women could claim their own space in rap while maintaining a dance-friendly angle.

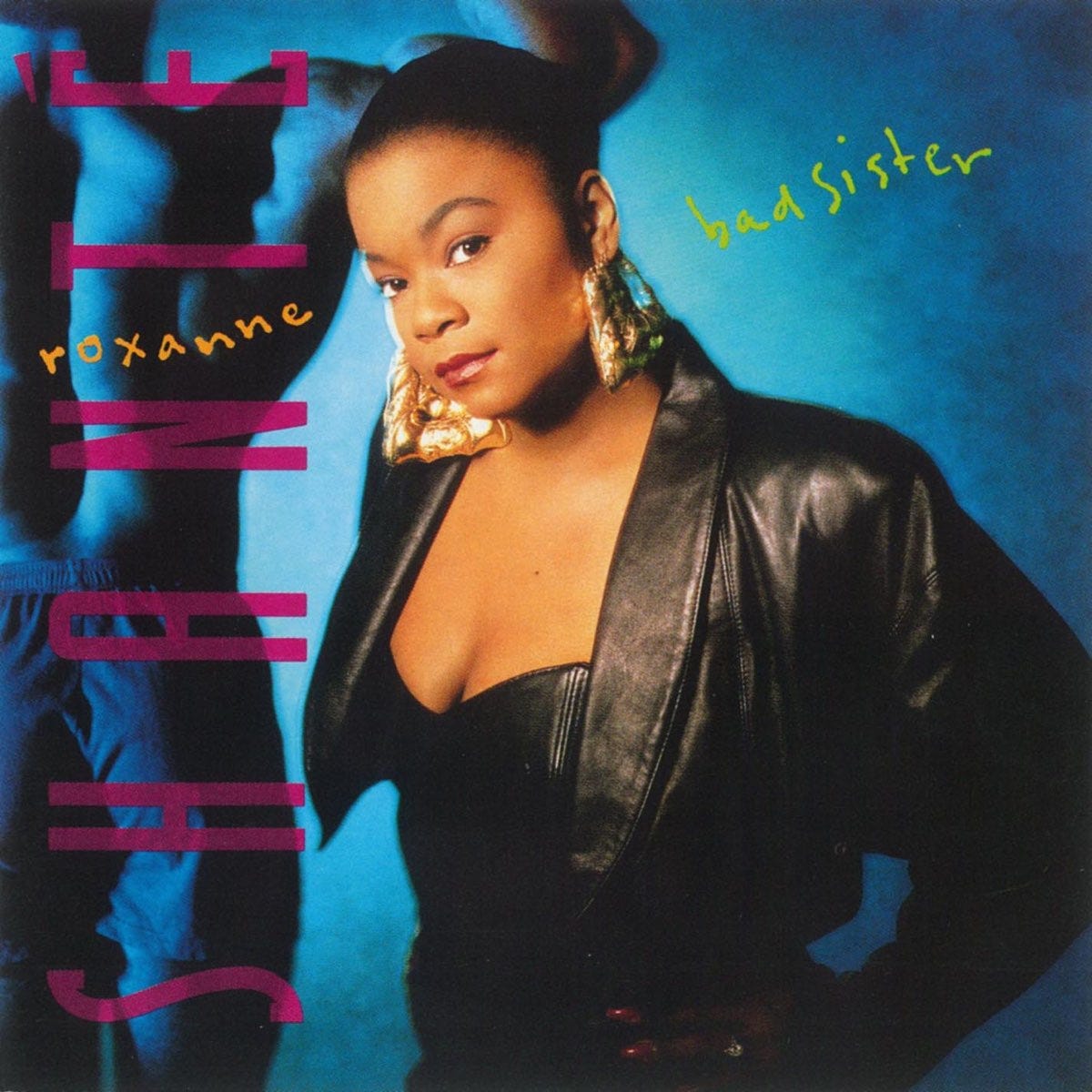

Roxanne Shanté, Bad Sister

Roxanne Shanté was just nineteen when her first album was released. And yet it came out too late—five long years after the Queens teenager had first gained fame. Many things happened in her personal life in the meantime, as recounted in the (admittedly dramatized) 2017 biopic Roxanne Roxanne. In truth, she likely was not an “album artist.” Lolita Shanté Gooden made her reputation first and foremost with her improvisation and battle rap talent. That began in her neighborhood, before she conquered the entire hip-hop scene with the verve and aggression she delivered on the historic “Roxanne’s Revenge.” Recorded with Marley Marl, a future legendary producer, this hit reused the sounds of “Roxanne, Roxanne” by U.T.F.O. only to criticize them and tear into them. In doing so—and because a multitude of other tracks were released in response to hers—Roxanne Shanté launched the first great beef in hip-hop history, known today as the “Roxanne Wars”; before another succeeded it, the “Bridge Wars,” in which Shanté, Marley Marl, and the Juice Crew also participated.

When it was time to claim her superiority over her opponent, the rapper shone. But her first album itself was rather generic. It abided by all the usual conventions of the time: ego trips, her specialty, on “My Groove Gets Better” and a remix of “Have a Nice Day” (her contribution to the Bridge Wars); beatboxing on “Bad Sister” (only natural for someone close to Biz Markie, a master of the genre); house music excursions on “Live On Stage” and “Go On Girl.” Naturally, Shanté also sided with her fellow women on feminist sections. She exhorted them to break free from men’s clutches on “Independent Woman” and in the storytelling track “Fatal Attraction.” This variety, along with Marley Marl’s production, made Bad Sister a solid, enjoyable album. But it was not unique enough to rekindle the career of a rapper who, faced with her responsibilities as a young mother and other personal constraints, released just one more album before the above-mentioned film, much later, reminded people of the key place she occupied in rap history.

Also check out: The Bitch Is Back (1992)

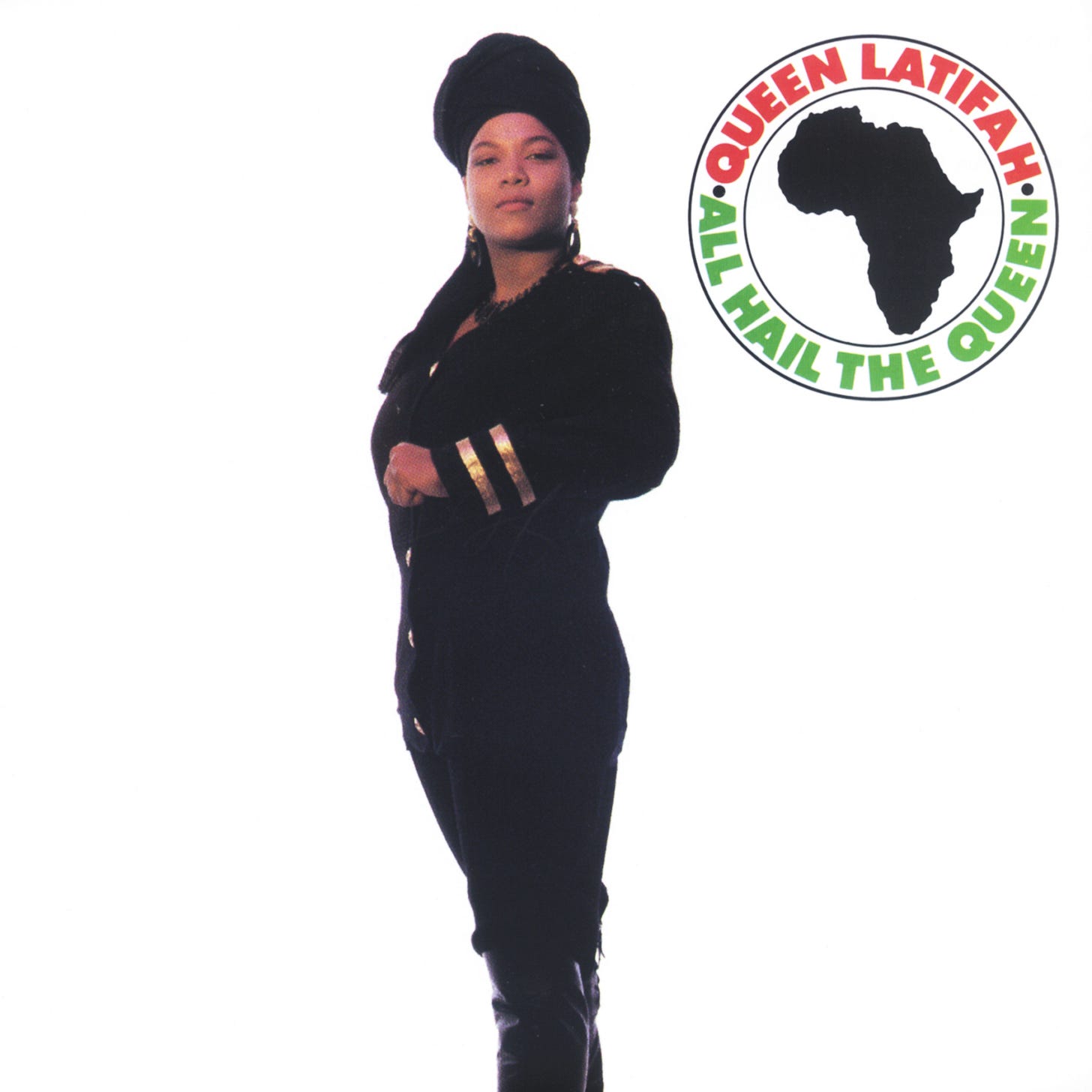

Queen Latifah, All Hail the Queen

As curious as it may seem, one of the first great voices of female rap—one of those who wanted to imbue her lyrics with meaning—started out in a marginal branch of hip-hop culture: beatboxing. Dana Owens, a native of New Jersey who would later choose the name Latifah (“sensitive, delicate” in Arabic), was in charge of that exercise in an all-female group, Ladies Fresh. Gradually, she switched to rap, joined the Flavor Unit collective, and later became part of the large Native Tongues family. Through Fab 5 Freddy, then host of Yo! MTV Raps, she also signed with Tommy Boy, which released her first album. Produced by DJ Mark the 45 King of the Flavor Unit, All Hail the Queen was in step with its time. It featured good-natured ego trips and funky samples on tracks like “Queen of Royal Badness,” “Wrath of My Madness,” and “Dance for Me,” along with celebrations of the DJ/MC bond on “A King and Queen Creation.” It almost seemed ordinary. But we also heard the Native Tongues’ distinctive touches: whimsy, with the track “Mama Gave Birth to the Soul Children,” produced by Prince Paul and performed with De La Soul, plus a broad musical openness.

Other genres besides hip-hop were widely present: reggae on “The Pros,” “Princess of the Posse,” and in the choruses of “Wrath of My Madness” and “Inside Out”; house music (or more precisely hip house) on “Come Into My House”; and Latin music on “Latifah’s Law.” All of this hinted at the multidimensionality of Queen Latifah, who would later become a jazz and soul singer, as well as a recognized actress. We also discover on this first album another of her characteristics: her activism, her position as a conscious rapper. On “Evil That Men Do,” for example, she and KRS-One condemned the world’s injustices. And on “Latifah’s Law,” she stood up for women, showing that she refused to be dominated or dictated to. She also did so on the album’s best track, “Ladies First,” a statement in favor of women that she performed with the English rapper Monie Love, the other female member of the Native Tongues. That track, along with another great anthem on the same topic, the historic “U.N.I.T.Y.,” helped establish Queen Latifah’s status in rap history as a major feminist figure.

Also check out: Black Reign (1993)

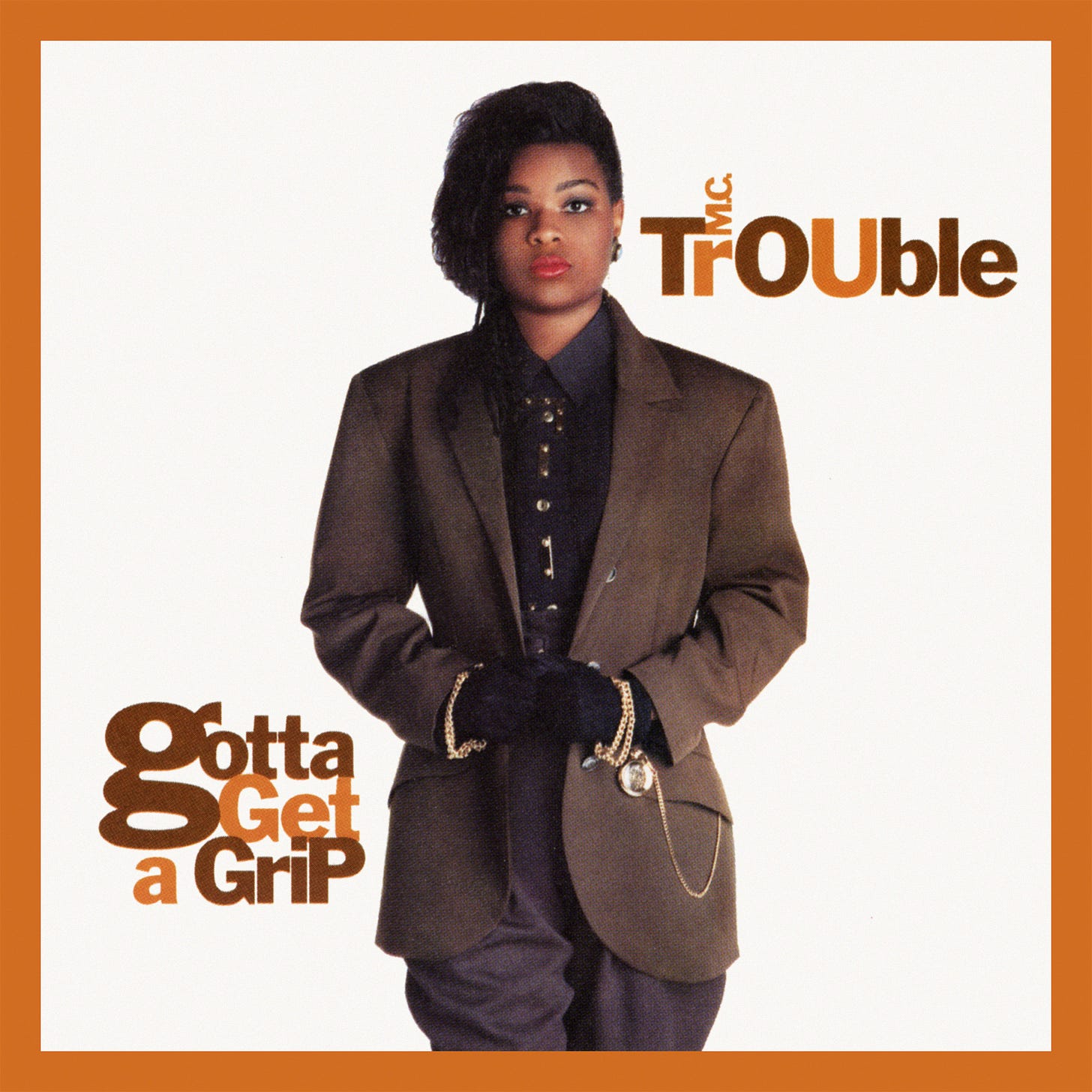

M.C. Trouble, Gotta Get a Grip

Few labels embody the legend of African-American music as much as Motown. Yet the venerable house built by Berry Gordy was slow to take an interest in the hip-hop phenomenon. Like much of the old soul and funk guard, Motown once viewed this new music with caution, even hostility, leaving the independent labels Sugar Hill, Profile, Tommy Boy, and Def Jam to proudly champion it. In the late 1980s, however, the company began looking more closely at the new cash cow, signing rappers like Jesse West (aka 3rd Eye) and M.C. Brains, as well as a young Los Angeles native: LaTasha Rogers, aka M.C. Trouble. In many respects, her music did not clash with Motown’s. Her single (and biggest success), “(I Wanna) Make You Mine,” was a simple declaration of love to an ideal man and featured The Good Girls, a trio often likened to a modern version of The Supremes.

Her album, Gotta Get a Grip, had a retro feel, with its rather old-fashioned funky groove, its focus on love, and its sung sections like “Thing gor You.” But overall, M.C. Trouble was indeed a rapper who showed presence, assurance, and fire on the mic. She performed ego trips and battle-style rap on “Here Comes Trouble” and “Points Proven.” She came across as political, angry, and pro-Black on “Black Line,” as well as on the title track “Gotta Get a Grip,” over spare production full of furious scratching. On the romance “(I Wanna) Make You Mine,” for a few lines, the rapper insisted she was no angel. And when she described her types of men on “Fly Guy,” she did so humorously and brashly, praising their large rears. M.C. Trouble had potential; she might have had a long career. But fate cruelly decided otherwise. Since childhood, she had suffered from epilepsy, and in 1991, at the age of twenty, while working on her second album, she died of a heart attack. Only a few of her peers remember her. Q-Tip mentioned her by name at the end of “Vibes and Stuff,” a track on the classic A Tribe Called Quest album The Low End Theory. And another rapper, Nefertiti, paid her a more explicit tribute on the track “Trouble In Paradise” at the end of the album L.I.F.E.: Living In Fear of Extinction.

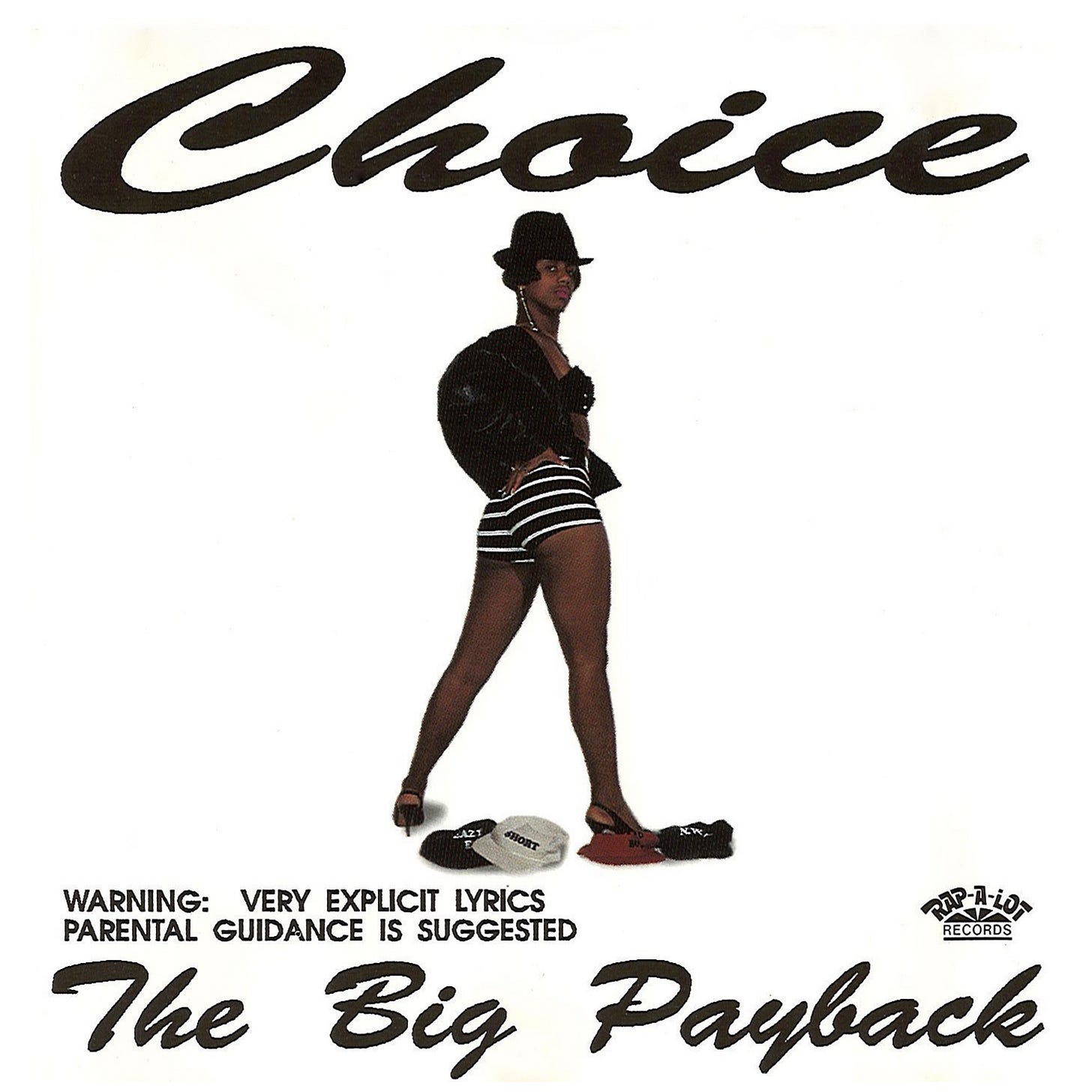

Choice, The Big Payback

In Houston, Texas, with the Geto Boys and a few others, the worst excesses of gangsta rap were first practiced. And it was there, too, that the earliest examples of extreme female hip-hop surfaced, with Kim Davis, aka Choice. She initially made herself known alongside one of the members of that aforementioned group. From her track “I Need Some Pussy” on Willie D.’s first solo album, she set the tone, adhering to the usual clichés of the genre and offering to please him with a vagina she described as as big as Bolivia. A year later, when the time came for her to release her own album, she continued down the same path. With a rap style (funky sounds, a strong taste for storytelling) still largely influenced by the New York model, Choice unleashed a long string of insults and obscenities. She proudly claimed to be a “Bad Ass Bitch” and openly said she preferred, without ambiguity, particularly hard penises. She shared her fantasies with appropriate moans (“Pipe Dreams”), launched into an ode to oral sex (“Nothing But Sex”), instructed men on how to provide cunnilingus correctly (“Cat Got Your Tongue”), and railed against those who climax too quickly (“Minute Man”).

All the themes of pornographic female rap, the kind that would flourish at the end of the decade, were already present on The Big Payback. Choice was its great pioneer, ahead of her time. And she paid for it: sadly, success did not arrive. Indeed, with a sturdy frame that caused some to compare her to a drag queen, she lacked the visual assets of Lil’ Kim or Foxy Brown. Nor did she make the best career choices when she targeted all the then-stars of gangsta rap. On the album’s cover, she is shown stomping on caps bearing their names. And on the track “Payback,” she hurled insults at none other than Too $hort, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, and the entire N.W.A., along with the Geto Boys of her collaborator Willie D. The latter responded to the rapper’s attacks with a violent “Little Hooker” on his album I’m Goin’ Out Lika Soldier. Despite making some waves at first—and despite a second album titled Stick-N-Moove in 1992—Choice then disappeared from the radar, leaving other female rappers to triumph with a formula she had tested for them first.

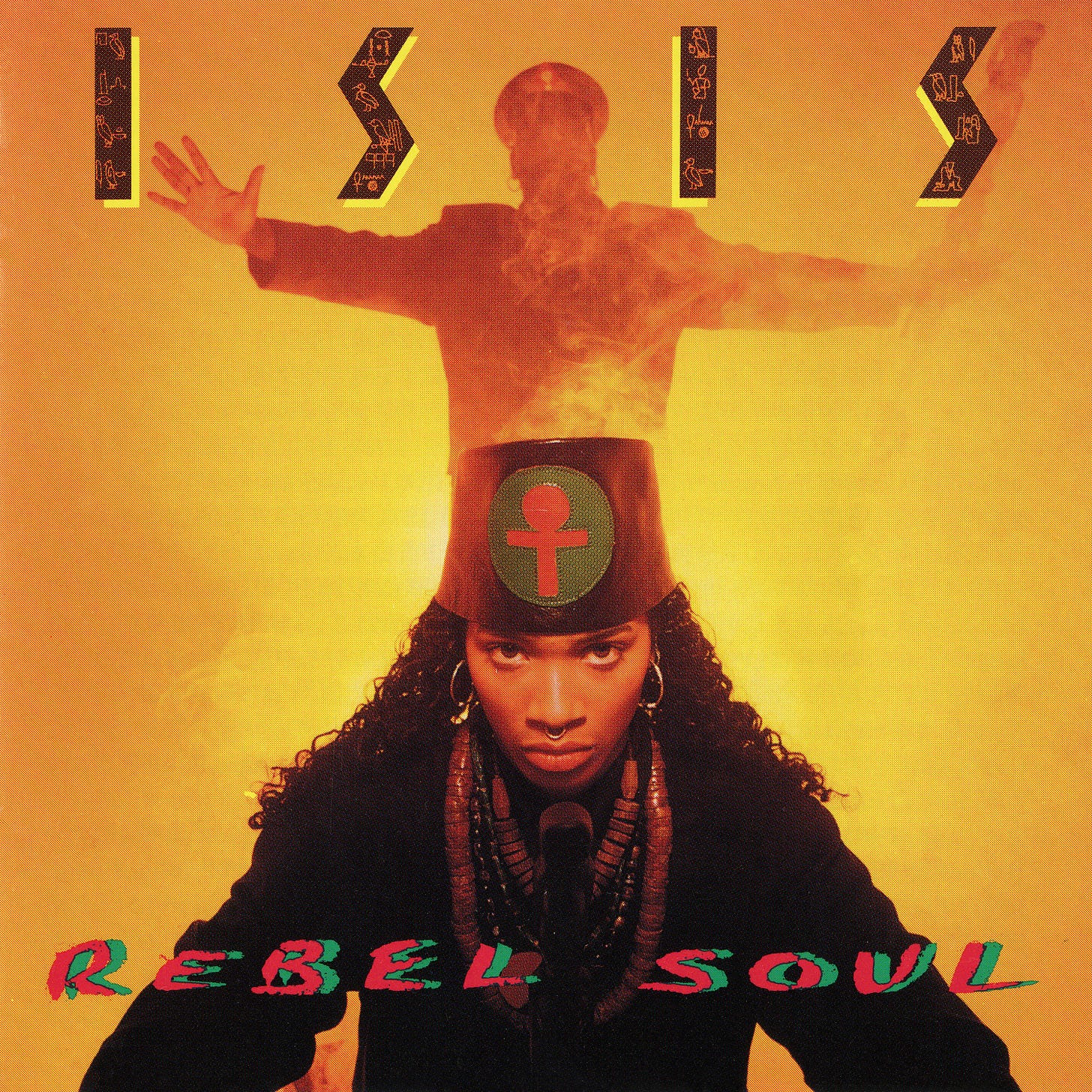

Isis, Rebel Soul

From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, no group better embodied the Afrocentric phase rap was going through than the X-Clan and its Blackwatch Movement collective. Led in part by Professor X, the son of African-American activist Sonny Carson, they promoted a Black nationalist program tinged with millenarian and conspiracy views of varying seriousness. One distinctive feature of this group was that it welcomed two women: Queen Mother Rage and Lin Que Ayoun. The latter, who, in line with the Egyptian themes then in vogue, rapped under the name of the goddess Isis, named her album Rebel Soul. That record bore all the signs of this school of rap: Africa was a major reference, heard in the percussion and chanting that adorned the album, and politics was at the heart of the discourse as the young woman opted for radical, revolutionary language, sometimes taking a feminist stance, as on “Great Pimpstress.” Yet a man oversaw her destiny.

As predicted by the cover, where he appears in the background in majestic form, Professor X is omnipresent. He made appearances on the album with lines that resembled slogans or political sermons more than rap. He became downright invasive. That was one limitation of the project, as was its dated side. Indeed, Rebel Soul stands as a relic of a bygone era, not only for its Afrocentrism but also for its era-marked sounds: funk and frequent excursions into house music (“Face The Bass,” “Hail the Words of Isis,” “The House of Isis”). Nevertheless, Isis could rap. She demonstrated that throughout, with force, confidence, and conviction. For that reason, this album has little to envy from the X Clan record that came out the same year, their classic To the East, Blackwards. It had no real follow-up, however. Afterward, Lin Que wrote lyrics for her friend MC Lyte, did some production work, and briefly joined Deadly Venoms, a group of female rappers affiliated with the Wu-Tang Clan. But this strong-willed individual struggled to reach an agreement with her labels, and despite a few sporadic releases, including a second self-produced album in 2007, she chiefly devoted herself to her family.

Also recommended: Queen Mother Rage, Vanglorious Law (1990)

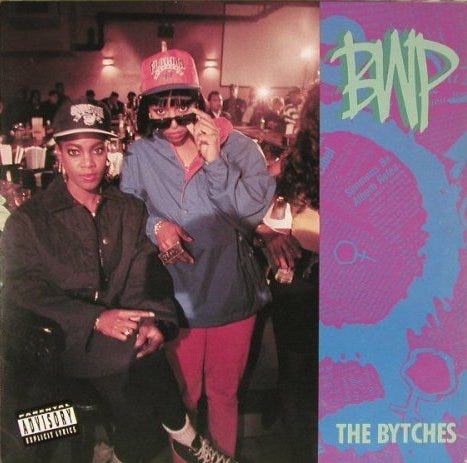

BWP, The Bytches

The only album by Bytches With Problems—at least the only one commercially released (another, Life’s a Bytch, slated for 1993, never saw the light of day)—starts off harshly. “Hey, bitch, how’s it going?” a man asks. To which his interlocutor answers, “Not bad, motherfucker. And your whore of a mother?” Instantly, the stage is set. With those opening words, the duo shows they play in the same league as the least respectable of their male counterparts. Lyndah McCaskill and Tanisha Michele Morgan may be New Yorkers, but they’re following in the footsteps of Californian gangsta rap (or even the Floridian dirty rap of 2 Live Crew). With filthy language and an aggressive stance, they talk about guns and murder (“Hit Man”), police harassment (“Wanted”), money (“We Want Money”), or else Lyndah insolently chides her white boss for being inconvenienced by her period (“Cotex”). Above all, sex remains a constant in their lyrics. Pornographic language doesn’t bother them, but the two members of BWP use it from a female perspective, as in “Teach Em,” which discusses teaching their partners how to perform cunnilingus properly.

They attack men violently, deploying the same onslaught of insults and disdain that sexist male rappers routinely direct at women. They twist those vile misogynistic slurs. Immediately evident in the introduction’s dialogue, this hostility toward men is another distinctive trait of BWP. “Comin’ Back Strapped” and “Fuck a Man” are two such tracks where they excel at tearing male jerks apart. On “Shit Popper,” Lyndah encourages an abused woman to kill her lover in his sleep. On “No Means No,” they vehemently say “no” to overly pushy guys. On “Two Minute Brother,” they show their contempt for men who finish too quickly in bed. And when, in the end, they do give in to them—like Lyndah on “Is the Pussy Still Good?”—it’s only to enjoy it and then toss them aside. Even if their formula is not fully fleshed out yet, even if Lyndah and Tanisha Michele remain anchored in old-school rap with their funky sounds, their implacable Public Enemy-style beats, and their plain style of dress, they hint—through their boldness—at the carefree female rappers who would become the norm a few years later.

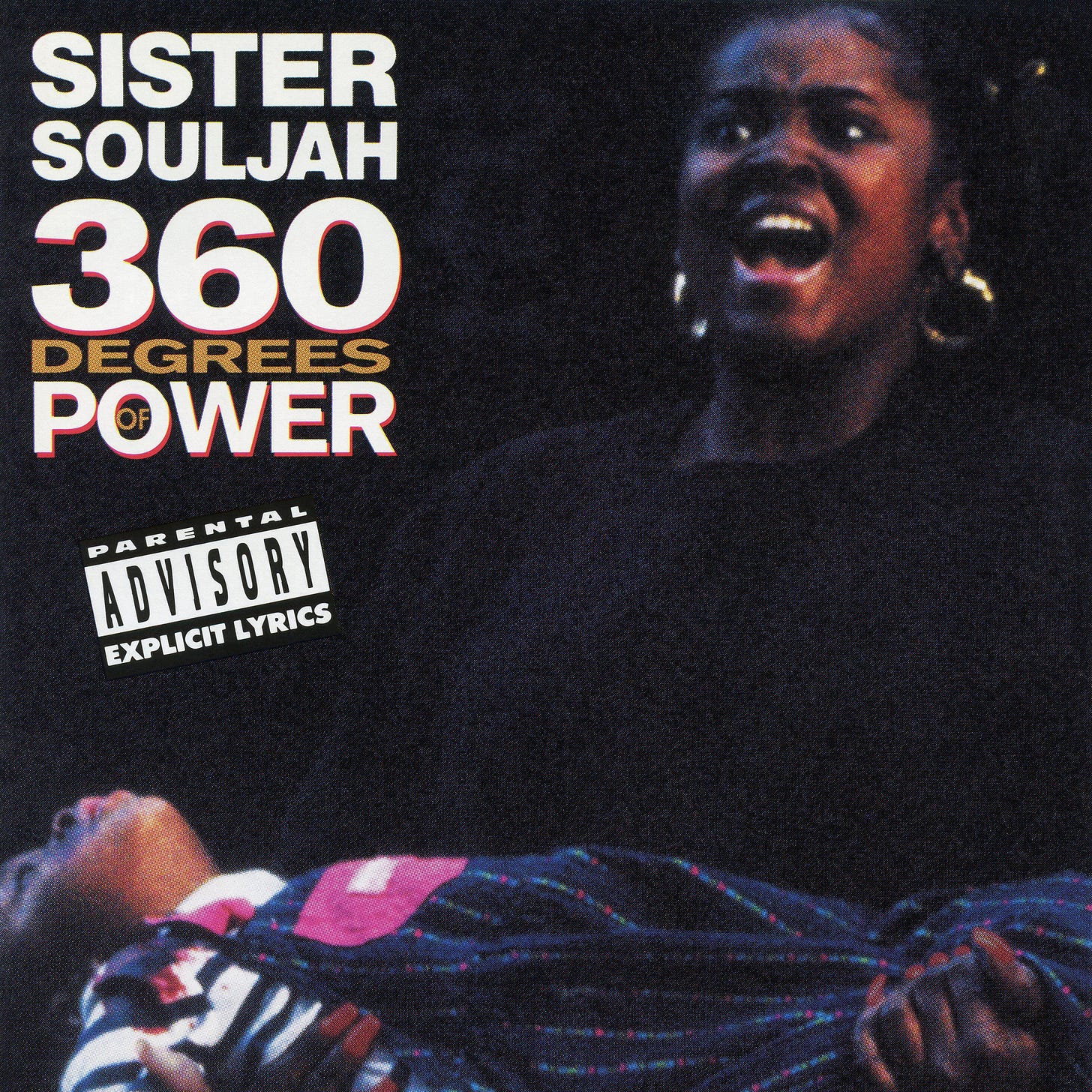

Sister Souljah, 360 Degrees of Power

A “Sister Souljah moment,” in American political jargon, refers to a tactic where a candidate denounces the most extreme members of his or her own camp to win favor with moderates and undecided voters. The phrase dates back to the 1992 presidential campaign when Bill Clinton attacked someone close to Jesse Jackson: the rapper Sista Souljah. She had declared in the context of the Los Angeles riots, “If Black people kill Black people every day, why not take a week to kill white people?” In a show of moral posturing, the future President denounced the supposed extremism of his Democratic rival’s circle. Today, America remembers Sister Souljah for that moment more than for her music, which makes sense: above all, she was and always has been an activist. A graduate in American history and African studies, Lisa Williamson spent the 1980s fighting violence and racism in her country and became involved in volunteer work in several African nations, opposing Apartheid. From 1999 onward, she became a novelist, publishing socially engaged books about prison life. Meanwhile, her spell in rap happened under the umbrella of the most political group of all, Public Enemy, of which she was briefly an official member.

Her only album illustrates that stance: it is less a rap record than one of lengthy, furious sermons and fiery harangues, following the tradition of the great orators of the Civil Rights Movement. Over the abrasive, angry sounds typical of the production collective The Bomb Squad, with lyrics so blunt MTV censored her, and with only the two loudest voices of political rap—Chuck D and Ice Cube—as guests, Sister Souljah unleashed her hatred of a racist, white-supremacist America on “The Final Solution: Slavery’s Back In Effect,” “Killing Me Softly: Deadly Code of Silence,” “Brainteasers and Doubtbusters,” and “My God Is a Powerful God.” But she was no kinder to her fellow Black people, urging them to stop keeping their heads down and to show pride. She likewise called on Black women to awaken. She celebrated their strength on “360 Degrees of Power.” She urged them to raise the soldiers of the future on “Umbilical Cord to the Future.” And on “The Tom Selloutkin Show,” she advised them not to give themselves to men without receiving something in return. From start to finish, the rapper portrayed herself as a secular preacher. That was her strength, and it was also the limit of this powerful but draining album.

Yo-Yo, Black Pearl

Anyone who condemns gangsta rap too quickly by citing its heightened misogyny should pay attention to “It’s a Man’s World.” Released in 1990, on Ice Cube’s first solo album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, it once again allowed the former N.W.A. rapper to spew his contempt for women. But on this track, he also allowed his protégé, the rapper Yo-Yo, to strongly contradict him, to oppose a female voice to his forcefully. Indeed, although Yolanda Whitaker was right in the thick of the Californian gangsta scene (for a while, she was even dating 2Pac), she never stopped defending women—both in real life (eventually founding the Intelligent Black Women’s Coalition) and on records. This was the case on Black Pearl, her second album, for which she had more artistic freedom than her previous work. Except for the somewhat off-topic romantic finale of “Will You Be Mine,” most of the tracks on this release allowed her to represent her African-American sisters. On “Black Pearl” and “Can’t Take No More,” she urged them to be strong and resilient. On “Home Girl Don’t Play Dat,” she offered them survival tips for the urban jungle, but with “Cleopatra,” she imagined herself as a superhero restoring their honor.

And when she wasn’t defending women, Yo-Yo was attacking men. On “You Should Have Listened,” she denounced their cheating, as on “Woman to Woman,” where she firmly advised a betrayed woman to blame the husband rather than the mistress. On “Hoes,” she threw that favorite misogynistic slur back at men who accumulated sexual conquests. She took up gangsta vocabulary but flipped the perspective. Indeed, her raps did not run counter to Ice Cube’s; they mirrored them perfectly. Her fast-paced music, founded on funky effectiveness, her violent and committed lyrics hurled with urgency and power, her pride, her anger, and her urgent desire to be heard—all were exactly the same as her mentor’s. Only the viewpoint changed. No longer the male frustrations of a street kid but the thirst for recognition of a young African-American woman in a Californian scene more diverse than its detractors imagine.

Also check out: Make Way for the Motherlode (1991), You Better Ask Somebody (1993)

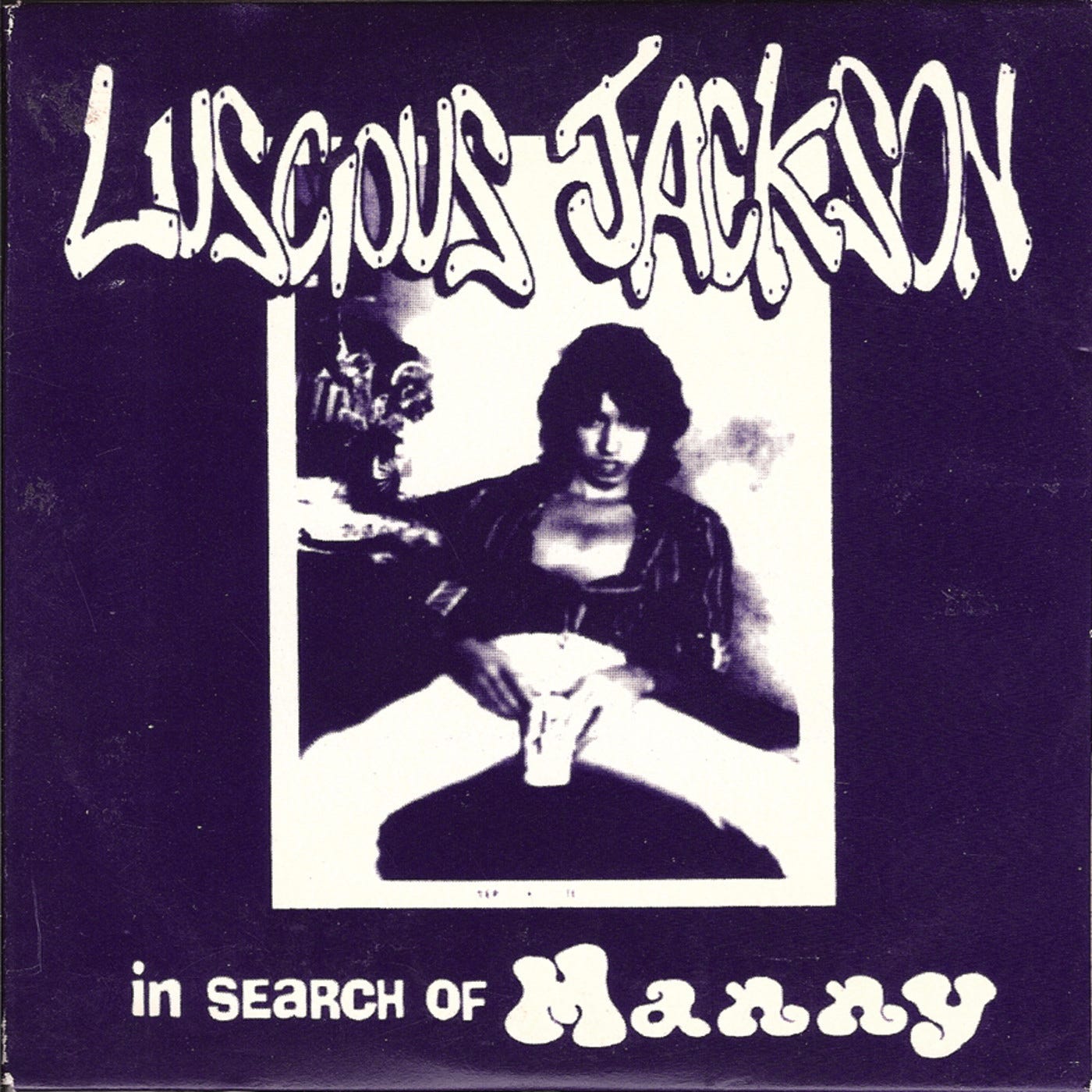

Luscious Jackson, In Search of Manny

Jill Cunniff, Gabrielle Glaser, Kate Schellenbach, and later Vivian Trimble, the four members of Luscious Jackson, are often labeled the female Beastie Boys, not without reason. This East Village band was the first to join Grand Royal, the label founded by the New York trio. And a decade earlier, in the early 1980s, when the Beasties were still a hardcore punk group, Kate was the drummer on their first EP, Polly Wog Stew. In fact, she was the one who introduced them to what was originally just a duo formed by bassist Jill and guitarist Gabby. Thus, the link between the two groups is obvious, and it resonates in the music of the four women—a style perched at equal distances between hip-hop and alternative rock, similar to the approach the three men took on their third album, the eclectic Check Your Head. These white women, late heirs to the era when New York’s new wave scene was discovering hip-hop, borrowed heavily from that genre on their first EP.

In Search of Manny—which collected three demos and four original tracks—saw them rapping most of the time. Their drum machines, taste for sampling, and sonic collages came from hip-hop. Funk influenced them as well, as when they sampled Funkadelic on “Life of Leisure” or offered an instrumental, “Bam-Bam,” featuring blaxploitation-sounding elements. Jill and Gabby also sang, even delivering lovely vocal harmonies. The guitar, whether acoustic or electric, was prominent. And the lyrics, subtle and somewhat feminist, were delivered in small touches, without the direct verbosity typical of the rap of that time. As the EP progressed, on tracks like “Keep On Rockin’ It” and “Satellite,” In Search of Manny took an increasingly clear rock direction. Luscious Jackson would continue that general shift on later albums. In 1996 and 1997, at the peak of their fame with the single “Naked Eye” and the undervalued side project Kostars (led by Vivian and Jill), the band purely played indie pop. Nonetheless, this first EP remains testimony—along with works by Beck and the Beastie Boys—to what hip-hop and alternative rock, the two most popular genres in America of the early 1990s, could accomplish at their best when they joined forces.

Also check out: Natural Ingredients (1994), Fever In, Fever Out (1996)

Also recommended: Kostars, Klassics With a “K” (1996)

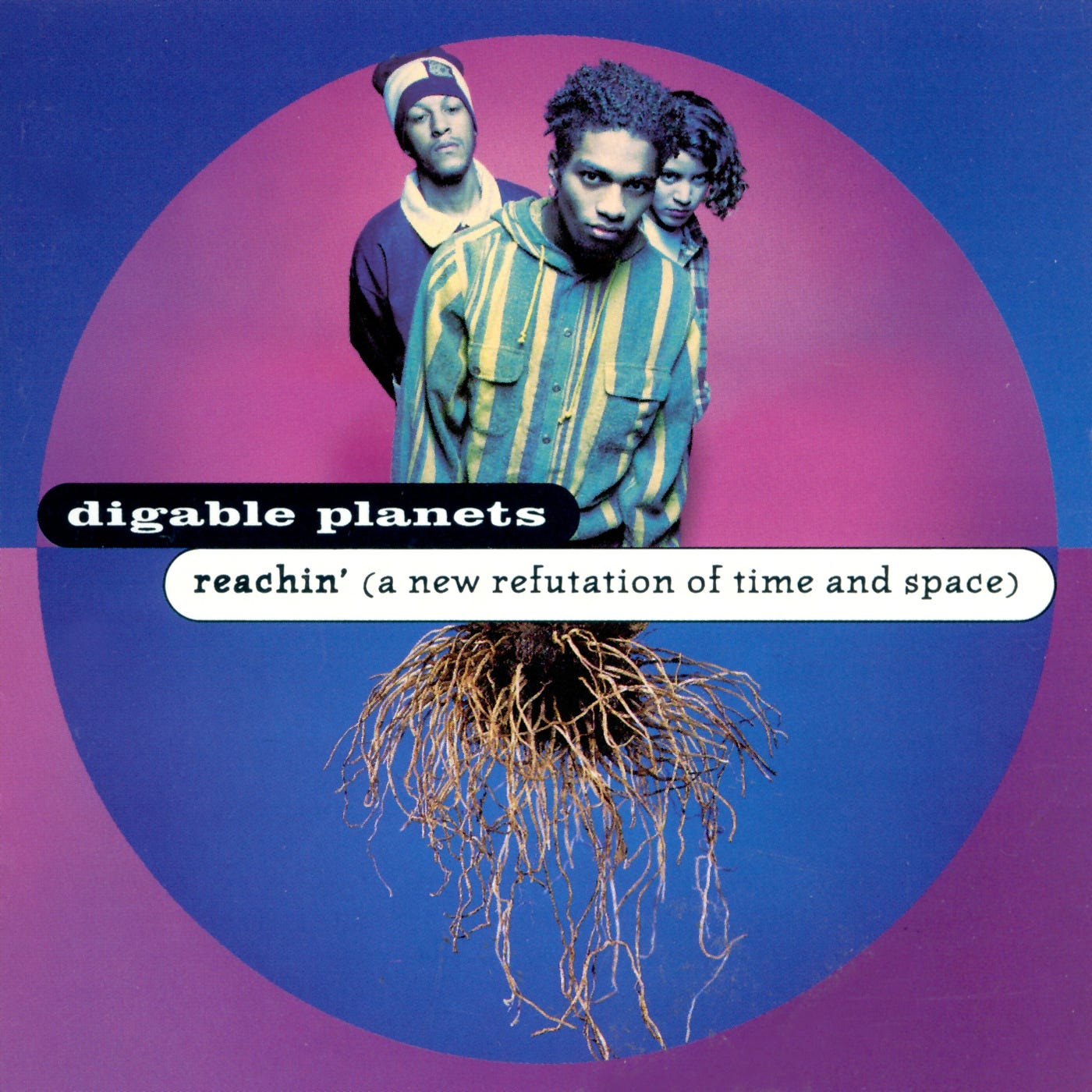

Digable Planets, Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space)

One of the major trends in rap during the first half of the 1990s was its renewed ties with jazz. The Native Tongues collective, and more specifically A Tribe Called Quest with its landmark album The Low End Theory, as well as the duo Gang Starr—together or via the Jazzmatazz project led by its rapper Guru—were the most famous standard-bearers for this important phase in rap history. To those names, one should add the trio Digable Planets, who popularized this subgenre to a wider audience through the success of the hit “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)” and then the album Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space). Seldom have these two musical styles fused as well as on that album, which sought to recreate the cool mood of a jazz club. The sounds and samples (Herbie Hancock, Sonnie Rollins, Art Blakey, The Crusaders, etc.) largely came from that genre, and the lyrics touched on it too, as in “Last Of The Spiddyocks,” which recalled jazzmen and their drug addictions. Moreover, the trio’s members cultivated a learned image (the album name was drawn from a Borges novel, and they cited Nietzsche, Marx, Orwell, Sartre, or Camus) in line with late jazz’s intellectual reputation.

Throughout, Digable Planets bridged the gap between jazz’s past and hip-hop’s present, aiming to present them as a continuum. One major advantage they had was having a woman among their three rappers, who chose insect names as stage aliases. Mary Ann Vieira, aka Ladybug Mecca, then the girlfriend of another band member, Craig “Doodlebug” Irving, gave the record a voice both gentle and firm, intensifying the suave aura Digable Planets sought for their music. Her languid inflections sometimes evoked the bossa nova of her birth country, Brazil, a music she would explore in more detail about a decade later on her solo album Trip the Light Fantastic. The feminine, even feminist, dimension of this first album was also emphasized by “La Femme Fetal,” a bold pro-choice track labeling its opponents as fascists. It was not, however, the rapper who spoke here, but Ishmael “Butterfly” Butler, the group’s unofficial leader, in the same calm, supple tone as on the other tracks, which only reinforced the message—practically the only one on an album that otherwise focused on the art of being cool and feeling good.

Also check out: Blowout Comb (1994)

Also recommended: Ladybug Mecca, Trip the Light Fantastic (2005)

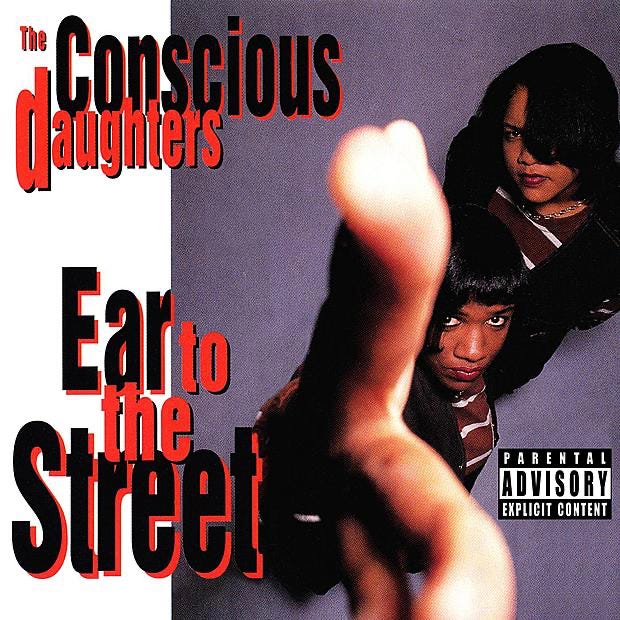

The Conscious Daughters, Ear to the Street

The Conscious Daughters both benefited from and were harmed by their association with the rapper Paris. At first, it was thanks to him that these two childhood friends from Oakland rose to the forefront. After hearing their demos, the rapper opened the door of his label, Scarface, to these peers from the San Francisco Bay, producing their entire first album. But when Paris severed ties with Priority Records, which handled his distribution, they were forced to grapple with the record industry and ended up releasing only a handful of rare, little-known albums, despite Nas attempting to bring them up to date on “Where Are They Now (West Coast Remix),” a tribute to some forgotten West Coast heroes.

Because of their connection to Paris and their name (“conscious” could be translated as “socially aware” or “politically engaged”), one might assume these women delivered a female version of their mentor’s militantly political, explosive rap. For the most part, however, Carla Green (aka CMG) and Karryl Smith (aka Special One) offered a variation on Los Angeles gangsta rap. Their biggest hit, “Something to Ride To (Fonky Expedition),” was a carefree piece built around a smooth beat and cruising stories, modeled on “Nuthin’ But a ’G’ Thang” by Dr. Dre. Another single, “Roll Deep,” followed the same approach, “Showdown” again looked to g-funk, while other tracks—like the energetic, biting “Princess Of Poetry”—fell more into the streetwise, funky, and boastful rap of Ice Cube. Nevertheless, The Conscious Daughters did show a form of social commitment, one that took a particular route: the female viewpoint. In “Wife of a Gangsta,” the two rappers recounted the difficulties faced by a criminal’s wife. On the ego trip “Crazybitchmadness,” Special One brazenly reclaimed her sexuality. “Shitty Situation” told the story of a woman struggling as a single mother after a short-lived relationship. And in “What’s a Girl to Do,” the message was even more explicit: “I don’t clean houses, I’ll clean out your bank account.” They never let go of that female banner, even while stuck in the underground, until Special One’s death in 2011.

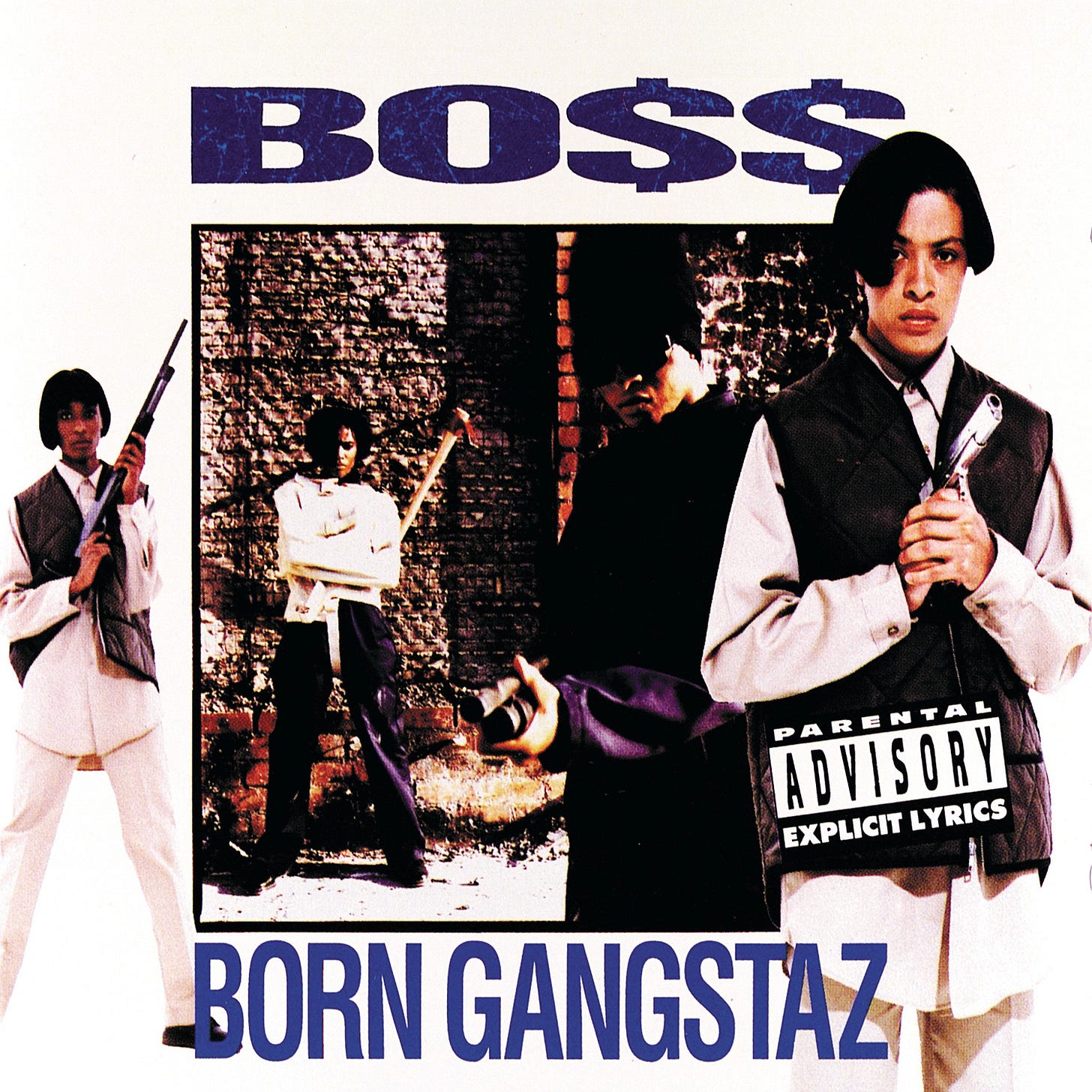

Boss, Born Gangstaz

In the early 1990s, while the Californian gangsta rap scene was dominating the United States and overshadowing the New York artists who had paved its way, Def Jam had to act. Its co-founder and president came up with the following idea: create a female counterpart to that subgenre and invest in a gangsta rapper. He focused on Boss, a duo discovered by DJ Quik that had recently appeared on an album by his collaborator AMG. He signed them, allowing them to release an album produced by some of the era’s biggest names (Def Jef, Erik Sermon, MC Serch, Jam Master Jay), which achieved a certain commercial success. Most of the above producers were from New York, and the two girls were not truly Californian (originally from Detroit—still a rap desert at the time—they had relocated to Los Angeles a few years earlier). Nevertheless, that album sounded more gangsta than gangsta itself.

Boss was also the pseudonym of Lichelle Laws, the rapper and main member of the duo (the other, less memorable, being DJ Irene Moore, aka Dee). She came from the middle class. In the album’s intro, her mother mentioned the Catholic education she received and the dance lessons she attended. Boss was also reputed to be shy and reserved. But on the mic, she transformed, speaking with aplomb and total insolence. In line with the subgenre’s codes, she cursed freely, advocated murder and violence, and praised her love of joints. She and her producers stuck so closely to California rap’s formula that the record eventually became generic and formulaic. However, the two singles, “Deeper” and “Recipe of a Hoe,” were extremely effective. They also illustrated a new kind of feminism, with Boss reclaiming for herself the derogatory terms “hoe” and “bitch,” reversing gangsta rap’s misogynistic viewpoint by showing men the same coldness and contempt they displayed toward women. In that regard, although she adopted the gangsta look that still prevailed among female rappers, Boss proved her co-founder right: she heralded the future of women’s rap. But that future came without her. A few years later, dropped by Def Jam, Lichelle Laws focused on her family life before she passed on March 11, 2024.

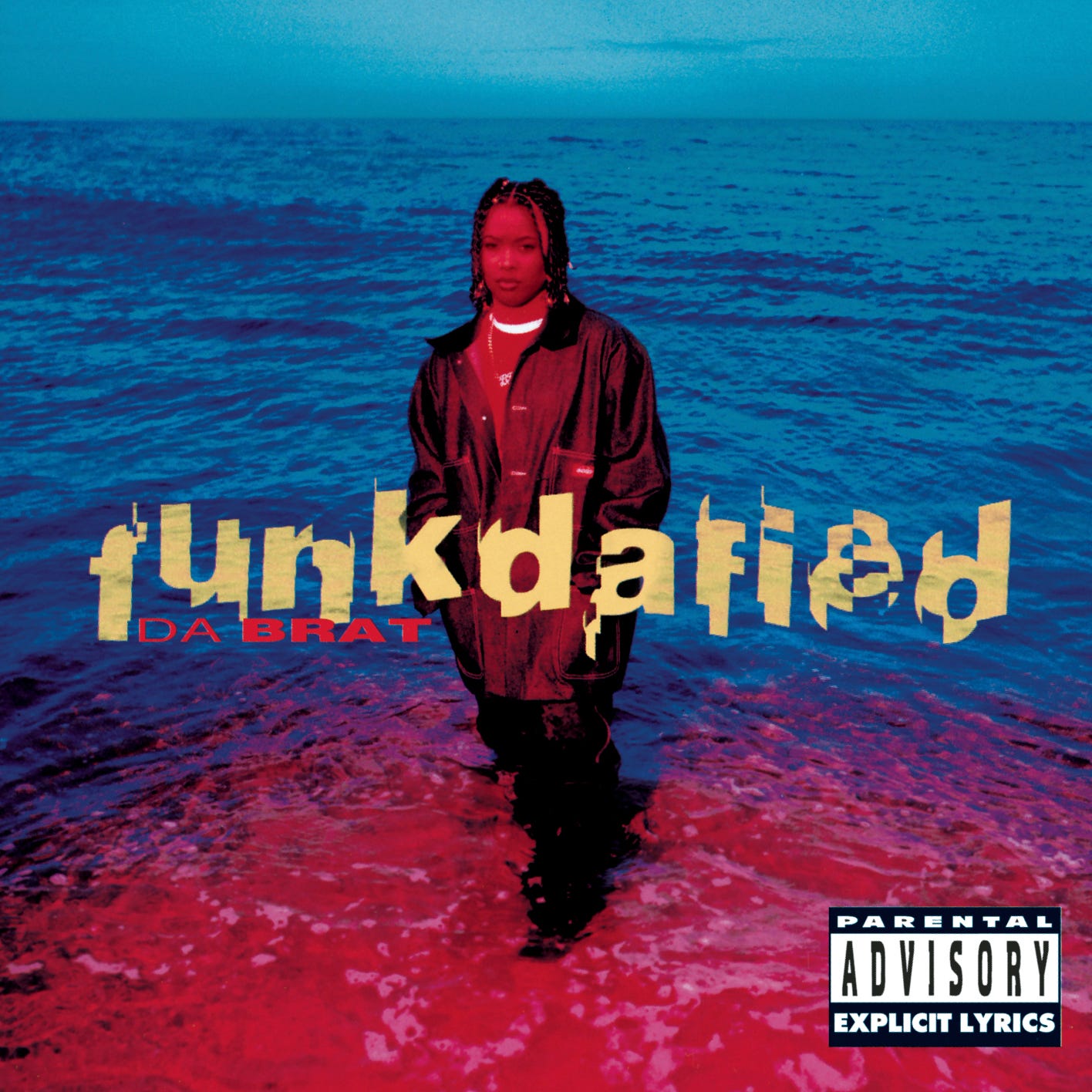

Da Brat, Funkdafied

The first solo platinum record by a female rapper was Funkdafied. This success arose from the alliance of two people from cities then on the fringes of rap, but soon to become central. Shawntae Harris, aka Da Brat (the brat, the bad kid), came from Chicago. There, she won a local rap contest sponsored by Yo! MTV Raps caught Kris Kross's attention. Through those two teenagers, who had just found success themselves, she met their producer, Jermaine Dupri, based in Atlanta. He took her under his wing and signed her to his label, So So Def. To ensure their first album’s success, however, the rapper and the producer looked beyond their own cities: they drew inspiration from California. In 1992 and 1993, that state defined the rules of rap via its g-funk style, and Da Brat followed the route already traced by that subgenre’s main star, Snoop Doggy Dogg. She borrowed his style with her braids and baggy clothes. She echoed his flow. She seized upon Dr. Dre’s “rat-tat-tat-tat,” transforming it into “brat-tat-tat-tat.” And she embraced the g-funk themes, portraying herself as a rowdy bad girl on “Da Shit Ya Can’t Fuc Wit,” “Ain’t No Thang,” and “Give It 2 You” (she did not have to fake it: known for her hot temper, Da Brat would become famous for various assaults).

The rapper, a party-lover, expressed her taste for having fun on “Mind Blowin’” and for weed on “Fire It Up.” On the production side, the influence also came from the same place. As the title Funkdafied announced, Jermaine Dupri used the funk sounds of the 1970s and 1980s—Funkadelic, the Isley Brothers, and Kool & The Gang. Sometimes, he even sampled artists from that scene, such as The D.O.C. and Snoop Dogg. His music, like theirs, was smooth, melodic, funky, warm, and quick to pull out sirens (“Come and Get Some”). Thanks to all that, Da Brat was perfectly in tune with the times, for a while the most popular female rapper in America, and her record sold over a million copies. However, trends changed at lightning speed in 1990s rap, and with Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown’s rise, Da Brat, by the time of her third album, Unrestricted, shelved her rebellious tomboy persona in favor of a sexier look.

Also check out: Anuthatantrum (1996), Unrestricted (2000)

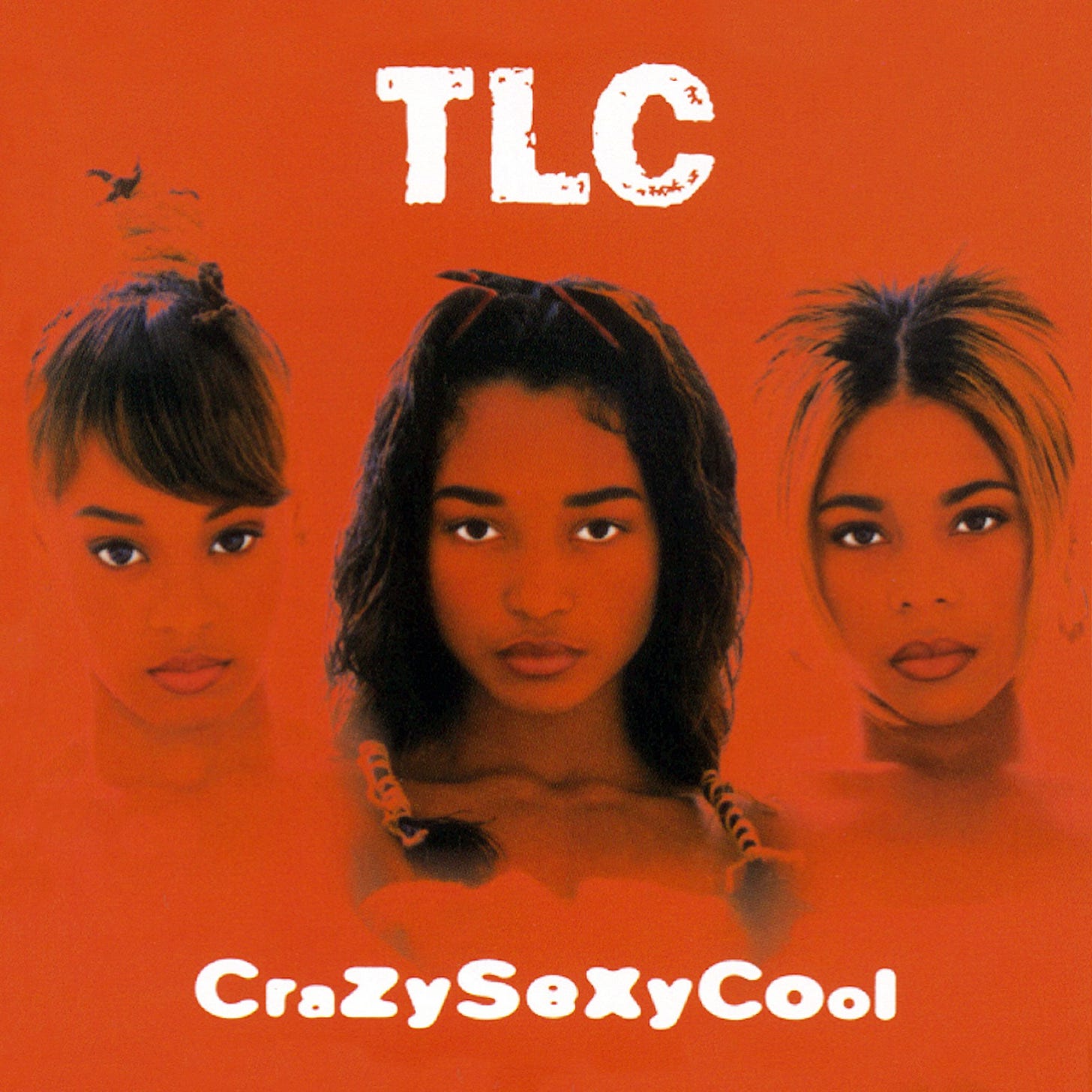

TLC, CrazySexyCool

CrazySexyCool is not a hip-hop album. However, this record—still the bestselling female group album after that of their contemporaries, the Spice Girls (14 million copies sold worldwide)—was important in hip-hop history. It exemplified a major trend in African-American music: the ever-greater convergence of rap and R&B. The trio evolved in an environment that straddled these two genres, with Jermaine Dupri, who had already brought success to the teenagers Kris Kross, the rapper Da Brat, and the R&B quartet Xscape, at its center. Another essential factor was the involvement of a handful of artists from the Dungeon Family collective, which would soon make Atlanta the center of rap: the producers of Organized Noize, who helped create the single “Waterfalls”; Cee-Lo Green (Goodie Mob and Gnarls Barkley), who contributed backing vocals on that same track; and André 3000 of OutKast, on “Sumthin’ Wicked This Way Comes. Though the three girls—who began their career with an overtly hip-hop image—headed in another direction on this album, they retained a cheekiness closer to rap than to an R&B still largely steeped in sentimentality.

On “Creep” and “Kick Your Game,” two more big hits, these three women—who had become known for promoting condoms—asserted their right to control their sex lives. The trio’s place in hip-hop was also connected to the presence of Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes. While the other two, Tionne “T-Boz” Watkins and Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas, worked in the traditional soul, funk, and R&B registers, the third member rapped. And her turbulent, edgy life aligned with the characteristic excesses of rap. It was well known that this young woman, who grew up surrounded by violence and addiction, swore in public, had several tattoos, and was the group’s “crazy” one. She grappled with alcoholism, and at the time of this album, she had a stormy relationship with football player Andre Rison, going so far as to set fire to their house. More troubles and excesses followed, up until a 2002 car accident in Honduras claimed her life. As an epitaph, the lyrics she wrote for “Waterfalls,” one of her great musical contributions, were engraved on her coffin.

Also check out: Ooooooohhh… On the TLC Tip (1992), FanMail (1999)

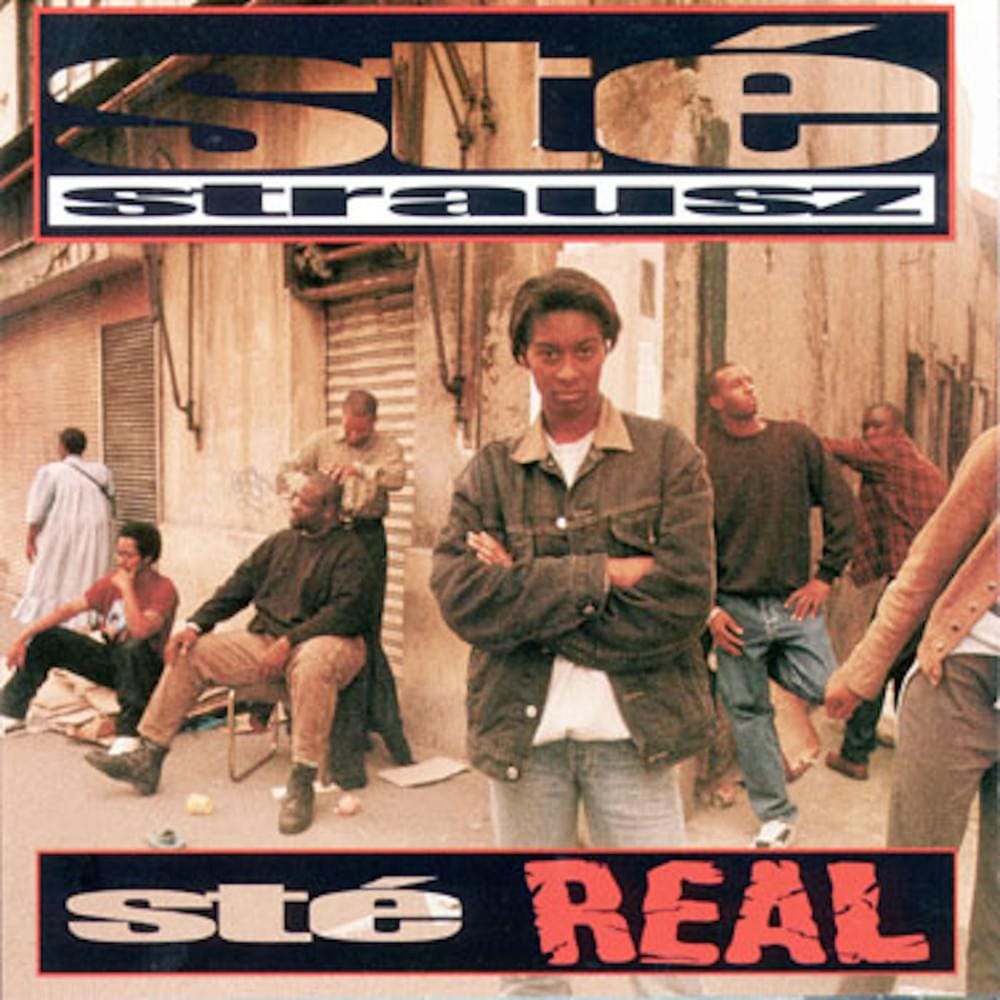

Sté Strausz, Sté REAL

Born in Vitry-sur-Seine, Stéphanie Quinol was from a Guadeloupean family, some of whose other members also played music. Her father was a DJ, and one cousin had been a rapper in the Mafia Underground. Thanks to him, she joined the Val-de-Marne rap scene, becoming the protégé of Little, one of that region’s pioneering groups. In fact, she owed her stage name to one of its members, Sulee B, who introduced her as “the good-looking woman in (Levi) Strauss.” In 1994, with their help, while she was only sixteen or seventeen, she released an EP whose standout feature was its adaptation of the West Coast sound to the French language. This release sounded more Californian than ever. Sirens, funky guitars, rounded bass lines, cinematic production, melodic synthesizers—all the hallmarks of g-funk were there. Tracks like “Met play (G Mix),” “Yo boom!” and “Née gangsta” [“Born gangsta”] were as potent as their American counterparts. And to complete the package, the rapper delivered a brash voice, full of the pride and confidence of a gangster. Nevertheless, it was indeed French rap.

As aggressive as the style might be and as colorful as the words sometimes got, it was far from the outrageousness and amorality of the Californians. Most of the tracks boiled down to classic ego trips and defending “real hip-hop,” as the title of the project implied. In “Trop dur pour un seul homme” [“Too Hard for One Man”], Sté Strausz asserted her identity as a woman, making it clear that she definitely should not be confused with a “byatch.” The track “Née gangsta,” where she claimed to have grown up in an environment conducive to crime, ended with a moral note: even if one is conditioned to become a bad boy (or girl), it is better to make music than to fall into delinquency. With this project, Sté Strausz found success in French rap. Following it, she gained a place on the La Haine soundtrack and on the compilations Génération Rap and Hostile Hip Hop. In 1998, she released her first album, Ma génération. Later, motherhood and a day job pulled her somewhat away from rap, but she did not entirely vanish. In 2010, she co-authored Fly Girls, a book about women in French hip-hop. Nevertheless, this American-flavored Sté REAL remained the high point of her career, bursting with youthful cheekiness and energy.

Also check out: Ma génération (1998)

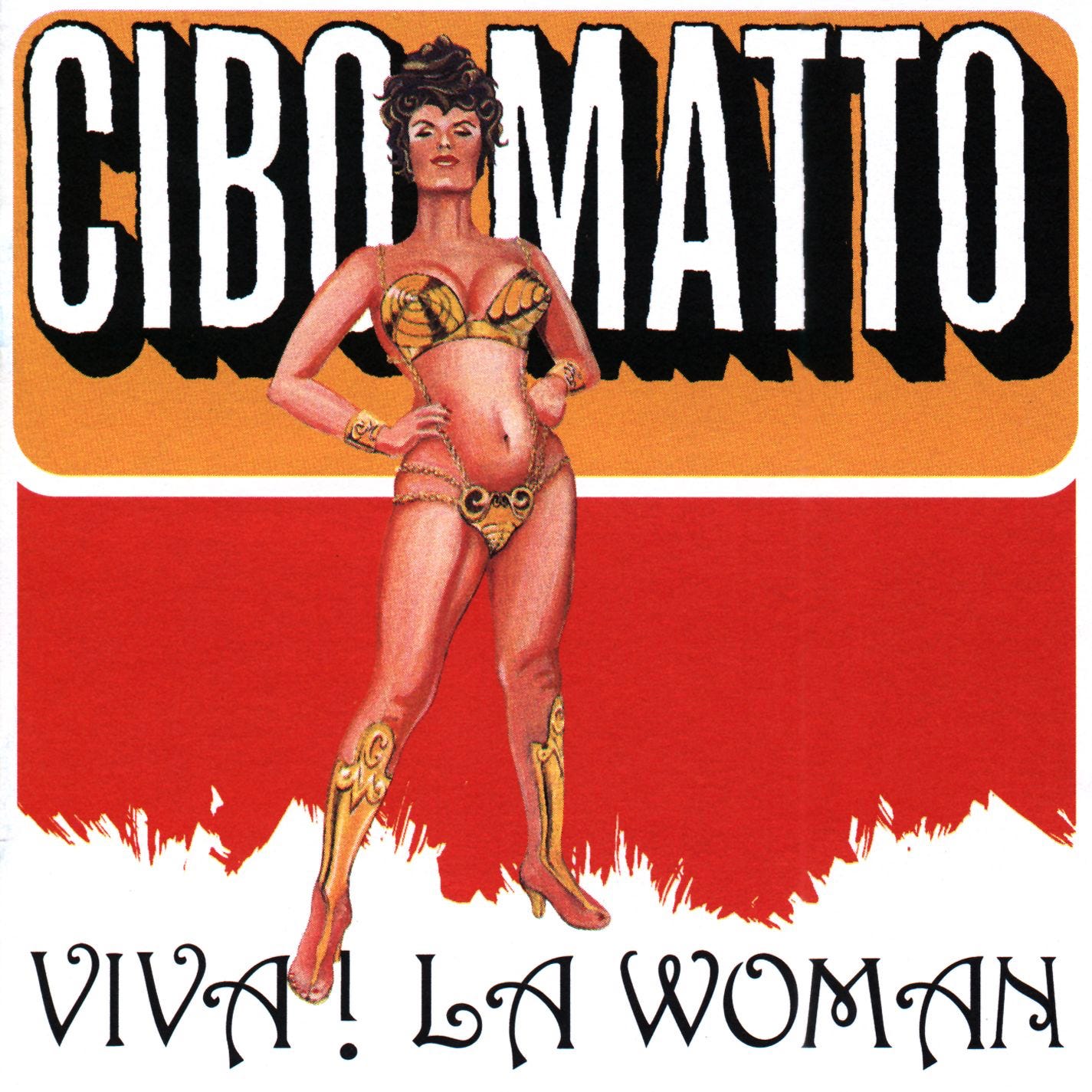

Cibo Matto, Viva! LA Woman

From the beginnings of hip-hop, New York has always produced an arty and cosmopolitan musical elite that, while not occupying the center of the rap scene, mingles with it and draws inspiration from it. And it has often included women. The most striking examples are Tina Weymouth of Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club and Debbie Harry of Blondie. Both came from the punk and new wave scene that, in the early eighties, helped popularize an emerging hip-hop. But long afterward, in the same place, others persisted in this kind of blend—one foot in rap, the other outside—and sometimes excelled at it. That was the case with Cibo Matto.

This duo with an Italian name, formed by Yuka Honda and Miho Hatori, two Japanese Americans, first stood out in a noise-rock vein, and it belonged to a sort of international bohemian musical elite that dabbled in everything. Honda was, for a time, the partner of Sean Lennon, the son of the Beatles and Yoko Ono (he would later join Cibo Matto), and Hatori would later become part of Gorillaz. Formally, however, on this first album, what the two women offer is definitely hip-hop, even if they make it take an unusual path. Their favorite theme is not so much manifested by its cryptic reference to The Doors’ LA Woman album, but rather in the very name of the duo, which can be translated roughly as “food-crazy.” With titles like “Apple,” “Beef Jerky,” “Sugar Water,” “White Pepper Ice Cream,” “Birthday Cake,” “Know Your Chicken,” “The Candy Man,” “Le pain perdu,” “Artichoke,” it’s all about food.

It’s a single theme but infinitely varied, leading as much to humorous scenes as to sensual metaphors. The music also plays with contrasts. It moves from retro moments to a purely hip-hop contemporaneity. The main language is English, but one can catch a few words of Japanese, Italian, and French. A salty-sweet album, showcasing a mutant and colorful hip-hop, Viva! LA Woman compiles atmospheric moments with a trip-hop essence, even easy listening, and bursts of punk fury, with Miho Hatori, the duo’s rapper and singer, capable of just as many mischievous murmurs as raging yells. Cibo Matto displays a kitsch radicalism that is often characteristic of Japanese pop music, adapted in this case to a rap context, making them nothing less than delicious and totally endearing.

Also check out: Cibo Matto (2006)

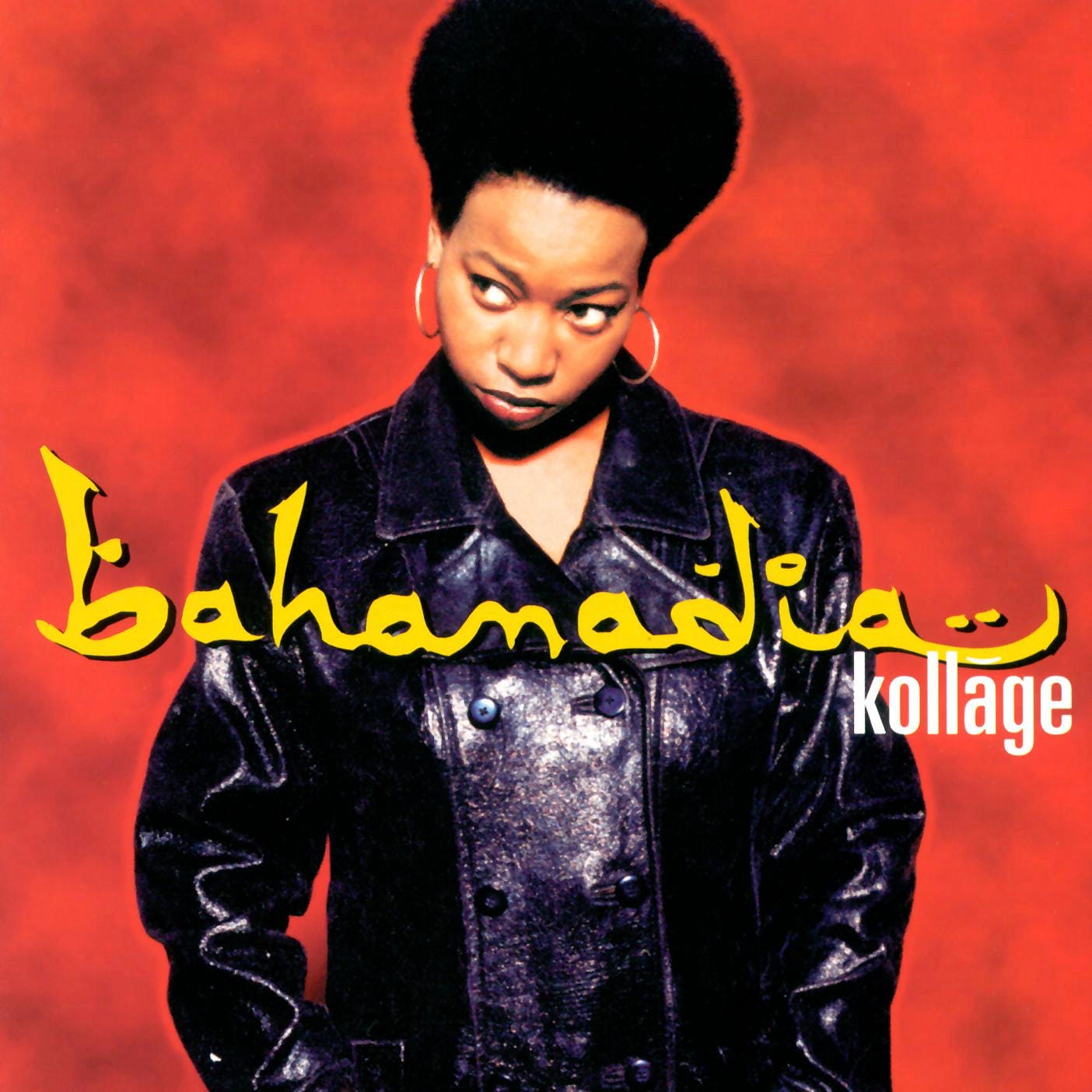

Bahamadia, Kollage

In 1996, Bahamadia already belonged to an older generation of rappers. She was then thirty years old, a venerable age to release a first rap album. In her hometown of Philadelphia, she had been part of the hip-hop scene since the early eighties. Initially a DJ, she eventually took the mic, following the example of female MCs of the time, notably Lady B, her local role model. But she had to wait for the following decade before, with Guru’s support, making a name for herself outside her home base. The Gang Starr rapper had her contribute to the second installment of his jazz and hip-hop fusion project, Jazzmatazz, and he helped her sign a contract with Chrysalis, through which she finally released this Kollage. Around the same time, she became the muse of the Lyricist Lounge nights and, through her radio show, sponsored an underground scene that was then developing in reaction to mainstream rap’s evolution. In many respects, Bahamadia embodied this school that some would soon label as that of the backpackers. She championed hip-hop that was open to other music (collaborating at the time with a number of English artists such as Morcheeba, The Brand New Heavies, and Roni Size—respectively trip-hop, acid jazz, and drum ’n’ bass aficionados) but one that was also purist, intellectual, and keen to preserve its heritage. Kollage naturally fit this trend.

Right from the outset, playing on the names of various rappers, “WordPlay” underlined Bahamadia’s respect for hip-hop heritage as well as the importance she attached to wordplay. In her low, deep, distinctive voice, the rapper highlighted creativity on a track called “Innovation.” She didn’t forget the scene that had birthed her, paying homage to Philadelphia on the excellent single “Uknowhowwedu,” and inviting Black Thought and Malik B of The Roots to guest on “Da Jawn.” Finally, she emphasized her female voice on “True Honey Buns,” as she criticized a groupie friend, and on “3 Tha Hard Way,” when she invited K-Swift and Mecca Starr, two other female rappers, to express themselves alongside her. To top it all off, the music on this album, produced among others by Da Beatminerz, DJ Premier, and Guru, extended the East Coast rap of the early nineties with its jazzy sounds, scratches, and boom-bap dominance. Kollage was a swan song of refined rap, the culmination of a first hip-hop generation that had reached adulthood, soon to be shaken up by younger rappers less concerned with artistic purity.

Also check out: BB Queen (2000)

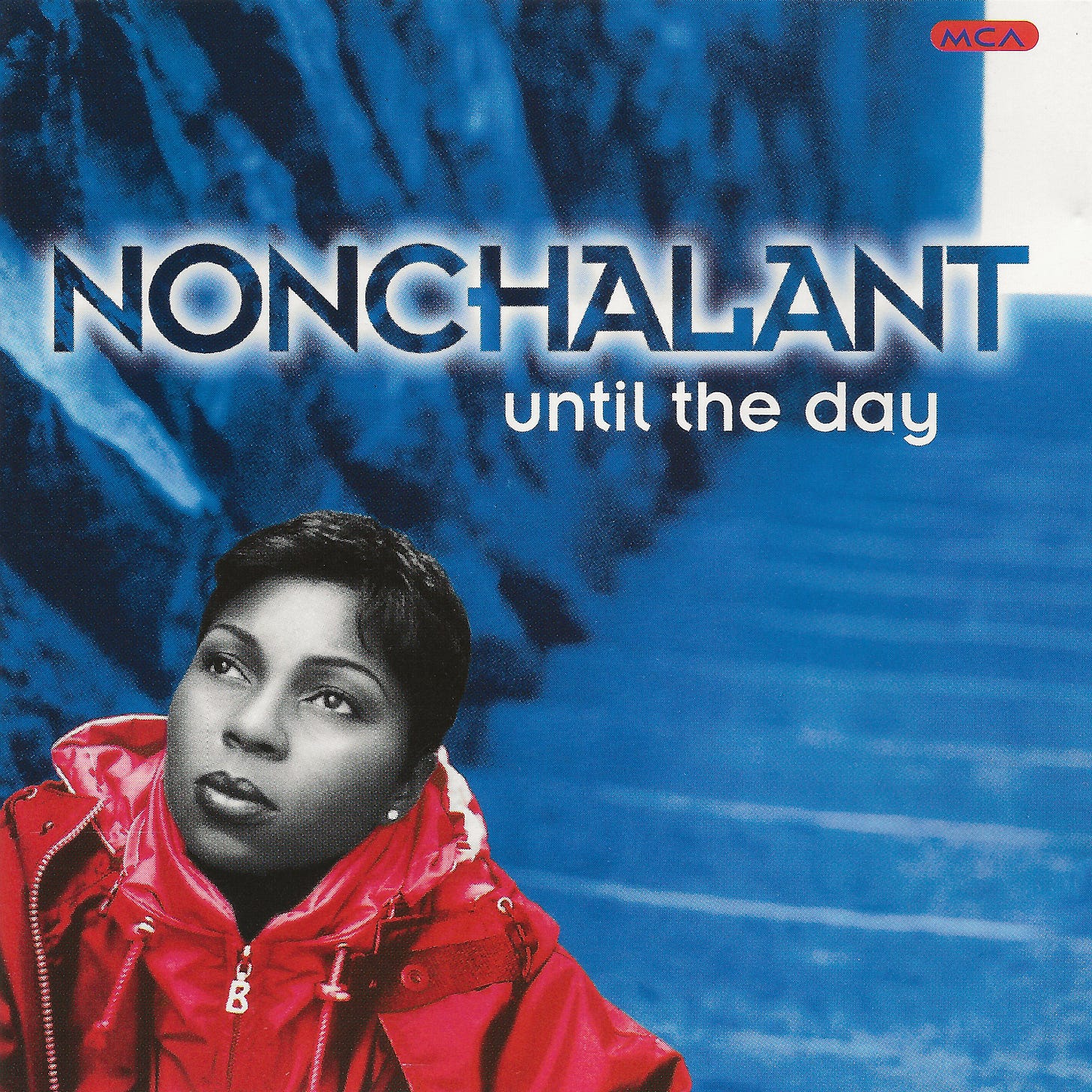

Nonchalant, Until the Day

Washington, early 1990s. Crack has a firm grip on the streets at the city’s edges. When dealing goes on at dawn, it’s scary waiting at the bus stop. “Five in the morning, where are you?” rapper Nonchalant asked in 1996. “Outside on the corner,” came the reply. If you want to historically contextualize police violence against people of color, you shouldn’t just jump from Martin Luther King and the ’60s riots straight to George Floyd in 2020; you should listen to Nonchalant. A lot happened in between. Tonya Pointer, a.k.a. Nonchalant, calls out everyone equally. She dislikes how pitiful drug dealers vanish into crime stats without anyone digging into the (politically intended) causes of their actions. But she also objects to criminals getting swept into illegal activity and basically giving up on themselves through self-pity, self-devaluation, and passivity.

At one point, she raps quite explicitly that it all begins with using ghetto slang. She herself chooses a generally understandable level of speech without any sociolect: no slang, barely any profanity, no foreign words, no pretentious jokes—just a fairly elevated everyday language. She phrases things so neutrally that her message can penetrate any social setting. For Nonchalant, a pivotal point on Until the Day is that the people in her hood aren’t “Black bros” she automatically feels connected to—they’re simply people doing what they do. It’s that simple. Wrong is still wrong, even when it’s committed by people you’d like to help. She structures her album thematically: corrupt and complacent cops, organized crime, illegal gun possession, robberies, broken-into cars, everyday racism, lack of education and a failing school system, drugs, alcohol, fast food, the role of women in the hood, empowerment, and the hope for a bit of love for others and for oneself. There’s a lot in there.

“5 O’Clock” was definitely no fluke. Some other tunes on the album might have captured the zeitgeist even more, and practically every track had the potential to chart. For its era—1996—Tanya Pointer mostly sounded like contemporary boom bap. In hindsight, Nonchalant points out that back then, that style wasn’t common in Washington, where go-go was the main sound. Communication with the outside world was still slow. Pure boom bap rarely broke into the charts. The funk-soaked “Crab Rappers,” the gospel-pop hook of the title track “Until the Day,” and the R&B-inflected “It’s All Love” and “Lookin’ Good to Me” probably had the best shot at further success.

Nonchalant might not have won many fans in the capital with her controversial statements about public safety and her detailed portrayal of outlying areas riddled with crack, coke, and crystal, alongside lazy, cowardly uniformed officers. But she was pretty much on the mark with her lyrics. Commercially and culturally, she was a phenomenon, selling gold-level records and making female rap popular in Europe. As of 2020, though, this lone album was missing from Spotify, Shazam, iTunes, Amazon, Bandcamp, SoundCloud, and Deezer—even though she was a role model. Once again, Nonchalant shows that some music genres once had a chance for gender equality, only to lose it, regressing into the imbalance and gold-chain macho posturing of the 50 Cent era.

In 2021, Nonchalant secured the digital rights to her planned 1997 follow-up album For All Non-Believers and finally released it worldwide on Spotify. This woman has so much talent that one of those rare, incredible late-career comebacks—like what happened with Chaka Khan—seems possible. Hopefully, she’ll find a label that appreciates her true value. Her only official album ends with a track called “Thank You,” and all we can do is say thanks right back: thank you, Non, for this music and for the lesson on how to pack an entire record with social critique while still keeping it gripping.

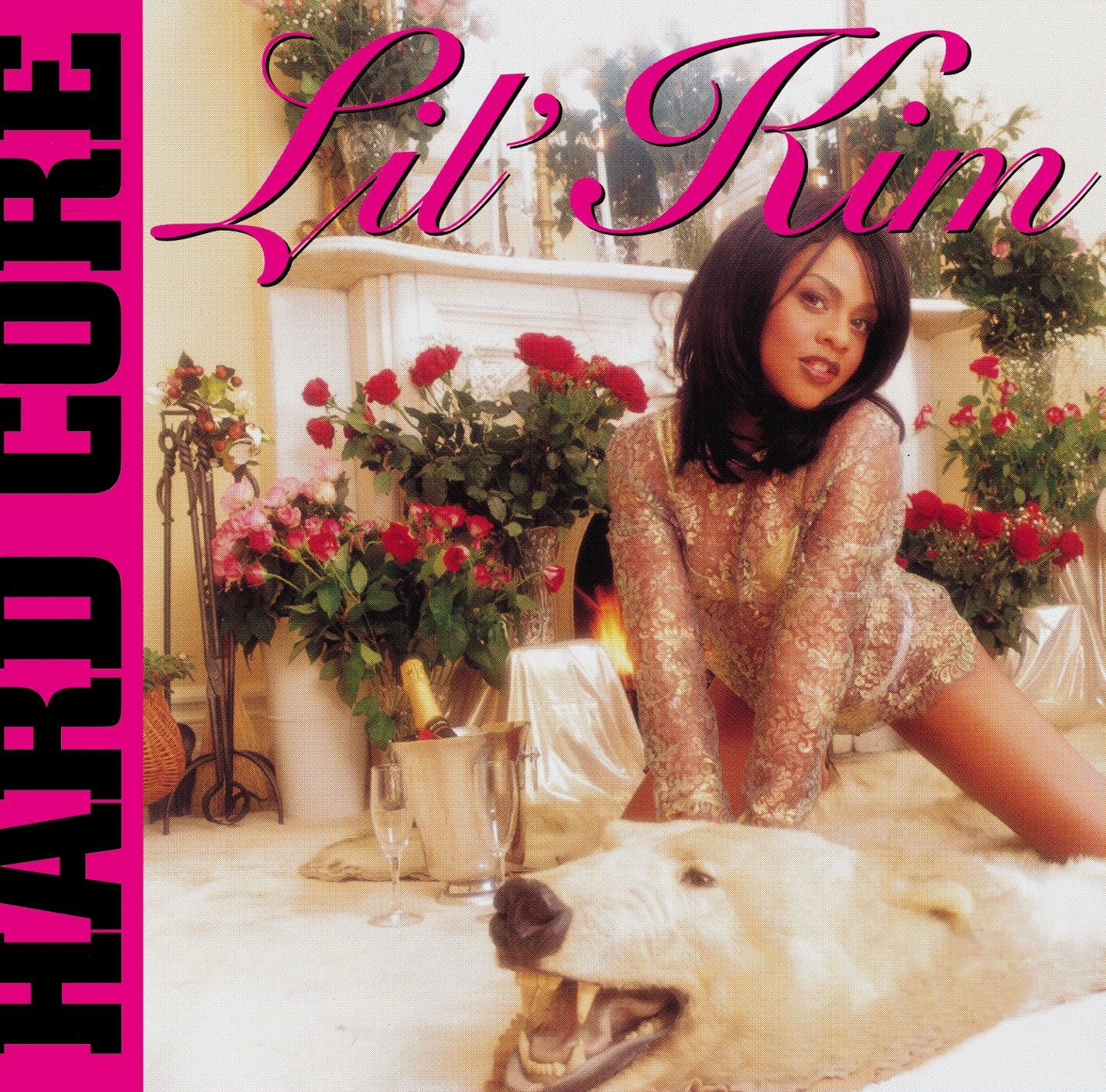

Lil’ Kim, Hard Core

Hard Core is not necessarily the best female rap album. It might not even be Lil’ Kim’s best; The Naked Truth, the one she released ten years later during a prison sentence, challenges it for the title. But it is her most important. It was a historic turning point. Certainly, before Kimberly Jones, other female rappers had demonstrated verbal prowess on par with the boys. Others had also played the sexy card. But few, in that vein, went as far. Indeed, as its title indicates, Hard Core is highly pornographic. Right from the first track, the rapper takes on the role of a porn actress. And a bit later, on the hit “Big Momma Thang,” featuring JAY-Z, she brazenly declares her taste for fellatio. Provocative, desirable, open to any sexual adventure, Lil’ Kim had enough to horrify certain feminists, who saw her submitting to every male fantasy. It’s true that she was, in part, the creation of a man. She owed a lot to Biggie whose mistress she had been, and who wrote much of her lyrics. And her album, in which she also extolled her taste for diamonds and luxury brands, fed into that hedonistic, nouveau-riche imagery that Biggie and his partner Puff Daddy—both featured here—were then steering rap toward.

However, it is too simplistic to reduce Lil’ Kim to a mere sex object. Because on Hard Core, in truth, she has full control of her sexuality: on “Dreams,” she shares her own fantasies (sleeping with the male R&B stars); on “Spend A Little Doe,” she defends her right to physical love; on “We Don’t Need It,” she places her desires on equal footing with those of the men from the Junior M.A.F.I.A. collective, as they jointly proclaim their love of every variation of oral sex. And then, more importantly, there is “Not Tonight,” a track where the young woman orders men to satisfy her need for cunnilingus. An anthem for women’s sexual liberation, this song has a second version featuring the top female rappers of the moment (Angie Martinez, Da Brat, Missy Elliott, and Left Eye). Hard Core unshackled women’s discourse on sexuality like never before. After this wildly successful album, Lil’ Kim’s career would have a few ups and many downs (prison, and a delirious spree of plastic surgery), but she changed the game for female rap forever: her hypersexual, “bad bitch” stance, yet in full control of her body and her desires, would become the norm.

Also check out: The Notorious K.I.M. (2000), La Bella Mafia (2003), The Naked Truth (2005)

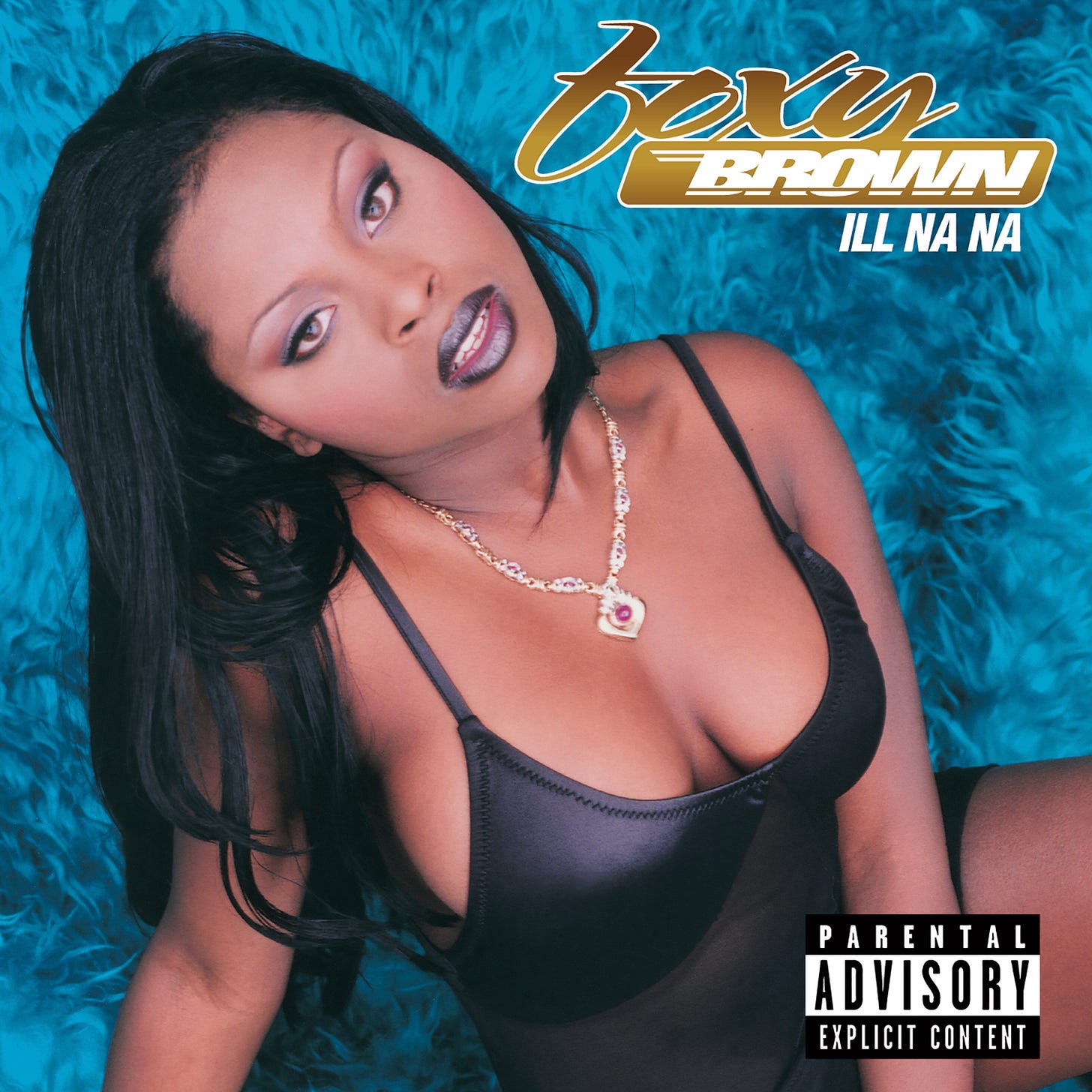

Foxy Brown, Ill Na Na

Released one week after Hard Core, Ill Na Na is, in some ways, its twin. Like her future rival, Inga Marchand (this young woman of Trinidadian heritage’s real name, before adopting that of a blaxploitation film heroine) belonged to a prestigious collective of New York rappers—in her case, The Firm, alongside Nas, AZ, and Nature. Her mic skills were on par with those of her male partners. Like Lil’ Kim, thanks in part to her deal with the Def Jam label, she achieved dazzling success with this first album, selling several million copies. Also like Lil’ Kim, Foxy Brown laid her body out as an offering on the cover and played the erotic card. The “na na” in the title refers to her vagina in local slang (short for “vagina”), that intimate part whose excellence she extolled on the eponymous track, alongside Method Man. Like the other great female rapper of 1996, however, she did not limit herself to the status of a sexual object. On the track “Ill Na Na,” she also presented herself as a liberated woman, abandoning her family in pursuit of her right to party all night. Foxy Brown had fun name-dropping luxury brands as well. And for the record, on the hit “I’ll Be,” this album also boasts a steamy duet with JAY-Z, a future rap mogul who was less well-known at the time than his two collaborators.

Ill Na Na, though, does not have the same exclusively pornographic stance as Hard Core. Despite Foxy Brown’s distinctiveness—she was a sexy rapper in a man’s world—this is, above all, a quintessential New York hip-hop album of that era. It features all the usual staples: a grounding in the local tradition, when the rapper referenced LL Cool J (“Foxy’s Bell”) or enlisted DJ Kid Capri (“Fox Boogie”); a street rap that is grim and dark, as heard in “The Promise,” with Havoc of Mobb Deep; the mafioso theme popular at the time, in “(Holy Matrimony) Letter To The Firm”; and early ventures into R&B, with Blackstreet and Teddy Riley on “Get Me Home,” then Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis on “No One’s.” While it was just as pivotal as Hard Core in steering female rappers toward the “bad bitch” model, Ill Na Na is not, like Hard Core, a manifesto. Most of all—and that is equally to its credit—it is a signature album of East Coast rap’s classic age.

Also check out: Chyna Doll (1999), Broken Silence (2001)

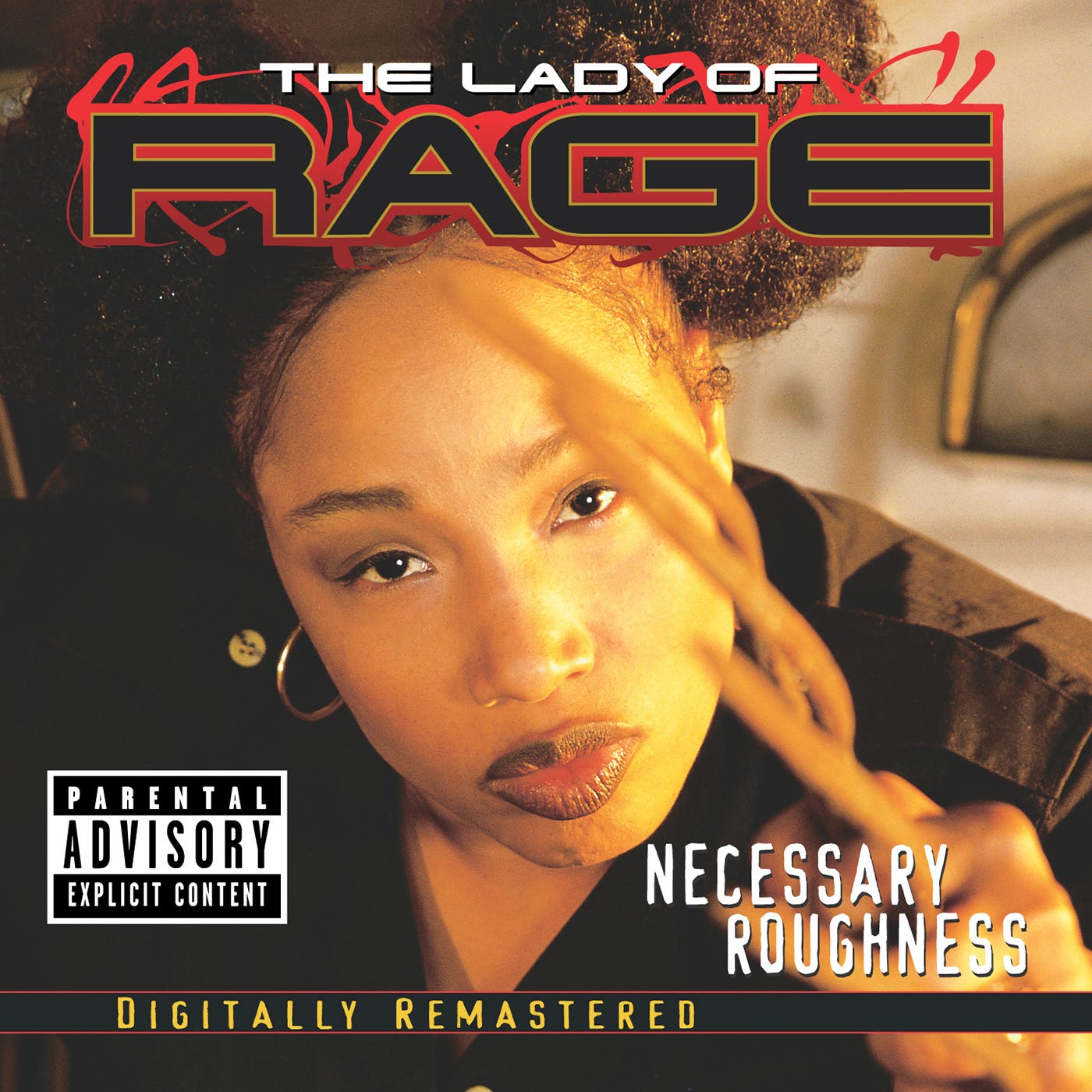

The Lady of Rage, Necessary Roughness

The Lady of Rage is not from California. Born in Virginia, she began in New York with the Outlaw Brothers, under the moniker Rockin’ Robin (based on her real name, Robin Allen), and then she collaborated with Chubb Rock. But she also worked with the Californian producers of the L.A. Posse, and it was through them that Dr. Dre discovered her and invited her to join his new label, Death Row. At the start of the nineties, the latter became the standard-bearer for West Coast gangsta rap and g-funk. Naturally, The Lady of Rage was destined to be its leading female figure. The rapper contributed to the legendary major albums of that era, The Chronic and Doggystyle, and her contribution to the Above the Rim soundtrack (a film featuring 2Pac), “Afro Puffs,” produced by Daz Dillinger and named after her trademark hairstyle (Afro pigtails), was a hit. But nothing is ever simple with Death Row, and its controversial boss, Suge Knight, preferred to invest in the duo Tha Dogg Pound, then in 2Pac, rather than in the female member of his team.

Consequently, her debut album, Necessary Roughness (which almost went by the name Eargasm), came out very late, in 1997, after 2Pac’s death and Dr. Dre’s departure from the label, and it smacked of the end of an era. Certainly, some important producers were involved in this record—Daz Dillinger, Easy Mo Bee, and DJ Premier—and The Lady of Rage sought to perpetuate the label’s glory days with the effective “Sho Shot,” the repentant bad-girl musings of “Confessions,” and “Rough Rugged & Raw,” which reunited what remained of the crew, Snoop Dogg and Daz. But something was missing. Probably because of the presence of New York producers, the music sounded more like East Coast boom bap than California g-funk. “Big Bad Lady,” “Super Supreme,” and the freestyle “Some Shit” were ego trips with a taste for complex words typical of New York, and “Get With Da Wickedness (Flow Like That)” harked back to the old-school era. It felt somewhat anachronistic, lacking originality. In the end, though, Necessary Roughness was not a bad album. It even enjoyed moderate success. But it did not live up to the status and promise of its creator, who would not release any more albums and instead focused on her acting career. With this record and its delayed release, The Lady of Rage suffered a sad reality: in hip-hop, investing in a female rapper has not always been a priority.

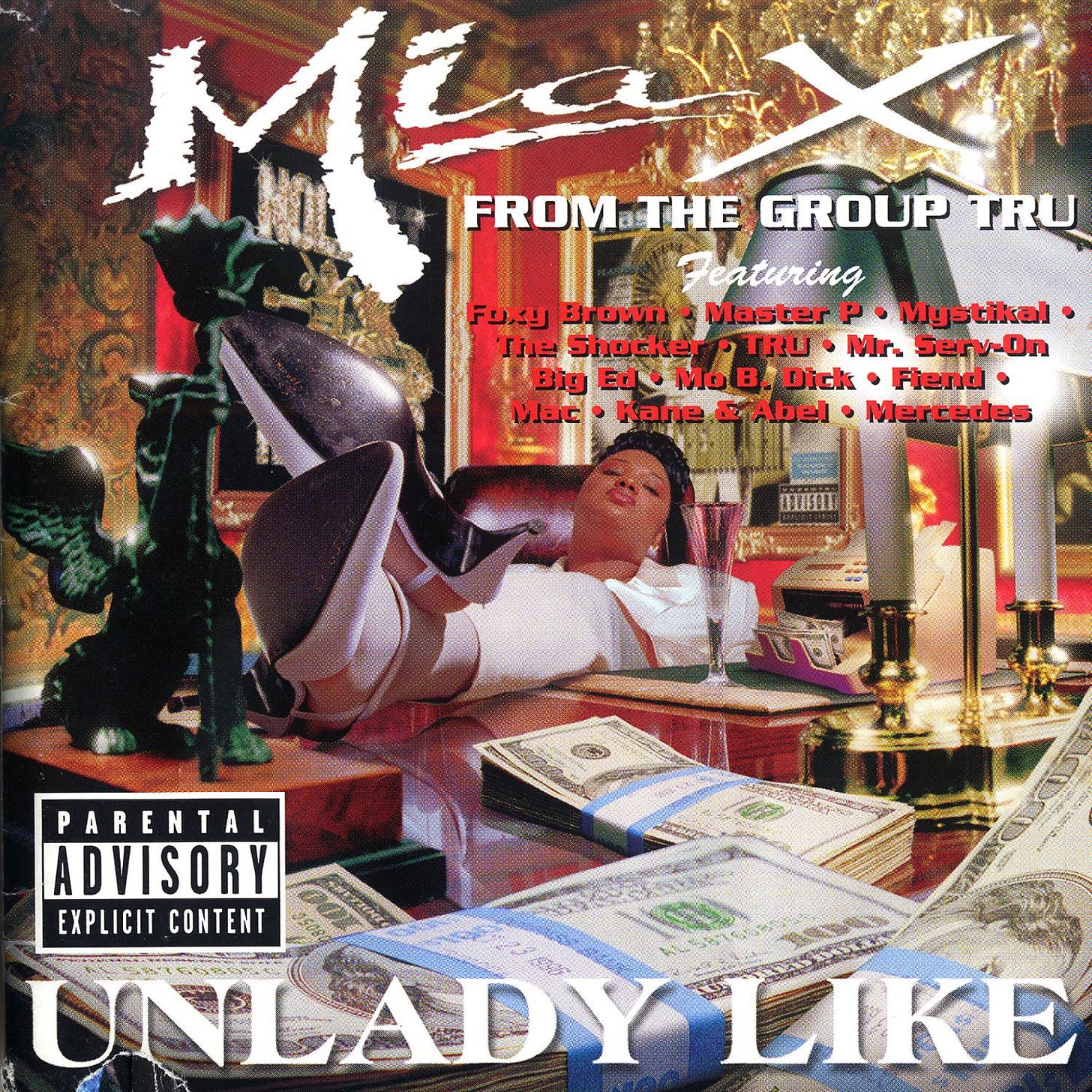

Mia X, Unlady Like

Mia X was not merely the token female of No Limit. Well before she joined up with Master P and he brought her into his label collective, Mia Young was already a notable figure in New Orleans. She had started rapping a decade earlier, while still a teenager, in New York Incorporated (a misleading name that for a long time made people believe she had lived on the East Coast), a group that also included another member destined for great success, producer Mannie Fresh. She later achieved a certain local fame, which was greatly amplified by No Limit’s ascent and, after it, the rise of Southern rap as a whole. While her first album, Good Girl Gone Bad, was a flop, her second one went gold. On the surface, Unlady Like does not differ much from the label’s other releases. Although it bore Mia X’s name, it was actually a collective project, produced by Master P and Beats By The Pound, with frequent appearances by the label’s star rappers—C-Murder, Silkk the Shocker, and Mystikal—starting with the very first track, “You Don’t Wanna Go 2 War.” Like all the others, it was a packed, chaotic record, where songs were stacked together haphazardly rather than following any logic—so much so that the one called “Intro” appeared squarely in the middle of the album.

Also, for most of the record, it was a loud, aggressive rap screamed at the top of one’s lungs, the sort of cartoonish and grotesque gangsta rap that horrified the label’s many critics but that also made its name. Mia X, however, left her clear feminine imprint on it when she invited her colleague Foxy Brown on “The Party Don’t Stop,” or when she put her own spin on Salt-N-Pepa’s “I’ll Take Your Man.” She also portrayed herself as the matriarch of the No Limit clan, its Big Mama, on “Mama’s Family,” or as its madam, on “Unlady Like,” where she reversed roles and claimed to profit from men’s prostitution. The rapper took on, in the name of women, all the excesses and indecencies of gangsta rap, thus invalidating the old charges of sexism leveled against it and showing its true face: that of a genre founded on a brazen assertion of self, with no inhibitions, no caution, and no limits—just as the label’s name suggests; that of a declaration of independence, even a feminine one, as when Mia X indulged in pornographic fantasies on “All N’s,” or when on “I Don’t Know Why,” she allowed herself to be moved by her feelings while still refusing to be at men’s mercy.

Also check out: Good Girl Gone Bad (1995), Mama Drama (1998)

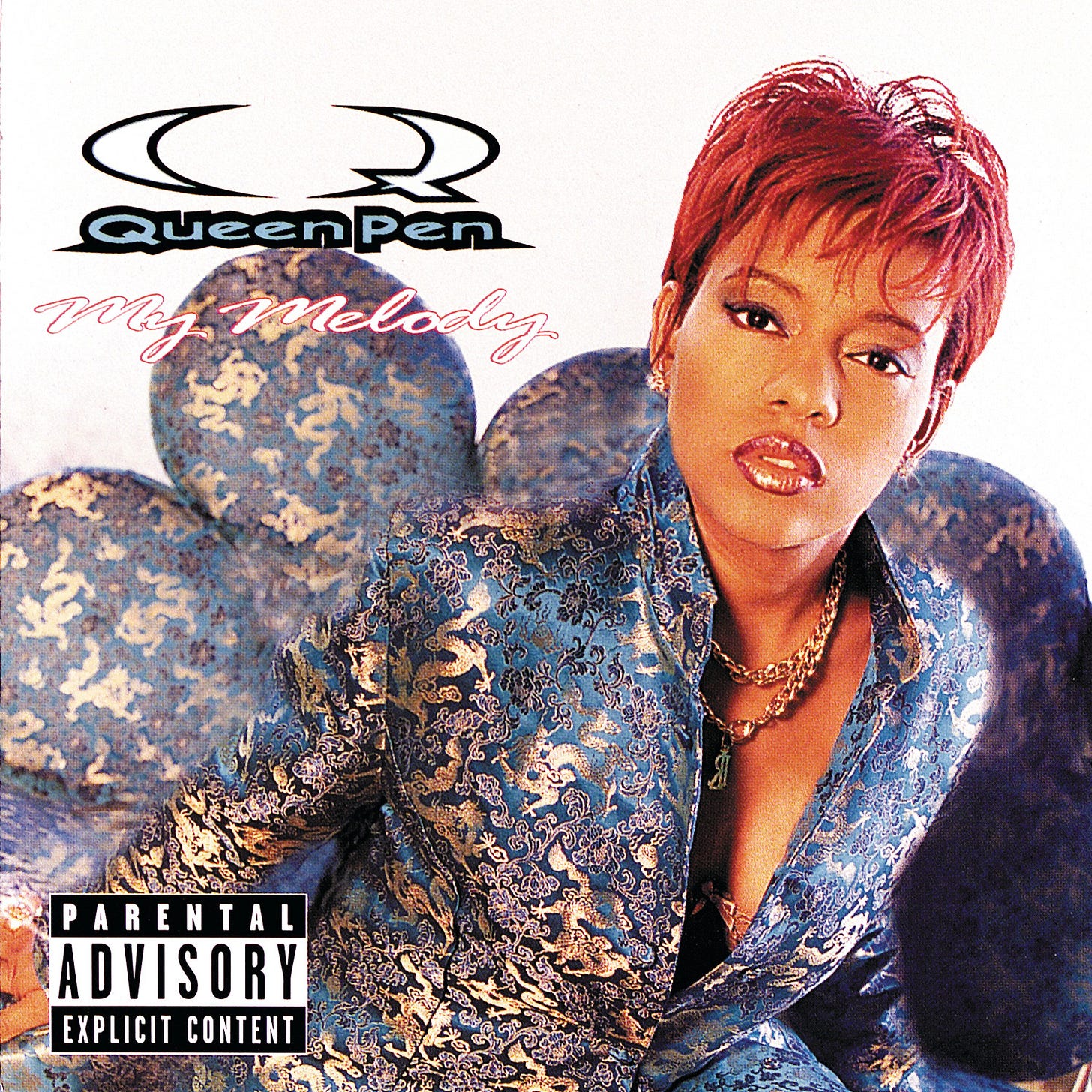

Queen Pen, My Melody

My Melody is not a rap masterpiece. It’s more of an honest album that clearly reflects its era. Like the Fugees did a year earlier, Queen Pen used it to bring rap closer to mainstream global pop by recycling or drawing inspiration from several of its standards. The track “It’s True,” for example, is based on Spandau Ballet’s “True”; “I’m Gon Blow Up” on the Isley Brothers’ “Voyage to Atlantis”; “All My Love” on Luther Vandross’s “Never Too Much,” and “Get Away” on Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight,” a track curiously known as one of the most sampled in rap history. This very pop color made sense for someone who was then the protégé of Teddy Riley, the mastermind behind the merging of hip-hop and R&B. After collaborating with his group Blackstreet on the single “No Diggity” (the very one that dethroned “Macarena” on the American charts), Queen Pen signed to Lil’ Man, the label of the man behind new jack swing, who was the main producer at work on My Melody. Naturally, therefore, it was a mainstream rap album, mixing upbeat ego trip (“Queen of the Click”), a track for the clubs (“Party Ain’t a Party”), and more or less happy love stories (“All My Love,” and “Get Away,” about a possessive lover).

Well-made and pleasant, this album was not enough to make Lynise Walters (her real name) a lasting star. Her sons later took over in music while she pursued writing novels. However, one of her tracks, “Girlfriend,” has significance in rap history. At first glance, this song, humorously poking fun at a man whose girlfriend has been taken away, is nothing out of the ordinary. Except that here, it’s about a homosexual relationship, still a taboo subject in rap at that time, and Queen Pen—supported by openly bisexual neo-soul singer Meshell Ndegeocello—plays the role of the seducer. This song, at once a critique of cheating men and a manifesto of sexual freedom, provoked the fury of less open-minded folks, notably Foxy Brown, who then attacked Queen Pen on “10% Dis” and “Talk to Me.” Pressed to disclose her own sexuality, Queen Pen was wise enough to refrain (it was only several years later that she would admit she was heterosexual), avoiding muddying a debate which, well before the wave of coming outs and LGBTQ+ rappers of the 2010s, continued to stir hip-hop for a long time.

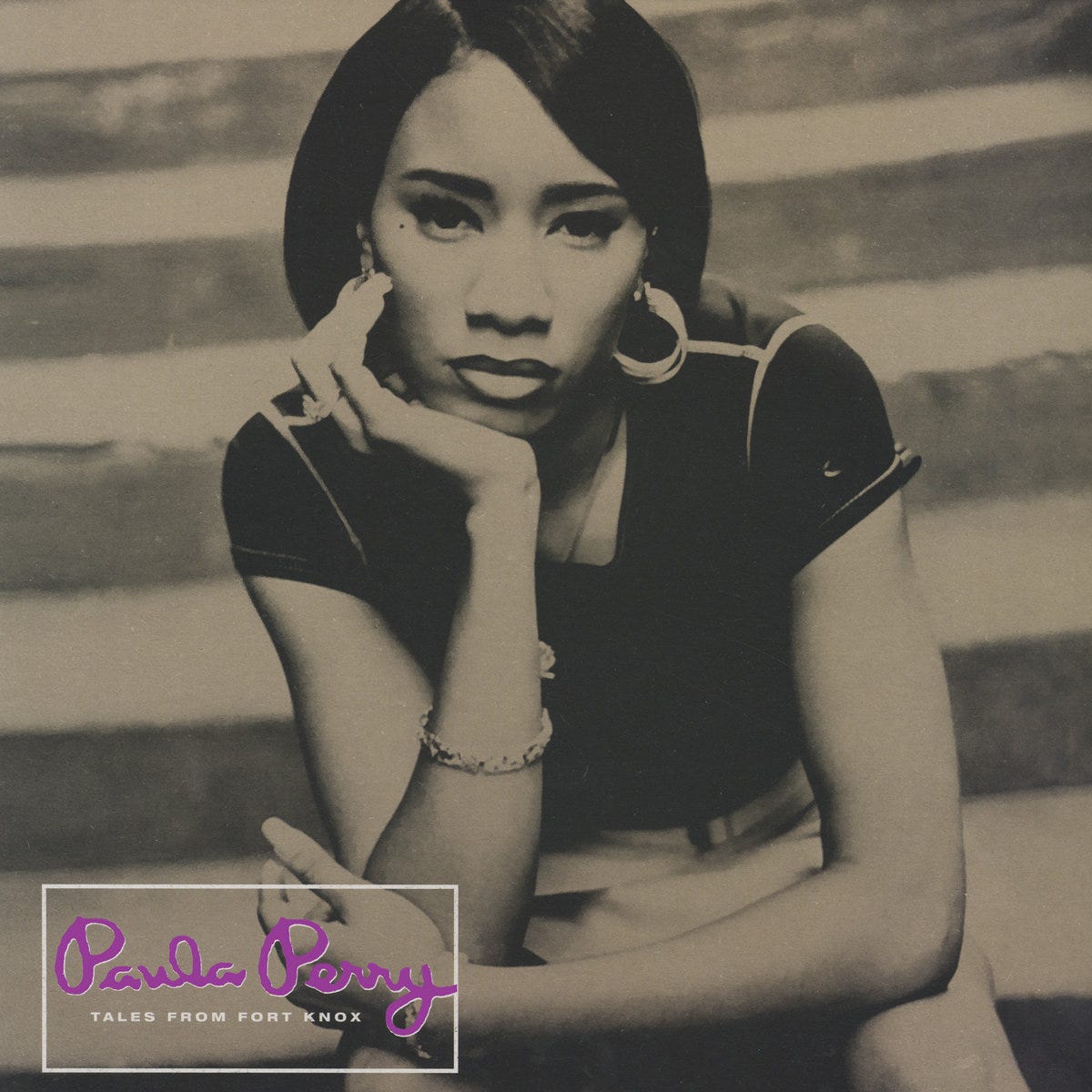

Paula Perry, Tales from Fort Knox

Paula Perry surfaced as a notable figure in New York’s hip-hop scene during the mid-1990s. She carved her place with the release of her debut album, Tales from Fort Knox, under the guidance of producer DJ Premier and her affiliation with the Masta Ace-associated crew, Masta Ace Incorporated. This project arrived in 1998, marking her entry into a male-dominated field with a collection of tracks that leaned heavily on gritty beats and sharp lyricism. A closer look at the album’s creation reveals a collaborative effort shaped by more than just Perry’s voice. DJ Premier, already a heavyweight in the rap production world, crafted the bulk of the instrumentals, lending his signature boom-bap sound to tracks like “Extra, Extra” and “Paula’s Jam.” Meanwhile, her ties to the crew brought in guest verses from the likes of Masta Ace (even the R&B features with Brian McKnight and Kelly Price), adding a layer of street credibility that amplified the album’s reach beyond her solo contributions.

Perry’s style echoed the raw energy of contemporaries like Onyx or Group Home, with its focus on hard-hitting rhymes and unpolished delivery over sparse, drum-driven production. Perry’s unapologetic presence as a woman in the mix set Tales from Fort Knox apart, tackling themes of survival and hustle without softening her edge. Including “Down to Die for This” and one of the most underappreciated posse cuts, “Six Pack,” showcased her ability to match the intensity of her male peers (although the latter is an all-out women’s barfest), flipping the script on gender expectations by diving into tales of loyalty and street life with a commanding tone. Later efforts, such as her work with Masta Ace on Sittin’ on Chrome, built on this foundation, reinforcing her reputation as a rapper who could hold her own. While not as sexually charged as some successors, Tales from Fort Knox laid down a blueprint for female MCs who favored authenticity over glamour, signaling a quiet shift in the genre’s lineup.

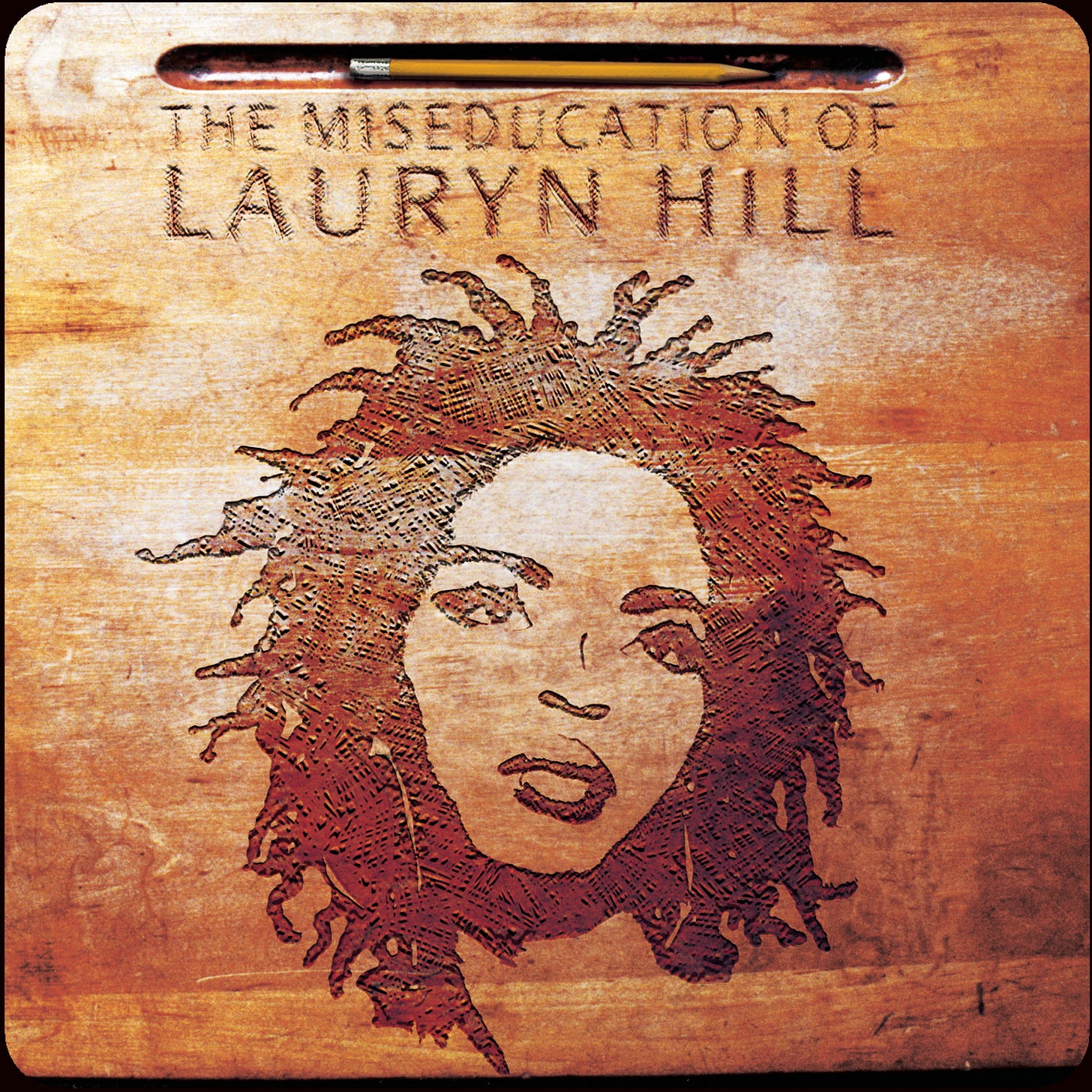

Ms. Lauryn Hill, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill

Aside from MTV Unplugged in 2002, Ms. Lauryn Hill has never released more than one solo album—but what an album! In 1998, two years after the success of The Score, the Fugees rapper returned on her own with a work that completed what, through her pop and reggae covers, she had begun doing with the group’s other two members: definitively erasing the line between rap and mainstream global pop and establishing that musical style permanently. The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill would even surpass the trio’s album, becoming a timeless classic. The rapper continued here to move away from rap’s gangsta themes and routines, tackling more conventional emotional topics with even greater force and heartbreak, as this album was recorded when she left Wyclef Jean for Rohan Marley, Bob Marley’s son, a new lover whose child she was already expecting (the child to whom she dedicated the track “To Zion”). A soul diva teleported into the rap era, she revisited the traditional themes of the great black music, speaking mostly about love’s joys and sorrows, about better days for the ghetto on “Everything Is Everything,” and even about God on “Final Hour.”

Musically, Ms. Lauryn Hill also pushed boundaries. Recorded partly in Jamaica’s Tuff Gong studio, with the Marley family nearby and with the support of musicians who would later criticize the rapper for not crediting them properly, she, like the Fugees, dipped into reggae and dancehall. Reconciling all forms of Black music, she blended in old doo-wop (the album’s first single took its name from that style) just as much as modern R&B, with a guest appearance by Mary J. Blige and the emerging nu-soul, with D’Angelo, who was soon to become one of its standard-bearers. Returning to her pre-rap passions, she frequently sang as well, infusing each text with her lovely rasp. The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill is an ultimate work. True to the message of “Superstar,” where she stated that music loses its spontaneity when it aims for success, Ms. Lauryn Hill has since gone almost silent. One of the most worshiped female rappers in hip-hop history now only makes headlines for her tantrums, her diva behavior, and the births of her many children.

Also check out: MTV Unplugged (2002)

Also recommended: Fugees, The Score (1996)

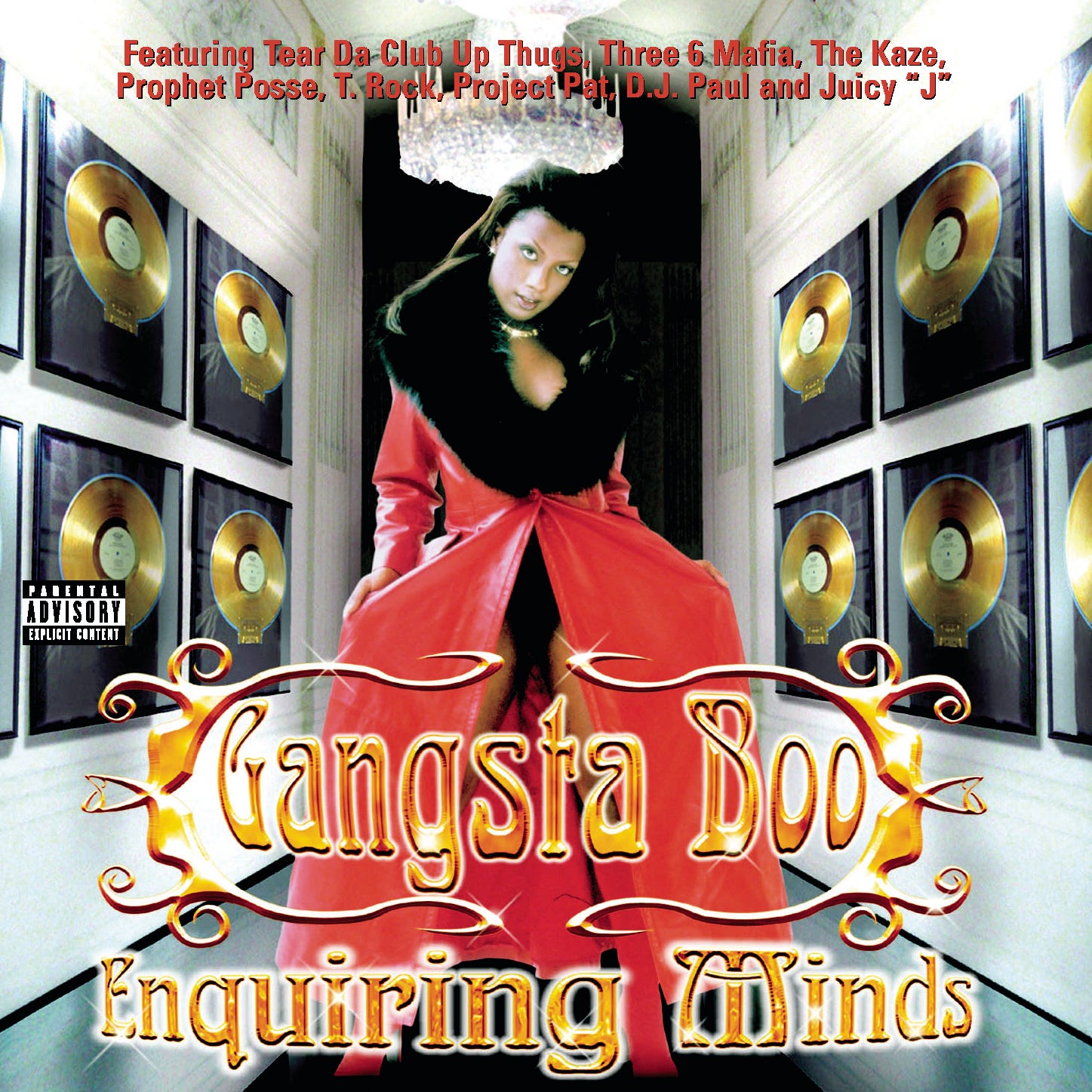

Gangsta Boo, Enquiring Minds

How can one be a girl in a group often deemed the most misogynistic in rap history? How to survive among people quick to objectify women, glorify strip clubs, and flirt dangerously with the theme of rape? Gangsta Boo addressed that question when she joined Three 6 Mafia at barely sixteen years old. She did it by keeping pace with them in violence and aggression—Juicy J, DJ Paul, Lord Infamous, and the others. She succeeded by piling on outrage, her female voice magnifying the impact of this historically influential group that would later be awarded an Oscar. And the wild spirit that Lola Mitchell brought to the group’s collective albums she continued on her own, with this debut opus—naturally produced by Juicy J and DJ Paul—that featured several members of Memphis’s Prophet Posse, the larger collective to which they all belonged.