The Handguide to Kendrick Lamar

From Compton storyteller to Pulitzer prize-winner to headlining one of the biggest events as a solo rapper, the first to do it. We give flowers to Kendrick Lamar Duckworth.

“It’s time to put Compton on the map,” it sounded in 1988 from the ranks of the Niggaz With Attitude. In 2011, years before the movie Straight Outta Compton made everyone and his mother an N.W.A. fan, this battle cry has long since echoed. However, Los Angeles’ most notorious neighborhood still has a lot to offer. Appearance: Kendrick Lamar was born on June 17, 1987. Encouraged by a teacher, he fell in love with creative writing and hip-hop lyricism, fascinated by rhymes and metaphors. This passion was cemented by pivotal moments in his childhood. Notably, at age 8, he watched hometown heroes Dr. Dre and Tupac Shakur film a music video in Compton, an experience that profoundly inspired him to pursue rap. By his teens, Kendrick had transformed these influences and observations into lyrical craft, seeing music as an escape and a means to make sense of the chaos around him.

As a 16-year-old known then by the moniker “K. Dot,” Lamar released his first mixtape, Y.H.N.I.C. (Hub City Threat: Minor of the Year), in 2003. The tape’s raw talent and honest storytelling created a local buzz beyond just Compton, and it earned the teenager a contract with the upstart independent label Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE). Over the next few years, K. Dot honed his skills on a string of underground mixtapes: Training Day (2005) showcased his dense wordplay, and a collaborative tape with Jay Rock in 2007 (No Sleep ’Til NYC) helped cement a new generation of West Coast talent. In 2008, Lamar joined forces with TDE labelmates Jay Rock, Ab-Soul, and ScHoolboy Q to form the collective Black Hippy, a crew intent on lyrical excellence and reinventing West Coast hip-hop. Together, they bounced ideas and guest features across each other’s projects, cultivating an alternative rap movement out of L.A.’s underbelly.

By 2009, after releasing the mixtape C4 (a tribute to Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter III), Lamar felt it was time to shed his alias and rap under his real name. “The name change was just me developing myself… I want people to know who I am as a person and what I represent,” he explained. This personal rebranding marked the end of “K. Dot” and the emergence of Kendrick Lamar as an authentic voice of his own. It was a pivotal maturation: he wasn’t just a kid spitting rhymes anymore, but a young man with a story—and message—uniquely his. This period also saw Lamar refining the socially conscious narratives and introspective tone that would define his music. Immersed in Compton’s realities and hip-hop’s rich history (from N.W.A. to Tupac), Kendrick was now armed with both the experiences and the crew to support his ascent. All he needed was the right project to break through.

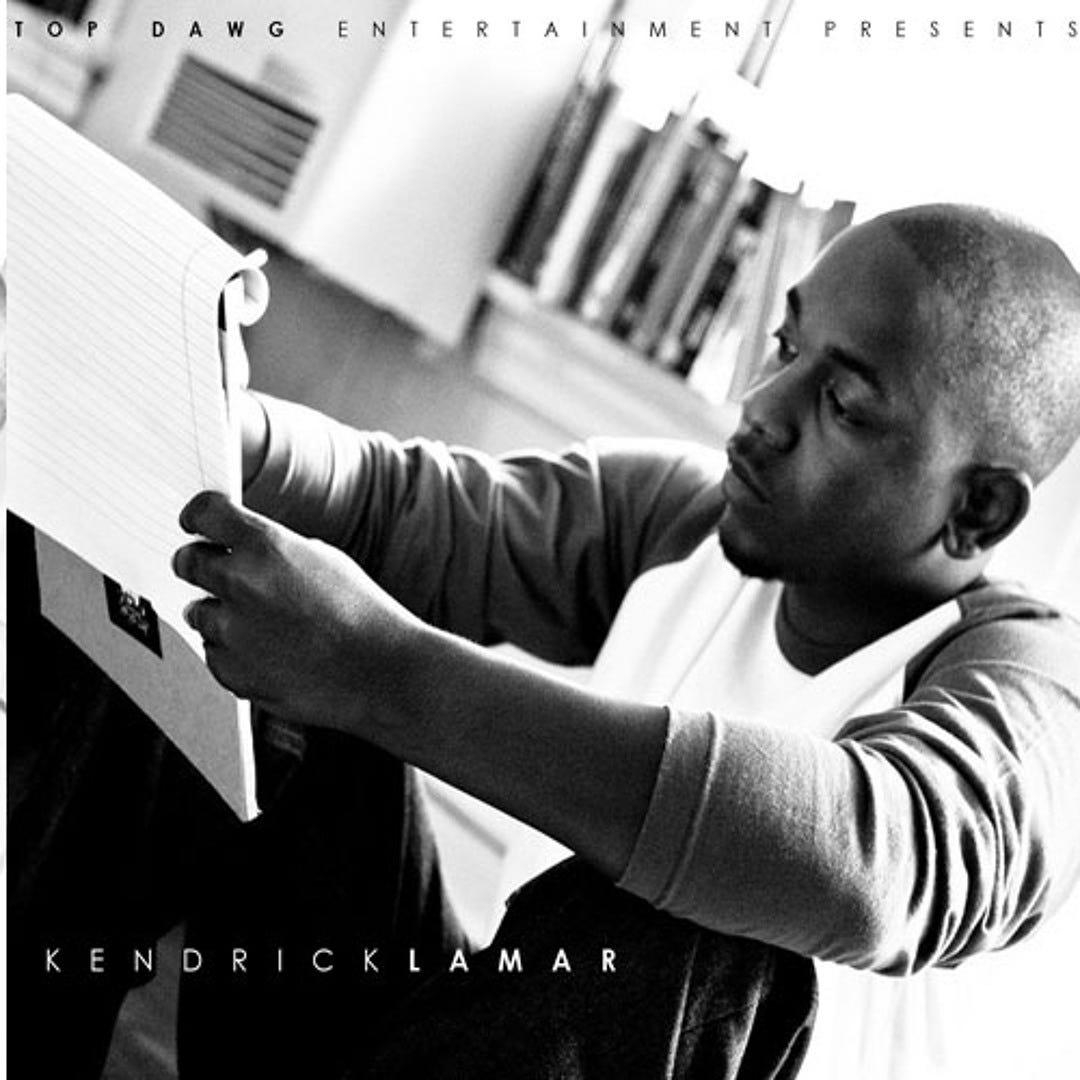

Kendrick Lamar EP (2009)

At the tail end of 2009, Kendrick Lamar released the self-titled Kendrick Lamar EP, a free project that served as a re-introduction to the world under his birth name. The EP’s production, handled by emerging talents like Sounwave and seasoned beatsmiths like Jake One and Q-Tip, provided a soulful backdrop for Kendrick’s nascent storytelling. It featured guest appearances from his TDE/Black Hippy comrades (Ab-Soul, Jay Rock, ScHoolboy Q) and hinted at concepts he would later explore in depth. Critics have since called the EP a “Rosetta Stone” for Kendrick’s career—noting that themes and even characters appearing briefly here would blossom in his later classics. Though modest in mainstream impact, the Kendrick Lamar EP restored buzz around the young MC after a lukewarm previous mixtape, proving he could craft cohesive songs rather than just freestyle over industry beats. It was the first real showcase of Lamar’s ability to mix poignant personal reflection with the sounds of L.A.’s underground, setting the stage for a run of groundbreaking releases. — B.O.

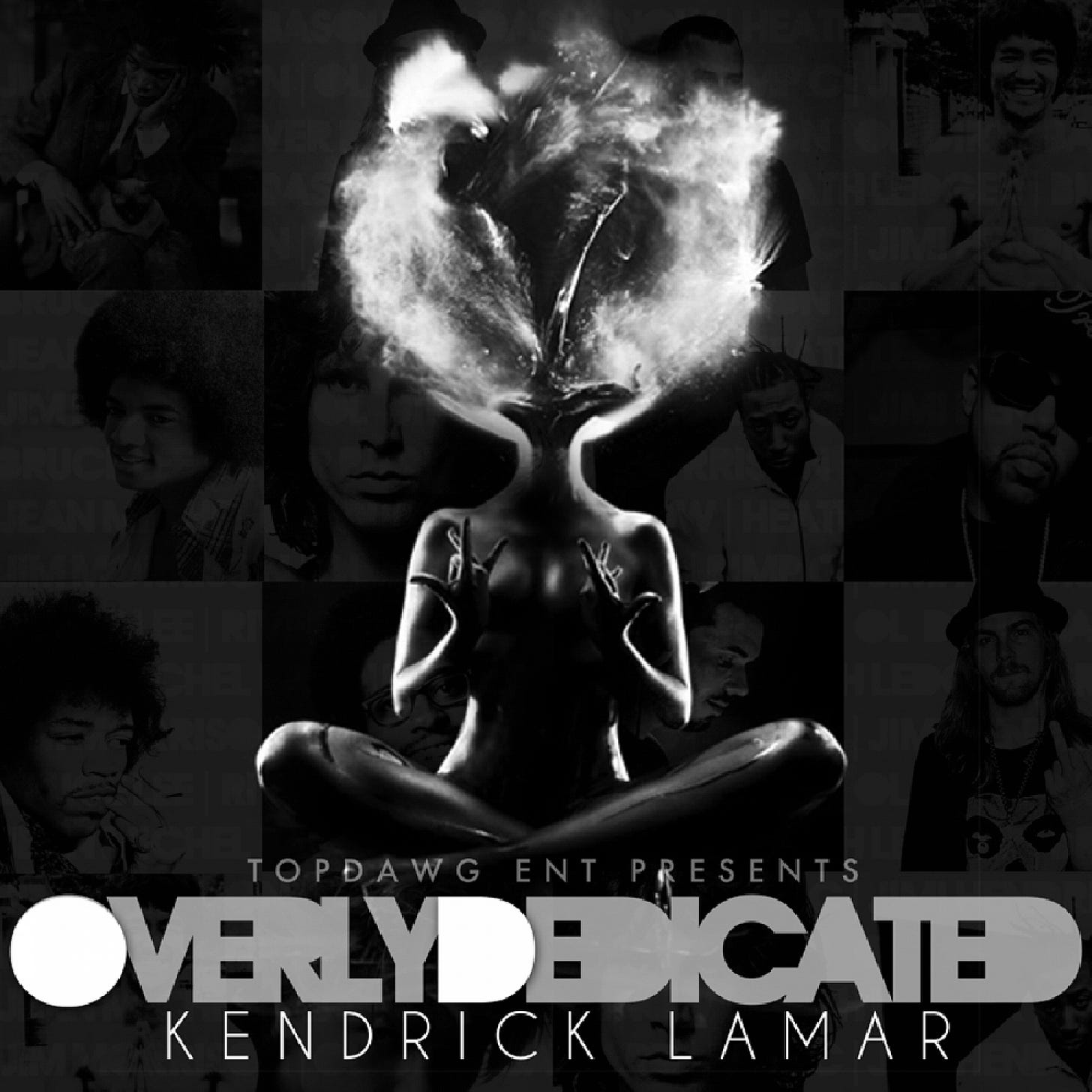

Overly Dedicated (2010)

In September 2010, Lamar delivered Overly Dedicated (often abbreviated O.D.), his fourth mixtape and the first under his real name. Overly Dedicated was a tipping point – the project that graduated him from a local hero to a rapper on the industry’s radar. Built on lush, moody production from TDE’s in-house team Digi+Phonics, the mixtape blended soulful hooks with hard truths. On “Ignorance Is Bliss,” for instance, Kendrick assumes the voice of a trigger-happy youth glorifying gang life, only to end each verse with the haunting refrain “ignorance is bliss,” revealing the self-aware irony. This complex storytelling impressed Dr. Dre, the West Coast super-producer who saw the song’s YouTube video and immediately wanted to work with Lamar. In fact, Dre reached out to mentor the young rapper after hearing that track, eventually inviting him to contribute writing to the long-mythologized Detox album. Overly Dedicated gained critical acclaim for its honest narratives and smooth execution – even veteran critic Robert Christgau graded it an A− and flagged songs like “Alien Girl,” “P&P 1.5,” and “Average Joe” as early examples of Lamar’s brilliance. The mixtape even cracked Billboard’s Heatseekers chart, a rare feat for an independent release, and signaled that Kendrick Lamar was overly dedicated to pushing hip-hop’s creative boundaries. — P

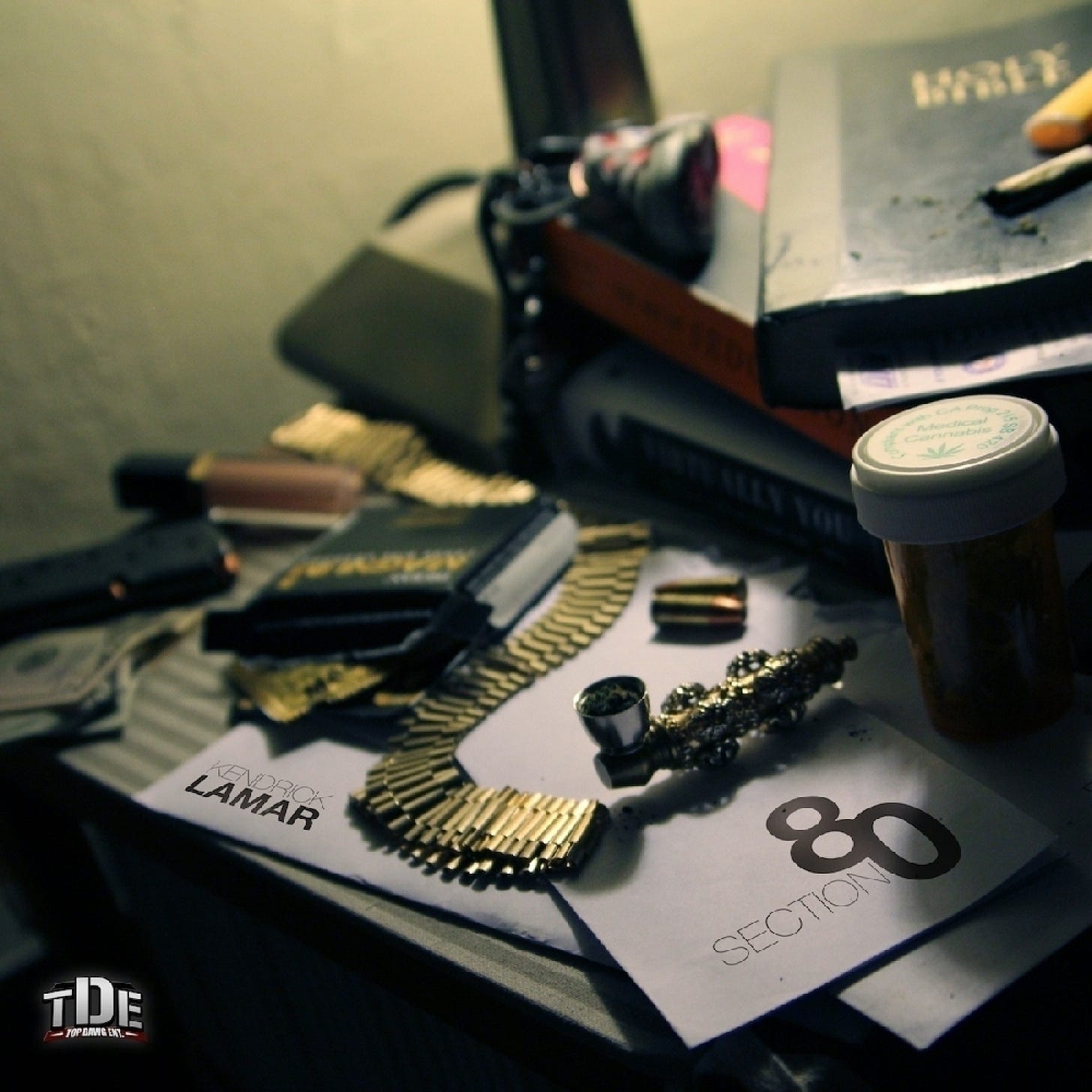

Section.80 (2011)

Buoyed by this momentum, Lamar released his official debut Section.80 in July 2011, exclusively on iTunes under Top Dawg Entertainment. Section.80 was a bold concept album that captured the voice of a generation born in the Reagan era, hence the title referencing those born in the 1980s. Over jazzy, “stripped-down” production and head-nodding boom-bap, Lamar tackled heavy themes: the fallout of the 1980s crack epidemic on inner-city youth, the numbness of a generation medicated by prescription pills, and the shadow of racism that loomed over his peers. “A.D.H.D.” explored young people’s dependence on drugs, while “Keisha’s Song (Her Pain)” told the tragic story of a sex worker caught in a cycle of abuse—showcasing Kendrick’s gift for empathetic storytelling. Notably, Section.80’s closing track “HiiiPoWeR,” produced by fellow rising star J. Cole, introduced a philosophy of self-empowerment and social awareness that Kendrick championed. With minimal promotion, the album still sold around 5,000 copies in its first week and eventually cracked the Billboard 200 at #113—a major achievement for an independent debut. Many recognized it as proof that Lamar was next up in hip-hop’s elite. In April 2017, years after its release, the album was certified Gold, underscoring its slow-burn impact and lasting relevance. Around this time, Kendrick’s lyricism and growing buzz led to a crowning moment: at a 2011 Los Angeles concert, West Coast legends Kurupt, Snoop Dogg, and The Game joined him on stage and literally passed the torch—with Snoop declaring, “You got the torch… it’s yours,” anointing Kendrick as the new king of West Coast rap. With Section.80 as his foundation, Kendrick Lamar had one foot in the underground and one stepping firmly into stardom, poised to take his place in rap’s pantheon. — P

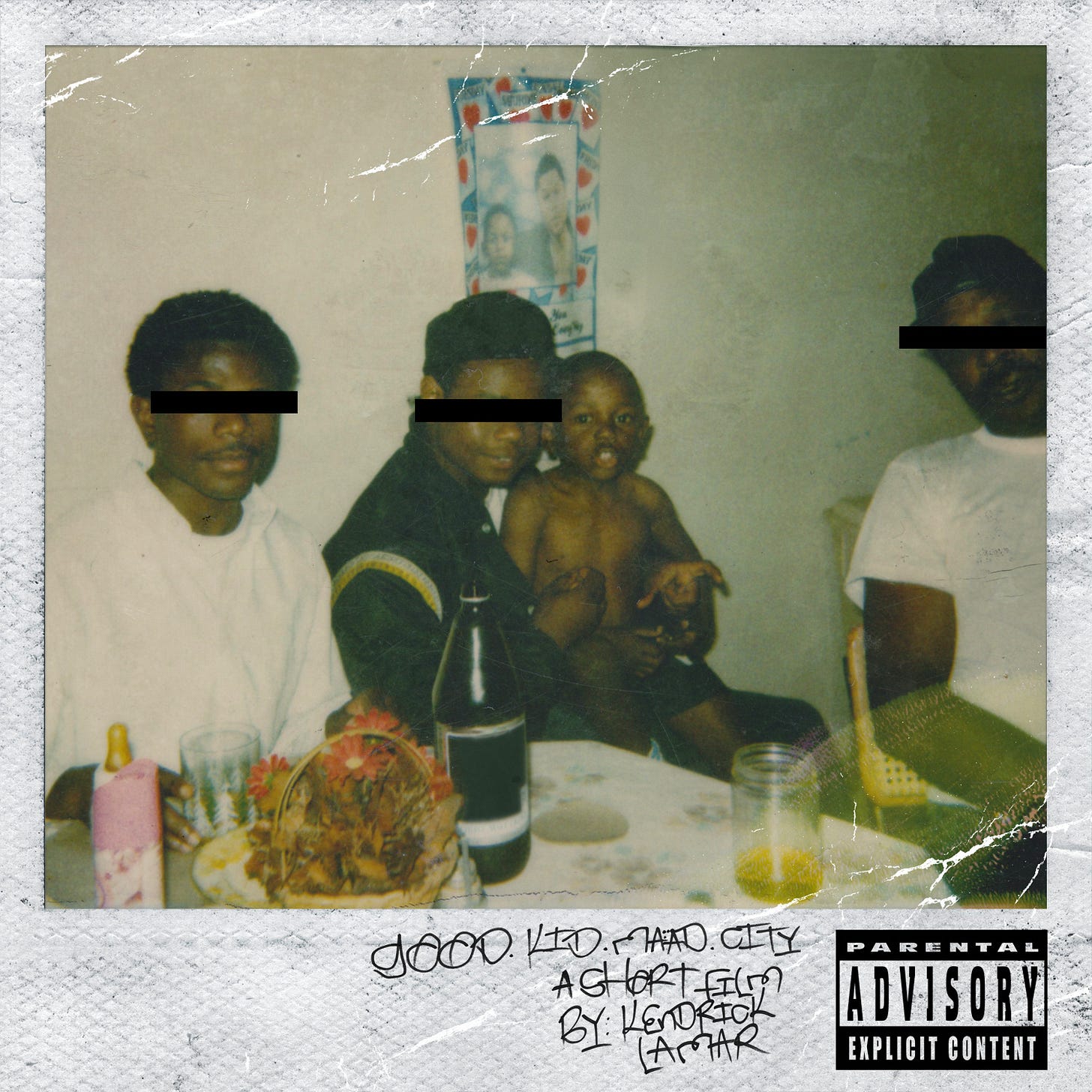

good kid, m.A.A.d city (2012)

By 2012, Kendrick Lamar was ready to fulfill the promise that his mixtapes and indie album had built. His major-label debut good kid, m.A.A.d city dropped in October 2012 on TDE/Aftermath/Interscope, and it was immediately lauded as a masterpiece of narrative hip-hop. Subtitled “A Short Film by Kendrick Lamar,” the album plays like an immersive coming-of-age movie on wax. Across its tracks, Lamar chronicles a day (and lifetime) in Compton through the eyes of his teenage self, weaving a nonlinear story about youthful innocence and the ever-present menace of gang culture. Through inventive skits—like his parents leaving voicemails asking for their van back or a group prayer said after a friend’s death—the narrative follows Kendrick (“K. Dot”) as a good-hearted kid navigating peer pressure, crime, and hope in a “mad” city. He introduces a cast of characters from Sherane (a teenage love interest who lures him into trouble) to his straight-laced mother and wayward friends, giving the album a novelistic scope. The storytelling is so vivid that listeners feel they’re in the backseat during “The Art of Peer Pressure” or standing beside Kendrick during the tragic drive-by in “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst.” Lamar’s lyrical technique on this record was equally masterful – he switched his flow and voice to portray different characters and emotions, rapping in double and triple-time bursts and layering internal rhymes throughout. These skills underscored that he was a storyteller, first and foremost, using rap not for braggadocio but as urban reportage.

This LP struck a brilliant balance between gritty and polished. Dr. Dre served as executive producer, and the beats ranged from atmospheric West Coast funk (the menacing stomp of “m.A.A.d city”) to lush soul (“Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe”). The album spawned hit singles that propelled Lamar further into the mainstream. “Swimming Pools (Drank),” a sleek but dark examination of alcohol culture, became a Top 20 hit on the Billboard Hot 100, its catchy chorus often mistaken for a party anthem despite the song’s underlying critique of binge drinking. “Poetic Justice,” built on a dreamy Janet Jackson sample, showcased Lamar’s ability to craft a radio-friendly love track without sacrificing lyrical complexity. Beyond the numbers, its impact on the culture was immediate—publications dubbed it an instant classic, and veteran artists from Nas to Snoop Dogg praised Lamar’s accomplishment. In fact, the album essentially fulfilled the prophecy made when Snoop had handed Kendrick the West Coast torch a year prior. With this record, Kendrick Lamar was no longer just the promising kid from Compton. He had arrived as a creative force rejuvenating the art of rap storytelling for a new generation. — B.O.

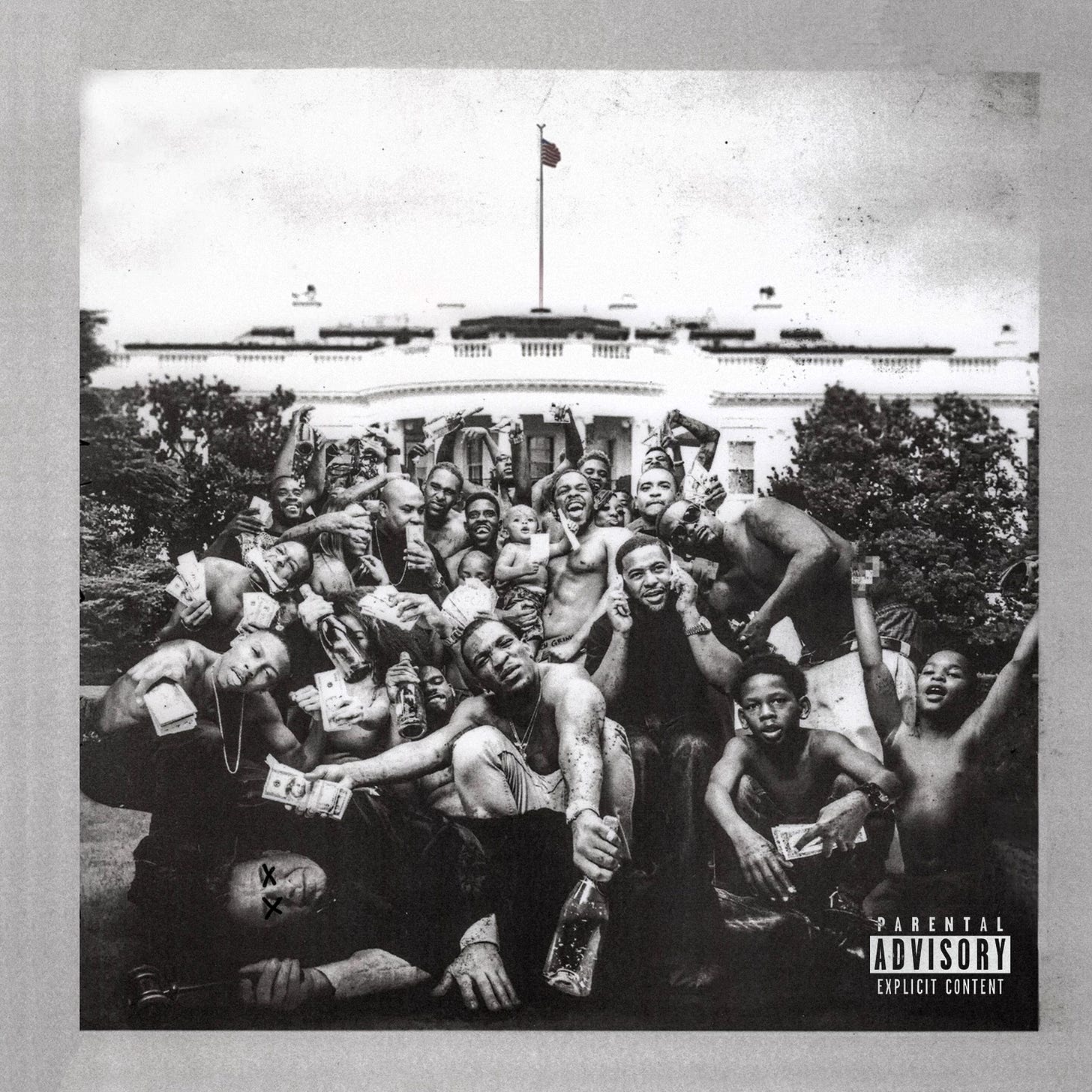

To Pimp a Butterfly (2015)

Faced with sky-high expectations after his breakout, Kendrick Lamar took a bold left turn with his next project. To Pimp a Butterfly was a radical departure from the sleek narratives of good kid – an avant-garde odyssey that fused hip-hop with jazz, funk, and spoken word poetry in a way rarely (if ever) heard on a mainstream rap album. Recorded in Los Angeles studios with a live band of virtuosos (bass wizard Thundercat, saxophonist Kamasi Washington, producers like Flying Lotus and Terrace Martin), the album drew on the rich musical lineage of black America. Its opening moments feature George Clinton, the godfather of P-Funk, and from there, the record flows through echoes of Miles Davis, Sly Stone, and Afrocentric ‘70s soul. Kendrick uses this eclectic soundscape to reflect on themes of race, power, depression, and resilience. If good kid was a tight screenplay about one city, To Pimp a Butterfly was an abstract canvas capturing the tumult of a nation and the psyche of an artist in the spotlight.

The album is dense with metaphors and messages. The title itself is a metaphor about metamorphosis and exploitation—“pimping,” a butterfly, represents how society can trap something beautiful (the soul, talent, or the black spirit) for its own gain. Throughout the album, Lamar reads bits of a spoken word poem that gradually unravels his internal struggle with fame and survivor’s guilt, addressing it in the final track to the ghost of Tupac Shakur in a fictional interview. Tracks like “u” bravely expose Kendrick’s personal battles with self-loathing and depression (with a harrowing delivery as if crying into the mic), while “The Blacker the Berry” is searingly militant, tackling racial hypocrisy. Yet, amid this heaviness, To Pimp a Butterfly also radiates pride and hope. The standout single “Alright,” produced by Pharrell Williams with an upbeat jazz tempo, offers a mantra of survival: “We gon’ be alright.” That song quickly transcended music—protesters across America chanted its chorus at Black Lives Matter rallies, making “Alright” an unofficial anthem of the movement against police brutality. As writer Marcus J. Moore noted, “Alright”’s long-lasting impact isn’t on the charts… it’s in the streets, chanted by the people for whom the song was made. Kendrick’s performance of “Alright” atop a swaying police car in the music video (and a gripping live rendition at the BET Awards) further solidified its place in protest music history.

When To Pimp a Butterfly was released, it debuted at #1 and shattered the notion of what a commercial rap album could sound like. Despite its experimental nature, it garnered widespread critical acclaim; many called it a masterpiece and drew comparisons to landmark works like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On for its fusion of art and politics. The album earned Kendrick 11 Grammy nominations (a record for a rap artist at the time) and took home five awards, including Best Rap Album. Notably, “Alright” won Best Rap Song, and even one of his pop crossover moments —his remix of Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood”—won Best Music Video, showing the breadth of his impact. Culturally, Butterfly sparked conversations well beyond music: it was analyzed in college courses and thinkpieces, praised by icons like Prince and Obama (who said his favorite song of 2015 was “How Much a Dollar Cost” from the album). With To Pimp a Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar had not only avoided the sophomore slump – he delivered a magnum opus that challenged and inspired, elevating him from star rapper to generational icon. The risk of blending free jazz skits about Lucy (a personification of temptation and Lucifer) with funk anthems about black unity paid off immensely. Kendrick had created a vivid soundtrack for black America’s pain and triumph, firmly securing his spot as an artist with a capital “A,” one who would be studied for years to come. — B.O.

untitled unmastered. (2016)

Surprise-released in March 2016, untitled unmastered. compiles eight tracks recorded during To Pimp a Butterfly sessions. Kendrick had teased these songs in high-profile spots like his unforgettable 2016 Grammys set and a captivating Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon appearance, where fans first heard glimpses of mysterious “untitled” cuts. The EP arrived with minimal fanfare but generated instant buzz. Though labeled unfinished, the tracks bristle with experimental jazz chords, twisted funk rhythms, and socially charged lyricism that echoes Butterfly’s spirit. From deeper meditations on race and spirituality to quirky ad-libs, untitled unmastered. offers a window into Kendrick’s creative process. Its success—landing #1 on the Billboard 200—proved that even his leftovers could galvanize the hip-hop scene, solidifying his reputation as an artist whose every scrap matters. — B.O.

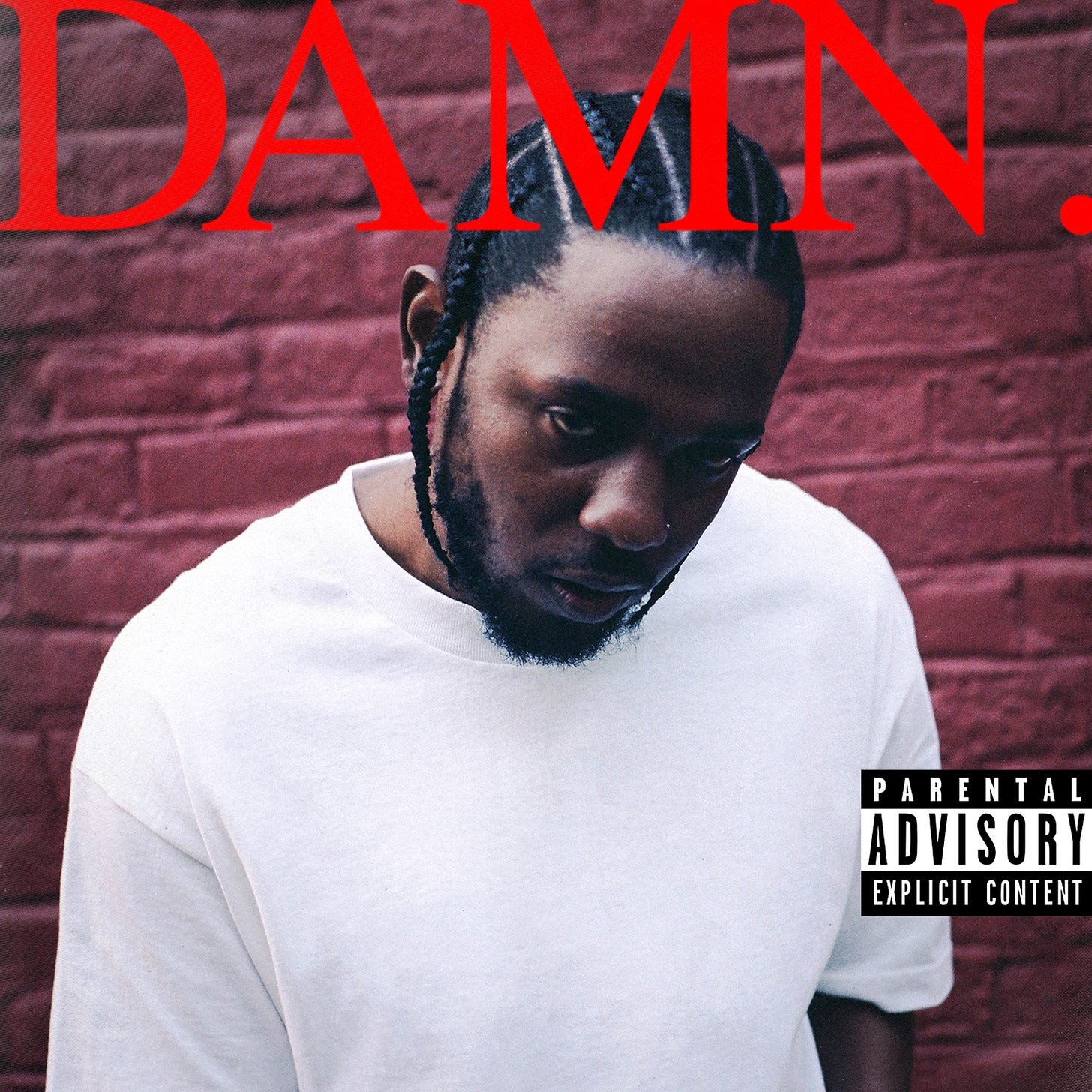

DAMN. (2017)

After the sprawling complexity of To Pimp a Butterfly, Kendrick’s next move was highly anticipated. He responded in 2017 with DAMN.—an album that distilled his artistry into a leaner, hard-hitting package without sacrificing depth. Sonically, DAMN. embraced contemporary rap’s polished production and booming 808s, resulting in some of Lamar’s most accessible music until his sixth album, which we’ll get there. The tracks often sported catchy hooks and head-nodding beats, from Mike WiLL Made-It’s rattling production on “HUMBLE.” to the moody groove of “LOVE.” featuring Zacari. This approach brought Kendrick heavy radio rotation and streaming success—“HUMBLE.” shot to #1 on the Hot 100 (his first solo single to do so) and became a ubiquitous anthem with its infectious piano riff and quotable boasts. On the surface, DAMN. offered bangers fit for clubs, cars, and festivals, proving Kendrick could dominate the commercial landscape alongside any of his peers.

Yet, as always with Lamar, multiple layers lay beneath the surface. DAMN. is threaded with themes of duality and fate, examining the line between weakness and wickedness, pride and humility, love and lust – each concept explicitly noted in its track titles (“PRIDE.”, “HUMBLE.”, “LOVE.”, “LUST.” etc.). Kendrick frames the album with a striking narrative device: in the intro track (“BLOOD.”) he tells a parable of himself being shot and killed, and in the outro (“DUCKWORTH.”) he reveals a real-life story in which, years ago, his father almost crossed paths fatally with the man who would later sign Kendrick (Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith)—a twist of fate that saved his life and career. This essentially means the entire album can be heard as a story that loops on itself; fans realized that if you play DAMN.’s tracklist in reverse order, a different narrative arc emerges, highlighting Lamar’s experimental album structure. Despite being more condensed and less overtly jazz-infused, DAMN. still brimmed with lyrical complexity and social commentary. On “DNA.” he celebrated and critiqued his identity over an adrenaline-pumping beat that switches into an absolute frenzy (with Kendrick spitting arguably one of his fiercest verses). On “XXX.,” featuring U2, he tackled American violence and hypocrisy, even incorporating a mid-song shift from a chaotic rap barrage to a somber rock-tinged plea. If To Pimp a Butterfly demanded intellectual unpacking, DAMN. hit with visceral force—immediate yet still thought-provoking.

At the 60th Annual Grammy Awards, Kendrick opened the show with a tour-de-force medley (joined by U2 and comedian Dave Chappelle) that addressed black experiences in America with unflinching imagery. He went on to sweep the rap categories that night, winning five Grammys, including Best Rap Album for DAMN. and Best Rap Song for “HUMBLE.” Then, in April 2018, DAMN. achieved an honor no album in hip-hop had before: it won the Pulitzer Prize for Music. The Pulitzer Board commended the album as “a virtuosic song collection unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African-American life.” This was a watershed moment not just for Kendrick but for hip-hop at large—an acknowledgment that his work transcended genre and stood on par with the highest forms of musical art. Kendrick’s reaction was humble (true to the album’s themes), but the world took note that a Compton kid’s rap album had entered the cultural canon in an unprecedented way. DAMN. solidified that Kendrick Lamar could achieve massive commercial success and uncompromising artistic vision simultaneously. By this point, he wasn’t just leading the pack in rap—he was pushing the boundaries of popular music, period. — P

Black Panther: The Album (2018)

In 2018, Lamar took on a new role as an executive producer and curator for Black Panther: The Album, the soundtrack to the blockbuster Marvel film Black Panther. Hand-picked by director Ryan Coogler, Kendrick oversaw the compilation of songs, crafting a sonic companion to the movie’s themes of African pride and responsibility. He opened and closed the album, and his imprint is felt throughout its tracklist—from the Grammy-nominated anthem “All the Stars” with SZA to the hard-hitting “King’s Dead” with Jay Rock, Future, and James Blake. Black Panther: The Album was both a commercial and critical hit, debuting at #1 on the Billboard 200 and introducing global audiences to the TDE sound. It earned multiple Grammy nominations and a win for “King’s Dead” (Best Rap Performance), and even nabbed Kendrick an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song (“All the Stars”). This project highlighted Lamar’s curatorial ear and ability to unite artists across genres under a cohesive vision. It also underscored his growing stature beyond the confines of his own albums—here he was shaping the musical identity of a major Hollywood film centered on Black heroes, further solidifying his cultural impact. — P

Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers (2022)

At long last, Kendrick returned with Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. It’s a double-disc album (disc one is “Big Steppers,” disc two is “Mr. Morale”), with 18 tracks split evenly, and it’s Kendrick’s most introspective and psychologically heavy project. If earlier albums examined his community, his generation, or his philosophical ruminations, this album turns the lens deeply inward— it’s essentially Kendrick’s journey through therapy, trauma, and growth, laid out over two halves. The overarching theme is about confronting personal demons: generational trauma, infidelity and relationship struggles, fatherhood, gender identity and transphobia, addiction, and the pressures of hero worship. It’s a very humanizing album—Kendrick, who many fans view as a near-infallible figure, exposes his flaws, contradictions, and pain in uncomfortable detail. One guiding concept is the idea of generational curses and healing. The term “Big Steppers” colloquially can mean those who are flexing or showing off, but in the album, it might represent people stepping through life and trying to ignore their issues with bravado. “Mr. Morale,” on the other hand, suggests someone taking moral inventory or leading the charge in truth-telling. The album doesn’t follow a linear narrative like GKMC, but it has a progression: the first half often portrays the problems and the coping mechanisms (stepping around issues), and the second half dives into confronting them (the therapy and morale part).

Important tracks and their themes include: “United in Grief,” which opens the album and immediately sets a confessional tone—Kendrick speaks about how he’s been going through something (the 1,855 days since his last release), and he outlines how he, like many, has coped with grief and stress in unhealthy ways (like material spending sprees). The refrain “I grieve different” indicates everyone has their way of processing pain, and he’s about to show us his. The album also marked Kendrick’s final project with TDE, as he moved fully to his pgLang company after (the album is co-released by pgLang). It felt like a closing of a chapter: he spent much of his 20s and early 30s being the voice of others, and Mr. Morale was about finding his own voice and addressing his own soul. Some fans missed the more outward-facing Kendrick, but many resonated with the maturity and bravery it took to release an album that, at times, feels like reading someone’s diary or sitting in on their therapy session. It may have mixed reviews, but over time, its reception may grow as listeners unpack it more and as stigma around some topics hopefully lessens.

“Mother I Sober” is the emotional climax of the album. This track, featuring Beth Gibbons of Portishead, is a haunting, almost bare confessional where Kendrick addresses the deepest roots of his trauma. He recounts how his mother was sexually abused, and once suspected young Kendrick might have been abused (by a particular family member)—he says, “I was never abused, I report it as a child, I hope I’m not too late,” basically he carries guilt for not being able to ease his mother’s fears and for the generational trauma of sexual abuse that runs in his family. He also reflects on witnessing his relatives and others falling into addiction and how that trauma spreads (“the damage by lies and betrayal, it was all I ever known”). This song is where he explicitly breaks the generational curse: “I set free our mothers, all the women, and masculinity.” The final line is his wife Whitney saying, “You did it, I’m proud of you. You broke a generational curse.” It’s a gut-wrenching culmination—he acknowledges the pain passed down through generations, and by speaking it aloud and seeking help, he’s trying to break the cycle so his children (he references his son and daughter) won’t inherit the same pain.

Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers is the sound of Kendrick Lamar at age 34, a father of two, a wife, a man who’s traveled the world and achieved the highest heights, coming back down to deal with the human stuff that even Pulitzer Prizes and fame can’t exempt you from. It’s not wrapped in a neat bow; it’s uncomfortable and challenging. But it’s an album that likely will be looked back on as ahead of its time in confronting issues of therapy, abuse, and emotional honesty in a genre that historically has often done the opposite (conceal pain behind swagger). Kodak Black’s presence as a sort of narrator/feature was controversial (given his own legal issues with sexual assault), but Kendrick likely included him to provoke thought about imperfection and to tie into the album’s themes of flawed individuals (Kodak also represents a younger generation who maybe is seeking guidance) and the one and only, Echart Tolle. Notably, it features tap dancing interludes—a recurring sound between tracks is someone tap dancing. This tap dance represents “stepping around” issues (as said by Whitney in an interlude: “stop tap dancing around the conversation”)—a clever sonic motif for avoidance. Kendrick essentially removed the last mask he had and refused to be put on a pedestal anymore, an act which in itself is quite revolutionary for a figure of his stature. — P

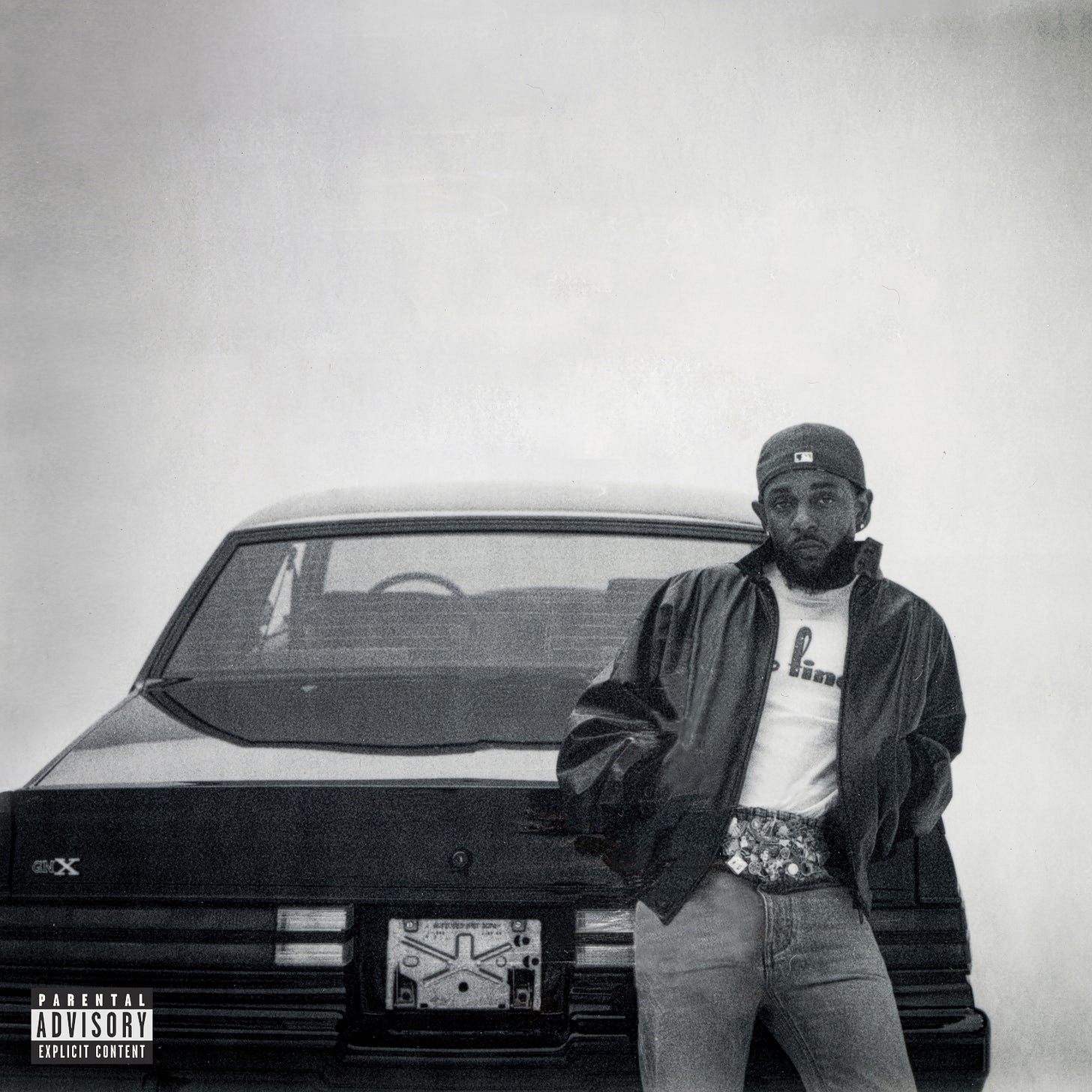

GNX (2024)

Titled after the 1987 Buick Grand National Experimental (GNX)—a rare, high-performance car—the album’s name carries symbolic weight. The Buick GNX holds personal significance for Kendrick: it’s mentioned that he bought one, and it was the same model that brought him home from the hospital as a newborn. Thus, GNX signals a return to roots and a journey back through his personal heritage, even as he moves forward. It’s also his first album after departing his lifelong label TDE and Aftermath, released under pgLang in partnership with Interscope. This context is key: GNX sees Kendrick fully at the helm of his artistry and business, driving solo, so to speak. Conceptually, GNX isn’t as overtly narrative-driven as some earlier albums, but it’s cohesive in celebrating West Coast hip-hop culture and Kendrick’s place in it while also reflecting on the tumultuous period that preceded it—notably his highly publicized feud with Lawbrey. The album feels like both a reunion and a reassertion. Reunion, because it heavily features L.A. artists and embraces local sounds and stories; reassertion, because it’s Kendrick staking his claim independently after proving himself in battles and breaking free of older contracts.

Leading up to GNX, Kendrick had dropped a string of diss tracks that topped the charts, like “Like That” and “Not Like Us,” which are the context for the album’s energy. GNX doesn’t explicitly dwell on the feud in lyrics (it’s more celebratory than bitter), but songs carry confidence and reference to overcoming challenges. For example, one of the singles, “Squabble Up” (unofficially teased earlier), uses fighting imagery playfully, possibly a nod to how he handled rap “squabbles” and came out on top. There’s also a theme of legacy and moving on: having left TDE/Aftermath amicably, GNX addresses carving a new lane while honoring the old. References to the GNX car tie into the idea of driving forward with the past in the rearview but not forgotten (the GNX being an ’87 car, the same year he was born, bridging his birth and now). Also, given the GNX car was known for being stealth-released by Buick in limited numbers (only 547 were made), the surprise drop of the album and its title show Kendrick aligning himself with something rare, powerful, and rooted in nostalgia.

Featuring local artists was a big element: guests include SZA (who’s from TDE but also an LA-adjacent R&B star), Roddy Ricch (Compton’s own melodic rapper), and a bunch of emerging L.A. rappers like Wallie the Sensei, AzChike, and others from the L.A. scene. This roster makes GNX feel like a block party or a cruise through L.A. with Kendrick bringing the city with him. SZA’s feature might be a smooth R&B cut or a hook on a radio-friendly song—their collaborations (“All the Stars,” “Babylon,” “Doves In the Wind”) are always notable. Roddy Ricch might bring the melodic street vibe. Lesser-known names show Kendrick giving shine to new blood (similar to how he put his cousin Baby Keem on earlier projects), reaffirming his position as a leader who uplifts his region. GNX was primarily handled by Sounwave (Kendrick’s longtime producer) and notably Jack Antonoff, a prominent pop producer (known for Taylor Swift, Lorde, etc.), which is intriguing. This combination yields a sound that is at once classic West Coast and somewhat glossy or experimental.

His sixth studio effort is a ride through Kendrick Lamar’s West Coast world, reflective of cruising down Compton Boulevard in a classic car with the system bumping. It merges the personal (the car symbol, the independence) with the communal (all the featured friends and references) and shows Kendrick in celebration mode after years of intense introspection and conflict. As for legacy, GNX, in just the short time since release, seems to have reinforced Kendrick’s consistency—six albums in, and he’s still delivering quality while evolving. It also adds to the narrative of his career that he can go head-to-head in beef and still keep his artistic integrity (few rappers come off a diss-track spree and drop an album that stands on its own artistically). If previous albums were heavy with burdens, GNX is freer. It does not lack depth, but it has a sense of victory and release. — B.O.