Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen: From Spirituals to Secular Song

Blackness between emotion and prejudice.

SPIRITUALS

Spirituals are the first form of solace that Black Americans embraced once they were introduced to the church of their white masters.

In addition to meeting religious needs, spirituals quickly became secret tools of communication, mapping out escape routes to freedom. Thanks to several white abolitionists in the North—outraged by how Southern landowners treated their slaves—the Underground Railroad was born: a covert network through which Black people escaping bondage could reach free states and Canada. Behind the indisputable religious message, many spirituals carried a secondary meaning, one that pointed the way along this “underground railroad.”

These escapes, however, were anything but simple. When slaveholders caught on, they called on sheriffs and bounty hunters to bring the fugitives back. At that point, those who were caught would be massacred—to make an example of them and deter anyone else with similar ideas.

When the Civil War ended, Black Americans got a brief respite, and a small Black middle class began to form. But in the subsequent Reconstruction era, they again became targets of reprisals and suffered even worse abuse, because with no “master” officially in charge, anyone could take out their anger freely. It was then that the long plague of lynchings began.

A NEW RELIGION: THE SPIRITUAL

The long period of slavery that followed the diaspora was also a grueling struggle to remain connected to original African culture. The masters’ religion was the most immediate lifeline to relieve the physical and existential anguish of daily life, yet it also became a way of identifying with the people of Israel, with all their hardships and ultimate deliverance. In fact, the biblical stories gave enslaved people a chance to see themselves in the story of Israel, which had also suffered greatly before reaching the Promised Land. Even if for many the Promised Land was just a metaphor—be it Africa or Paradise—these biblical narratives provided one of the only consolations that allowed them to face yet another day of hardship and labor.

“I have lived the slavery of the Deep South on my own skin, so what I cannot stand is seeing it represented by whites on a stage or in a theater.” — Harriet Tubman

In this new religion, then, Black people found the strength to express their own ideals and hopes for freedom. Over time, not only did they attend church services, they also began taking part actively—singing in the choirs, creating a truly new kind of song that communicated directly with God: the spiritual. The great themes woven into spirituals often centered on biblical characters and events. Moses, for instance, made a strong impression on Black Americans, who recognized in him the hero and prophet—divinely chosen to free his people from Pharaoh’s slavery. An inevitable process of identification took place, which secretly nurtured the hope of a return to Africa. “Go Down Moses,” perhaps one of the most famous spirituals, emerged from this very idea:

When Israel was in Egypt land…

Let my People Go!

Oppressed so hard they could not stand…

Let my People Go!

Go down in Egypt’s land,

Tell old Pharaoh,

Let my People Go!

“Thus saith the Lord,” bold Moses said,

Let my People Go!

The longing for Mother Africa was great, and it could also be evoked by speaking of a child deprived of his mother’s love—as we hear in “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.”

ODETTA

Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child

Traditional

This is an old spiritual dating back to slavery. It was first performed professionally by the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the latter half of the 1800s and then revived in the first “revival” of the 1920s by Paul Robeson. Later, in the ’50s and ’60s, Odetta offered the most famous rendition. The spiritual is a raw lament about the pain of someone who feels like a child torn from its mother’s arms—a metaphor for the anguish of the diaspora from “Mother Africa” imposed by the slave trade.

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child /

Far, far away from home /

A long, long way from home.

Then I get down on my knees an’ pray,

Get down on my knees an’ pray.

Spirituals and “jubilees,” which differ somewhat from earlier forms in that they celebrate hope for a brighter future, follow a call-and-response format between the preacher and the congregation. Over time, the preacher’s role and that of the faithful gave rise to the soloist and choir. Both traditions spring directly from work songs in a religious guise—songs that already included call and response. Officially, they came into being when Black people, fully indoctrinated, could create autonomous churches, especially Baptist and Methodist. They aren’t just straightforward religious compositions; over time, incorporated into the Mass, they became the heartfelt wail of a suffering people. For enslaved Black congregations, Jesus came to embody the suffering soul of an entire race. The despair running through Black spirituals is an appeal to God, a prayer to be welcomed into His Kingdom—the only place that can bring solace to earthly sorrows.

THE BAPTIST, METHODIST, AND ADVENTIST CHURCHES

Christianity was forced on enslaved people in various ways, depending on the denominations their masters observed. Indeed, different religious movements had sprung up since the sixteenth century in Europe following the Protestant Reformation and began organizing themselves as independent churches. Baptists originated in England during the seventeenth century as a very simple structure, focusing on personal responsibility, and advocated adult baptism as a way for believers to bear witness to their faith. The Baptist Church, maintaining the right to freedom of conscience and religion, spread rapidly in the United States—particularly among Western pioneers and enslaved African Americans on Southern plantations. Beyond the emotional elements of faith, the fact that Baptist preachers allowed enslaved people to conduct their own services and even become preachers or deacons, able to officiate within the plantations, helped make faith a cornerstone of their lives.

Methodism also arose in England about a century later under the Anglican minister John Wesley, who promoted a systematic (or “methodical”) approach to Bible study, requiring weekly gatherings for in-depth, personal discussion aimed at radical inner transformation. Their name—Methodists—comes directly from this “methodical” structure, by which the faithful are required to fulfill these obligations.

The Adventist Church emerged more recently, in the nineteenth century in the United States within a Baptist context. It is characterized by a strong anticipation of Jesus Christ’s imminent return (hence the name). Among these denominations is the Seventh-day Adventist Church, known for strictly observing Saturday as the Lord’s Day.

In “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” the chariot represents the vehicle that carries souls of the departed to Heaven, where they can finally find peace with their loved ones who have gone before.

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home.

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home.

Certain elements of Christian worship proved especially appealing to Black people because they closely resembled older African rituals. Baptism, for instance, as practiced by Baptists and Methodists, involves total immersion in water—somewhat recalling ancient oral traditions that view the river itself as a purifying deity. In their film O Brother, Where Art Thou? (Italian: Fratello, dove sei?), the Coen Brothers beautifully depict these mass baptisms, hovering between ecstasy and gentle irony.

On this note, it’s impossible not to mention “Down By the Riverside,” where, once again, the hardships of earthly life are endured in the hope of a better life in Heaven.

Oh, hallelujah to the Lamb,

down by the riverside;

the Lord is on the giving hand,

down by the riverside.

(Chorus)

Oh, we’ll wait ‘till Jesus comes,

down by the riverside,

we’ll wait ‘till Jesus comes,

down by the riverside.

THE LANGUAGE OF THE SPIRITUAL

AN INTIMATE FORMULATION

Often, anthologies that feature the lyrics of spirituals opt to present them in substantially “proper” English—understandably, to make them easier to read. Yet the enslaved people on the plantations—who were strictly forbidden from learning to read or write and had no written references—had to pick up their masters’ language by ear, overhearing orders and conversations, then reproducing them as closely as possible to the sounds they heard. Thus arose a kind of distinctive slang, marked by contractions and grammar that can puzzle modern readers. This way of speaking very much reflects both the mindset and the expressive style of those who created these songs. The opening lines of the spiritual “Dese Bones Gwine Rise Again” provide a glimpse of how it might originally have been formed:

De Lawd, he thought he’d make a man Dese bones gwine rise again Made ‘im outa mud an’ a han’ful o’ san’ Dese bones gwine rise again

This slang added extra potency to the singing, infusing it with an intimate, poetic dimension of great evocative power.

Oh, chillun, oh, don’t you want to go, to that gospel feast, that promised land, that land, where all is peace? Walk into heaven, and take my seat, And cast my crown at Jesus feet Lord, I want to cross over into camp-ground (3).

The imagery of crossing a river is frequently used as a metaphor for the road to freedom. With that in mind, “Wade in the Water” is considered one of the most meaningful spirituals:

Wade in the water. Wade in the water children. Wade in the water. God’s gonna trouble the water. See that band all dressed in white, God’s gonna trouble the Water, It looks like the band of Israeli, God’s gonna trouble the Water.

Certainly, these lyrics can be read in a purely biblical sense. Yet many people believe the lines hold hidden instructions for enslaved people planning their escape, advising them on the best route to freedom. Specifically, these verses may be encouraging runaways to leave the safety of dry land and wade into the water—since the current could confuse any bloodhounds sent to track them. The journey through a flowing river is risky, so “God’s gonna trouble the water” is also a warning to remain cautious and alert throughout the crossing. You have to move slowly, because one wrong step could send you tumbling into capture.

As the next section will show, songs like these were later used by abolitionist supporters to pass on coded guidance to freedom seekers.

SISTER ROSETTA THARPE

Down by the Riverside

Traditional

This spiritual traces back to the American Civil War era, although it was not published until 1918 in the anthology Plantation Melodies: A Collection of Modern, Popular and Old-Time Negro Songs of the Southland. Its first recording came courtesy of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who released it in 1920. Apart from the standard biblical references, a markedly practical layer of meaning is evident here, too—namely, offering instructions to people escaping enslavement on their way north toward freedom.

NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I’VE SEEN

WHEN SUFFERING BECOMES SONG

“Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” is an old African American spiritual dating from the time of slavery, although it wasn’t published in written form until 1867. By faithfully capturing what must have been the mindset of the enslaved—exhausted by forced labor and devoid of hope for redemption—this piece swiftly became a classic. It has been covered countless times. With only a few verses repeated in classic spiritual style, the anonymous composer managed to convey an intensely personal emotional state that transcends its tragic origins to become universal. Many of the more recent covers are those by Paul Robeson and Sam Cooke. However, as early as 1925, Marian Anderson recorded a successful version for the Victor label; Lena Horne picked it up in 1946, and Louis Armstrong recorded it in 1962. In 1958 the Deep River Boys took it into the charts with an arrangement by Harry Douglas:

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen Nobody knows but Jesus Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen Glory HallelujahSometimes I’m up Sometimes I’m down, Oh, yes Lord; Sometimes I’m almos’ to de groun’ Oh, yes Lord.

THE HIGHWAY TO FREEDOM

The Underground Railroad was a secret network that carried people from slavery to freedom. Certain white abolitionists first set it up, and later, Black “freedpeople” used spirituals as a coded language to mark the route to the North.

Massachusetts officially recognized slavery in 1662. Seeing the profits that could be had, other American colonies gradually fell in line with Boston’s rulings. By 1776, with independence declared from England, slavery in the United States had become entrenched as an accepted institution. Control over an enslaved person was inseparable from the plantation owner, who held the power of life and death. The slave existed solely for his master and was viewed as private property, which third parties could not abuse unless the master authorized it. Rules dictated plantation life, and a slave’s wellbeing depended on the moral character of the master who had purchased him. If the slave was a man who disobeyed, he faced harsh punishments and backbreaking labor. If a woman—perhaps young and appealing—she could be forced to satisfy the master or anyone else who had authority over her.

Somewhat paradoxically, conditions for Black Americans after the Civil War grew worse in certain respects. Slavery was abolished, yet during the ensuing Reconstruction period, little was done to restrain the power of Southern states or ensure genuine social and economic recovery. Enslaved people, though nominally “freed,” were often left entirely on their own and were easy targets for vengeance, having no one to defend them from abuse.

Still, enslaved people repeatedly tried to flee. Quakers—religious communities convinced of slavery’s immorality—stepped in to support them. Toward the late 1700s, a more structured system evolved, creating real escape plans with shelters, guides, and various means of transportation. Plantation owners, alarmed at the potential loss of their enslaved workforce, pressed Congress to enact a law mandating the capture and return of runaways, even if they had already reached a free state. As a result, the Fugitive Slave Act was adopted in early 1793, making an enslaved person’s journey to freedom far more dangerous. The law included provisions for penalizing anyone who helped or sheltered a runaway, including a fine of five hundred dollars. Legally, any slave on the run was branded a “fugitive for life” and could be caught at any time, anywhere in the United States. Even those who gave birth while enslaved conferred slave status on their children, perpetuating the cycle.

“If a slave escapes, the county sheriff who fails to find him may be sued for the full value of the labor lost by the runaway himself.” — Fugitive Slave Act (Section 4)

This law also ushered in an odious new market of bounty hunters—unscrupulous men who took it upon themselves to track down fugitives, capture them, and return them to the plantation to face punishment. Sometimes they would abduct free Black people and sell them into slavery, fraudulently claiming they were escaped slaves. Because people of color had virtually no legal recourse, they could not prove their freedom in court. Their guilt was presumed.

Northern abolitionists responded with outrage. They fought back by passing “personal liberty laws,” aimed at obstructing Southern authorities who tried to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. Indiana did so in 1824; Connecticut followed in 1828, granting those arrested as fugitives the right to appeal—rights the law had previously denied them. By 1840, states such as New York and Vermont upheld an accused fugitive’s right to a jury trial and provided legal assistance. Opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act carried on into the early 1900s, operating as a systematic anti-slavery movement that helped people escape south to Florida, north to Canada, or even overseas to England. This network became known as the Underground Railroad.

The Railroad was especially active in the first half of the 1800s, and it’s thought to have facilitated tens of thousands of escapes. Major routes out of the South crossed Ohio, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York. People traveled by night, guided by the North Star, hiding by day in safe houses until they arrived at locations where they could disappear, or continue on to Canada.

“If a slave escapes, the county sheriff who fails to find him may be sued for the full value of the labor lost by the runaway himself.”

(Repeated from above, referencing Section 4 of the Fugitive Slave Act.)

As part of this secret exodus, a sophisticated communication system developed—sometimes referred to as the “grapevine telegraph”—alerting those who awaited and assisted runaways at each “station.” Teaching enslaved people to read and write was illegal in most Southern states, so coded messages were often conveyed through songs, indicating where, how, and when to flee. Many of those songs were spirituals.

These “musical signals” served to warn of dangers and obstacles ahead. If someone approached while one of these songs was being sung—for example, “O Canaan, sweet Canaan / I am bound for the land of Canaan,” cited by Frederick Douglass—it would be perfectly clear which guide to follow.

O Canaan, sweet Canaan / I am bound for the land of Canaan

No need to say anything more: an enslaved person could readily interpret the message. “Canaan” was a metaphor for the North—and for the promise of liberty.

Among the best-known guides to freedom was a formerly enslaved woman, Harriet Tubman, nicknamed the “Black Moses.” To make her presence known, she even wrote a song herself: “Dark and Thorny Is the Patta,” a slight variation on the traditional “Dark and Thorny Is the Desert,” an unmistakable allegory for the dangers one might face on the paths to freedom:

Dark and thorny is the pathway Where the pilgrim makes his ways; But beyond this vale of sorrow Lie the fields of endless days

HARRIET TUBMAN

THE “BLACK AMERICAN MOSES”

If you walk through the streets of Harlem in New York, you’ll come across roads with legendary names that recall the great architects of the struggle to abolish slavery and secure civil rights. Right at the intersection of St. Nicholas Avenue, 128th Street, and Frederick Douglass Boulevard stands a large bronze sculpture depicting Harriet Tubman, leader of the Underground Railroad and the first woman to lead an armed assault during the American Civil War.

Born into slavery in Maryland in 1822, Harriet Tubman—whose given name was Araminta Ross—escaped north at the age of twenty-seven, bringing with her the two brothers who were about to be sold. They succeeded by way of the Underground Railroad, a network of people and routes that stayed active until the Civil War, providing aid and shelter to enslaved individuals seeking freedom. From that time on, she dedicated her life to helping Black people flee captivity. On her own, she saved seventy people, personally guiding them along the routes of the “Underground” Railroad (so called because it could make enslaved people vanish as if swallowed by the earth, only to reappear once they reached abolitionist territories).

Because of her unrelenting efforts, plantation owners placed a heavy bounty on her head—at one point offering forty thousand dollars for her capture or death. Still, she always stayed one step ahead of the bounty hunters and managed to bring every “passenger” in her care to safety.

Drawing on the skills she developed during her Underground Railroad missions, Harriet served as a scout for the Union Army in the Civil War and also distinguished herself as a tireless nurse in the field. Owing to the beatings she suffered in her youth, she spent her entire life plagued by severe headaches and seizures. She died of pneumonia in 1913.

Fiends, loud howling through the pathway, Make them tremble as they go; And the fiery darts of Satan Often bring their courage low.

It was Harriet Tubman herself—who by night led her brothers in the grueling treks toward free states in the North via secret Underground Railroad routes—who loved to sing “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” One of her favorite songs, it doubled as a kind of password, guiding those escaping from Alabama toward the Ohio River and, ultimately, freedom.

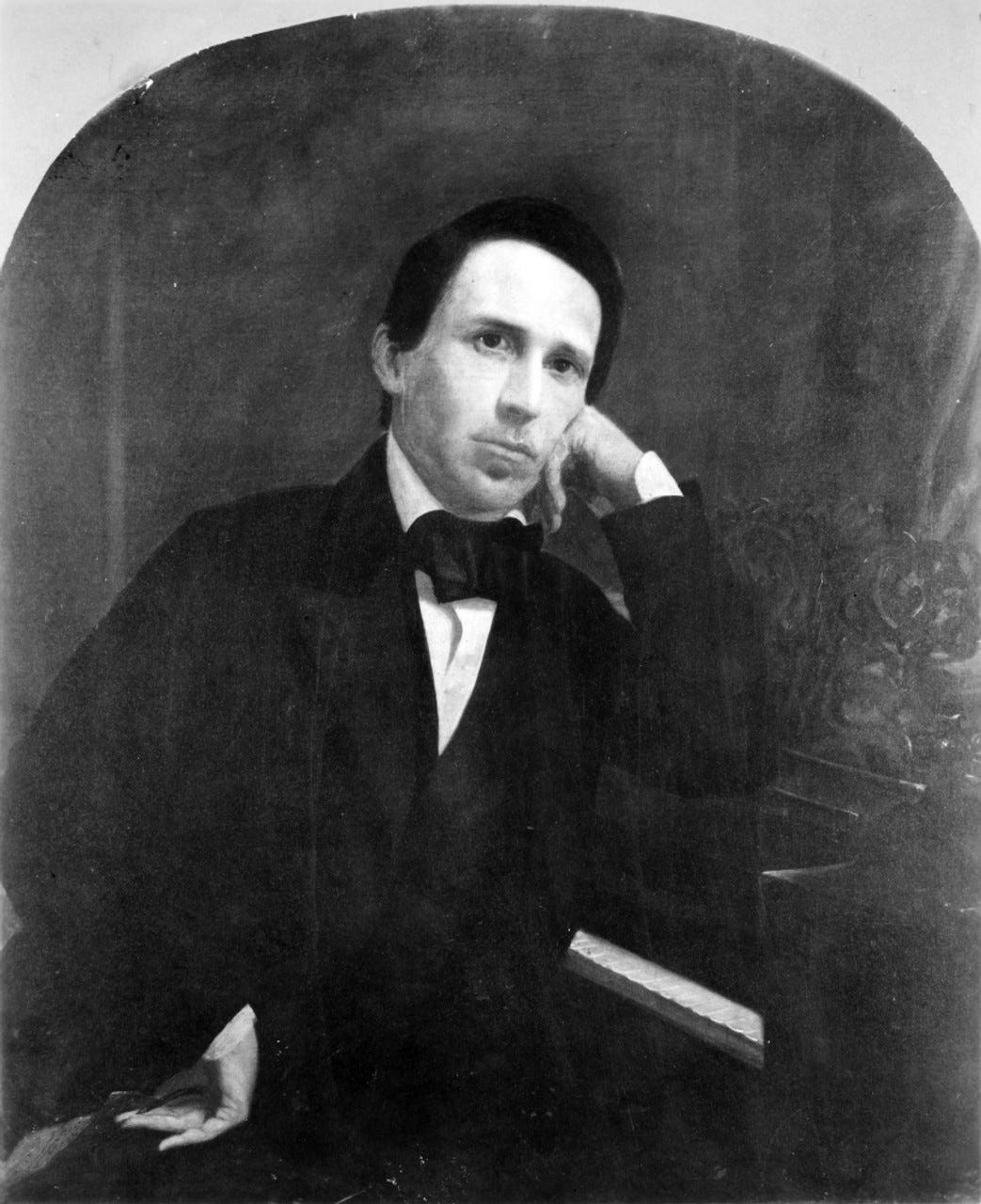

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

AN AMERICAN SLAVE

Frederick Douglass was an escaped slave who became both a prominent politician and an abolitionist writer. In 1845 he published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, describing the trials he had to overcome to become a free man. His determination led him, in 1872, to become the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States (on the Equal Rights Party ticket) alongside Victoria Woodhull, herself the first woman to run for president.

In his autobiography, Douglass recounts the horrific events that shaped his early life—experiences shared by many enslaved people. For instance, most never knew their birthdate, let alone their parentage. Douglass mentions having only a faint memory of his mother, from whom he was quickly separated, and never knowing his father; he suspected it might have been a white man—possibly the plantation owner himself. As a child in slavery, young Frederick witnessed brutal episodes, such as the lashing of his Aunt Hester, which left a profound mark on him.

When Douglass was a teenager, he was “rented out” to a family in Baltimore. The mistress, Mrs. Auld, initially taught him the alphabet and how to read, though her husband disapproved, believing that education would turn him into a dangerous slave. Douglass grasped the importance of literacy and continued to pursue it secretly, learning by watching the white children around him do their homework. After the master’s death, Douglass was passed from one owner to another, eventually ending up with a certain Mr. Covey, known for his cruelty. Field labor and constant beatings led to multiple showdowns, culminating in a physical confrontation in which Douglass overcame Covey. Taken aback by the young man’s strength, Covey backed off, not wanting to harm his reputation by selling Douglass.

Later, on another plantation, Douglass bonded with enslaved people who could read and write. Together they planned an escape that failed. He was jailed and then sent back to Baltimore to learn a trade at a shipyard, though his skin color made his work there risky, and he came close to losing an eye. Desperate, Douglass realized that escaping was his only option. He fled to New York, then to New Bedford, finally attaining freedom.

Enslaved Black people called the Big Dipper “The Drinking Gourd,” likening it to a hollow gourd used for holding water on long journeys. The last two stars in its handle point to the North Star, leading them out of the Southern states and toward liberty.

When the sun come back, When the firs’ quail call, Then the time is come Foller the drinkin’ gou’d.

“I prayed for twenty years and never got an answer until I prayed with my legs.” — Frederick Douglass

The riva’s bank am a very good road, The dead trees show the way, Lef’ foot, peg foot goin’ on, Foller the drinkin’ gou’d.

Follow the Drinking Gourd

Traditional

“Drinking Gourd” is the popular term by which Black people referred to the Big Dipper constellation. Its final two stars point to Polaris, thus indicating north, a crucial destination for those fleeing enslavement. This spiritual, born in the era of slavery, served as part of the Underground Railroad’s coded instructions, guiding people from Alabama and Mississippi to the Ohio River. According to tradition, one key figure in spreading these directions was Peg Leg Joe, an itinerant carpenter who spent winters traveling through the South, going from one plantation to another, teaching enslaved people this escape route.

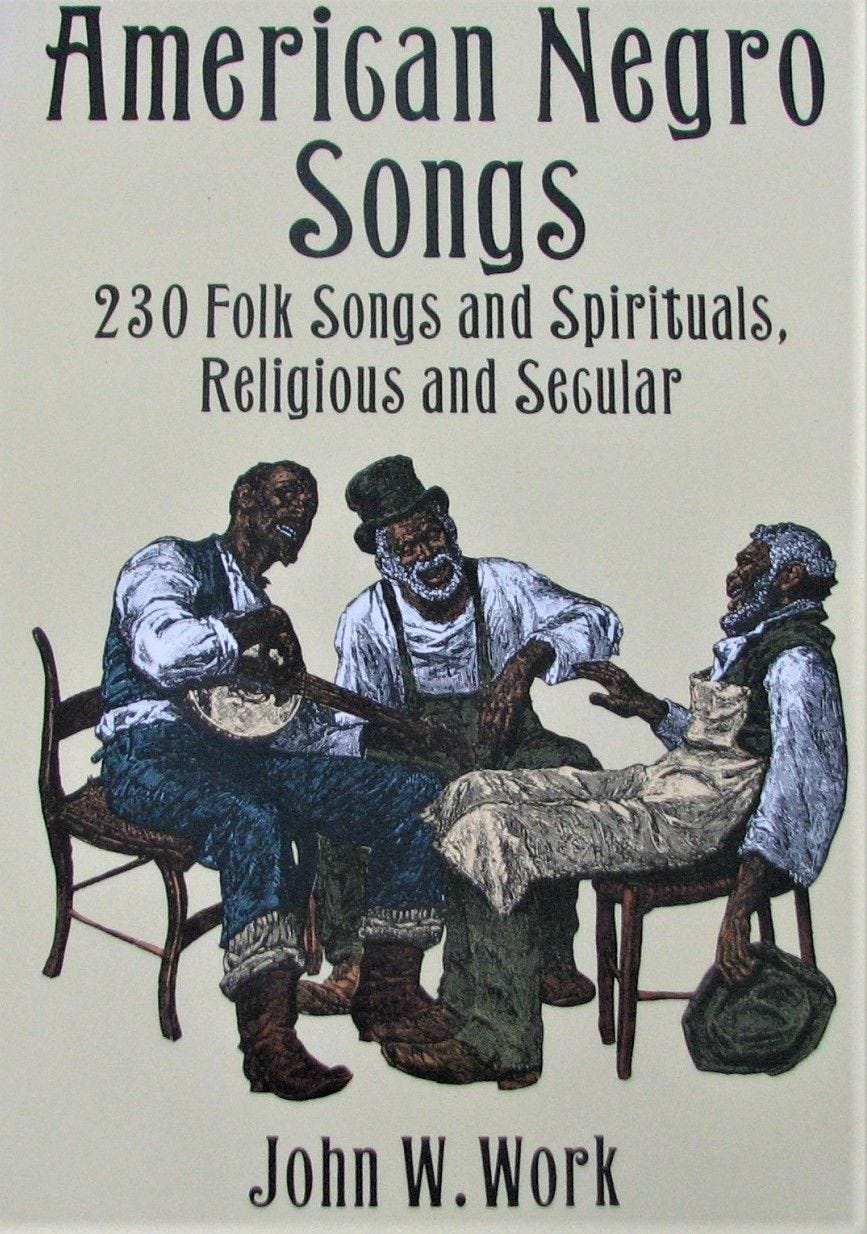

FISK JUBILEE SINGERS

THE FIRST PROFESSIONAL SPIRITUAL ENSEMBLE

John Wesley Work Jr. (1871–1925)—known as John Work II—spent thirty years at Nashville’s Fisk University (a historically Black college), working to collect and disseminate the “jubilee singing” of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers, an African American student choir performing a cappella. He achieved fame by opening spirituals up to a broader audience. In 1901 he and his brother Frederick J. Work published New Jubilee Songs as Sung by Fisk Jubilee Singers, a major anthology of spirituals that includes the now-classic “Wade in the Water.”

A signature technique of this group was the so-called “closing chord,” perfectly showcasing their vocal blend. The lead-singer’s call would merge with the choir’s response, creating overlapping voices and a spine-tingling falsetto. Ella Sheppard, one of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers—and also a composer and musical arranger—explained that initially, these “slave songs” were seen as too overtly religious for a concert repertoire. Yet Frederick Douglass had described them as “true prayers,” whose powerful, resonant tones expressed the anguish and sorrow of those in bondage, calling them “both a testimony against slavery and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.”

In his seminal 1903 work The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois dedicated an entire chapter to what he termed the “Sorrow Songs,” referring to them as “the musical gift of the American Negro … the singular expression of this nation’s faith.”

The original Fisk Jubilee Singers soon began touring to raise funds for the university, promoting spirituals. Their debut performance took place on October 6, 1871—Jubilee Day.

They found early public success: in 1872, they sang at the White House and performed at that year’s World Peace Festival in Boston, drawing enough acclaim to prompt European tours. By 1878 the original choir disbanded, but they passed the baton to Ella Sheppard Moore, who returned to Fisk determined to train a new generation of “jubilee” singers, which included her own son, John Work III. In 1899, Fisk’s president E.M. Cravath tried to assemble a mixed-voice ensemble to keep touring, but the costs proved too high. Ultimately, the project settled on a men’s quartet organized by John Work II. The group earned widespread praise and recorded for premier labels such as Victor, Columbia, and Starr.

When Work II died in 1925, Paramount released the ensemble’s first commercial recording of “Wade in the Water” under the name Sunset Four Jubilee.

The current of the river, besides pointing out the path—just as we’ve noted—helps mask the fugitive’s scent from the bloodhounds on their trail. Stars and flowing water frequently appear in spirituals connected with the Underground Railroad.

Other spirituals like “Steal Away,” “Children We All Shall Be Free,” and “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?” resound for those in bondage as a clarion call to escape toward freedom, while songs like “We’ll Stand the Storm” and “We Shall Walk Through the Valley in Peace” provide a calming reassurance for troubled souls.

“When they offer you emptiness with a smile and, in the meantime, rob you of your self-love, you have to remember who you are.” — Colson Whitehead

Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus. Steal away, steal away to home, I ain’t got long to stay here. My Lord calls me, He calls me by the thunder. The trumpet sounds within my soul, I ain’t got long to stay here.

Behind the overtly religious invitation to approach Jesus lies another summons: that of the Underground Railroad, guiding people toward freedom.

Songs of recognition were undoubtedly numerous, and it is quite probable that some were devised with certain tricks so they could warn of sudden changes that might occur if there were setbacks. Additional metaphorical verses may have been added to communicate changes in “stations” for meeting up, altered departure times, and who knows what else.

Unfortunately, aware of the risk that a plan for escape could be discovered, any documentation relating to the Underground Railroad was systematically destroyed as soon as it was used. Consequently, much of the information we have on this topic is often derived only from oral traditions or from literary works from that era, such as the famous Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, a staunch abolitionist, or more recent novels like The Underground Railroad (2016) by Colson Whitehead, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Naturally, not every escape attempt succeeded, and even for those who didn’t make it, songs were composed that lent consolatory momentum to their journey.

Wade In the Water

Traditional

This African American spiritual, which originated during the slavery era, can easily be linked to the Old Testament story of Moses fleeing Pharaoh by crossing the Red Sea. Yet it also functioned as a code and source of inspiration for Black people seeking freedom. The song encourages escapees to use river water to make their way north, avoiding discovery by the bloodhounds unleashed against them by sheriffs from various Southern counties.

“RECONSTRUCTION” AND MINSTREL SHOWS

After the apparent liberation from slavery brought on by the Civil War and the emergence of a small elite of free Black Americans, came the period of Reconstruction, during which the old Southern traditions were reestablished. Now that Black people were no longer subject to owners, they could be persecuted by anyone at all who wished to do so.

At the end of the Civil War (1861–1865), the Confederate States of the South suffered extremely heavy losses, drastically reducing the male population and undermining the availability of vital laborers needed to rebuild many devastated cities. What followed was a disastrous economic collapse caused by the crash of banks and railroads.

Per capita income in the defeated states fell to less than 40% of that in the North—a dire circumstance that lasted well into the second half of the following century. It was inevitable that the old political influence over the federal government would be diminished, particularly in the Republican Party, which still included a hardline faction determined to impose legislative measures unfavorable to the South.

Opposing the Republicans in the federal government were the Democrats, led by Andrew Johnson, the governor of Tennessee. He became president when the Republican Lincoln was assassinated. While Lincoln had been prepared to grant full civil rights to all freed slaves (freedman), Johnson instead acted opportunistically to appeal to white southerners’ fears. Though emancipation had occurred, Johnson avoided continuing on Lincoln’s path, creating ambiguity that would explode in widespread violence against Black people in nearly all the former Confederate states. In May 1866, Memphis witnessed numerous murders, assaults, and thefts targeting freedpeople. Then in New Orleans, that July, came yet another massacre against a peaceful crowd of African Americans. Over 38 were killed and 150 were injured.

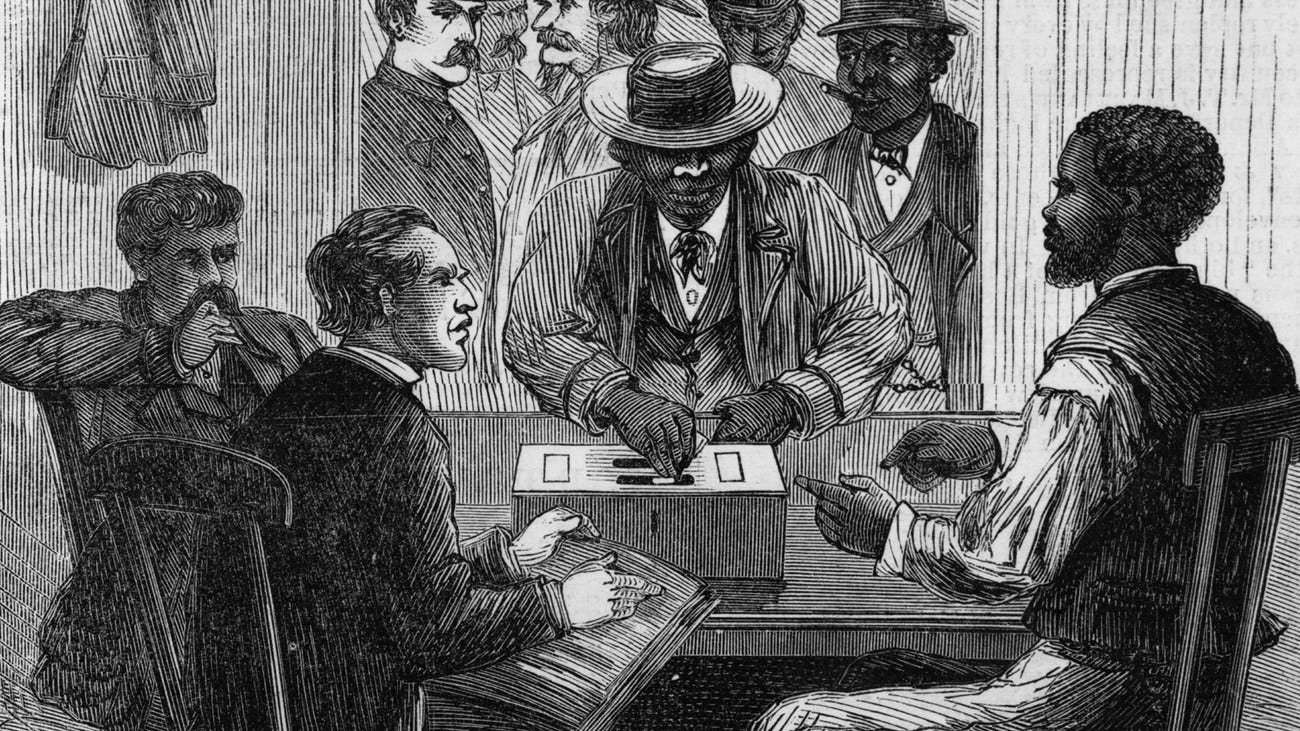

Such events fueled anger and sparked the Republican push to pass the 14th Amendment in 1867, granting formerly enslaved people the right to vote and equal civil status. Holding a majority in Congress, the Republicans used the federal army to maintain public order in the South and protect freedpeople. At the same time, many northerners—committed to educating formerly enslaved people—migrated south, becoming the so-called carpetbaggers, much reviled by southerners.

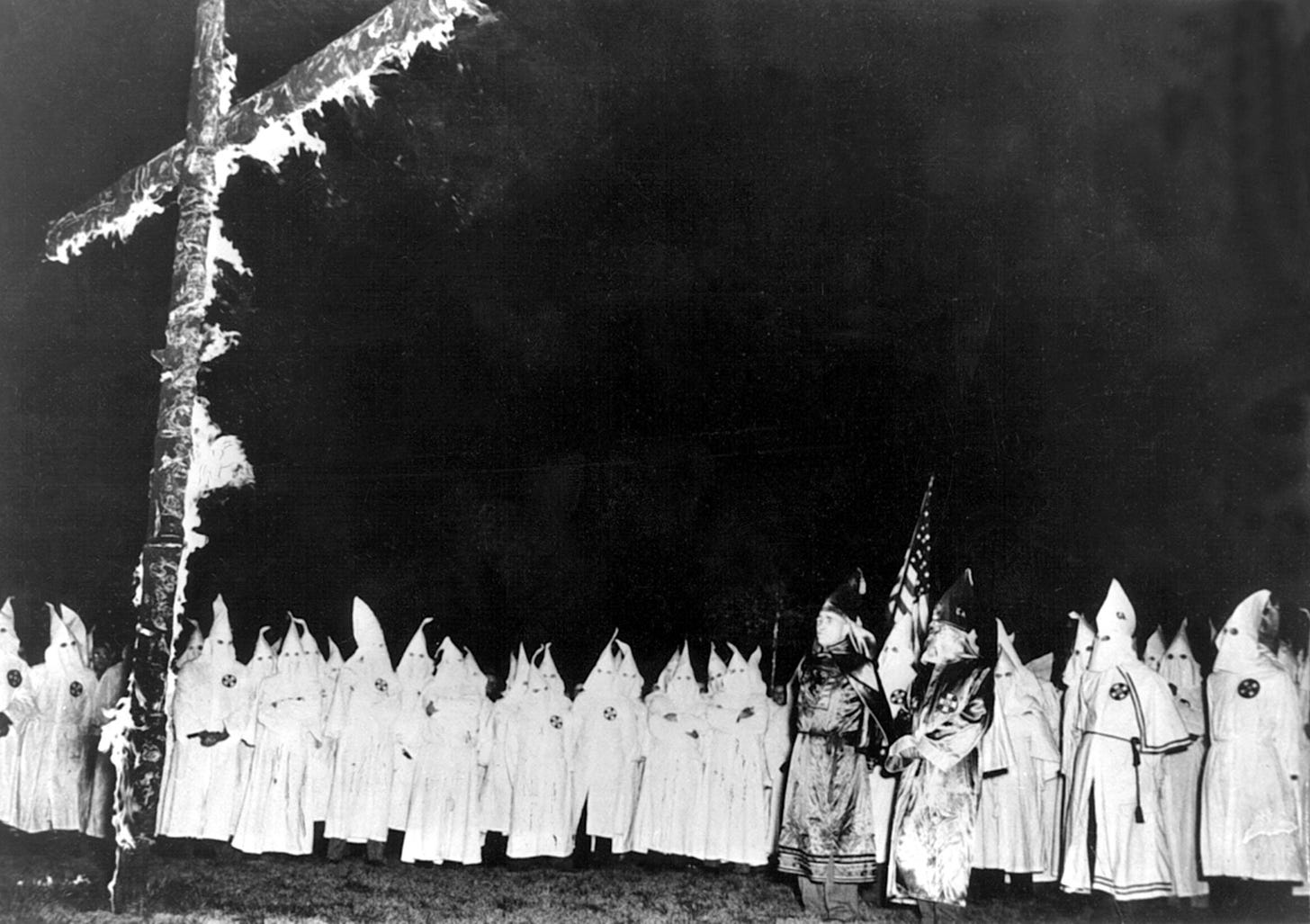

In this precarious situation, Southern pride was put under tremendous strain and soon gave rise to secret racist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, founded at the moment the 14th Amendment was passed. The Klan murdered Black people at random, set their homes ablaze, and assassinated white Republican allies. In 1867 and 1869 hundreds of these murders were recorded, including the killing of James M. Hinds, a progressive congressman from Arkansas.

“Although He is regularly asked, God never takes sides in American politics.” — George J. Mitchell

Once Ulysses S. Grant—an ex-Union general from the Civil War—was elected president, the more radical Republicans managed to pass new reforms. Indeed, protection for the freedmen came under the Enforcement Acts, which introduced measures to aid them economically and empowered them to combat the Ku Klux Klan. Within a short time, the Klan was dismantled, only to rise again in the 1920s.

But beyond the radical faction that continued its reformist agenda, many Republicans soon broke with them. In particular, many Southern lawmakers, the so-called scalawags, worried about the excessive taxes earmarked for rebuilding the South, began drifting toward the more extreme faction of the Democratic Party. Allies joined them—redeemerconservatives eager to reverse the course. By 1874, thanks to intimidation and various forms of voter suppression, Democrats were back in control in numerous states, and with the tacit National Compromise of 1877 (in which Rutherford Hayes took office as President in exchange for pulling federal troops out of the South), it effectively ended federal oversight of the new local governments. Immediately, many of these localities introduced restrictions that effectively removed African American voters from the lists.

With Jim Crow laws, the segregation of Black people from the white population became entrenched throughout the South.

In this political and cultural climate, a popular form of entertainment took shape: the minstrel show, which reached its peak in the 1860s but had already existed for around three decades. It was a blend of music, dance, and variety theater in which white actors, with their faces painted black (using burnt cork or “blackface”), portrayed Black people according to stereotypical behavior, painting them as lazy buffoons and incorrigible clowns. The main musical instruments used by these performers were the banjo and fiddle, a comedic caricature of the music once performed by enslaved people. Though said to be “traditional,” it was actually a mythicized, distorted version of genuine African American culture. In reality, minstrelsy was not an invention unique to white Americans; it was a reinterpretation of music and dances that had evolved during slavery, an era when plantation owners themselves might enjoy an enslaved person’s performance.

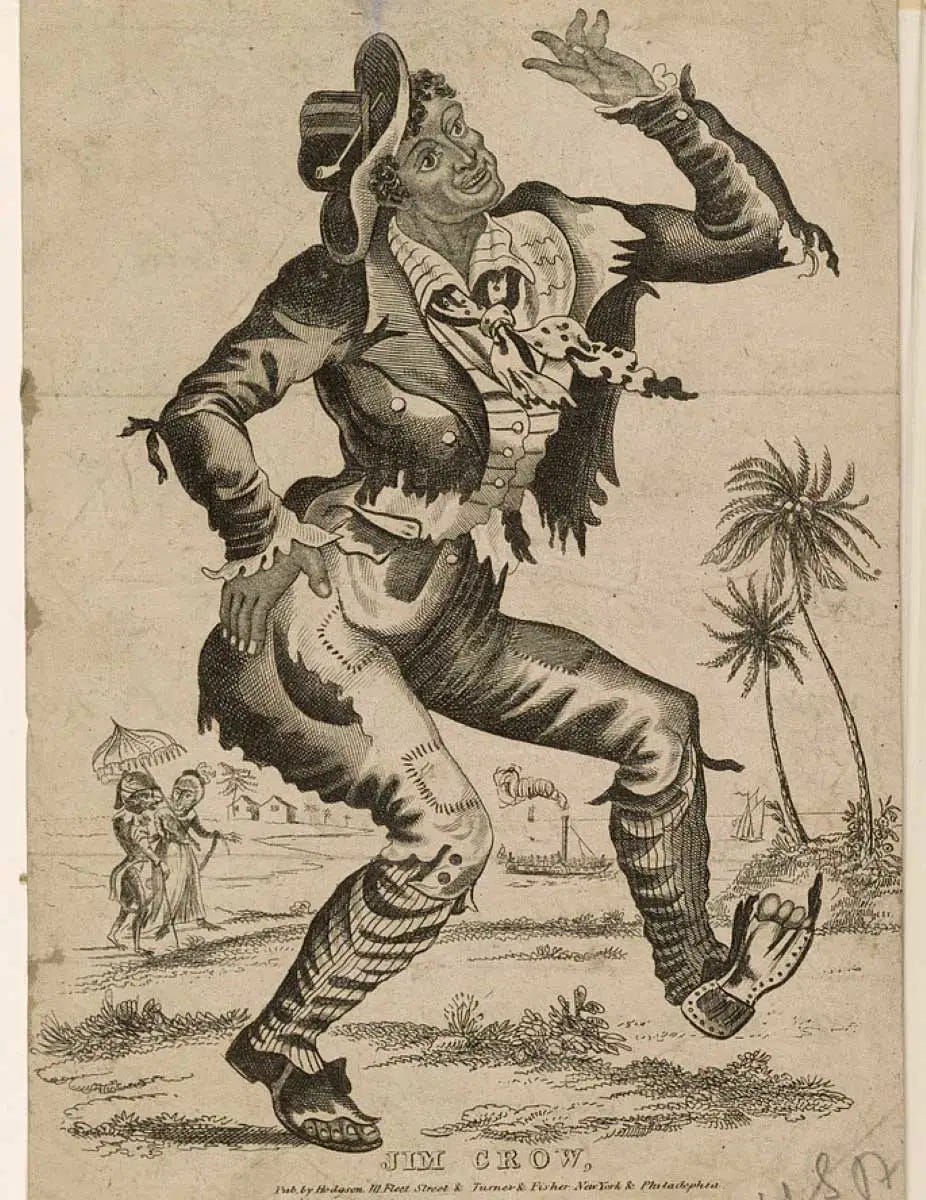

THOMAS “DADDY” RICE, 1828

Jump Jim Crow

Jump Jim Crow is a song composed by Thomas Rice for a Minstrel Show—a type of performance built on a racist caricature of Black people. The first edition of its sheet music, published by E. Riley, appeared in the early 1830s. The text was made up of “floating verses,” meaning stanzas or other adapted lyrics from other songs. Its refrain, for instance, is essentially identical to that of Hop High Ladies—better known as Uncle Joe.

It was not unusual for Black people to put on impromptu clown-like shows, alongside their songs, to entertain audiences. White minstrel performers then tried to copy these shows. The white founder of this style of entertainment was Thomas “Daddy” Rice, who introduced the emblematic figure of Jim Crow (after whom the later segregationist laws would be named) in the famous song “Jump Jim Crow.” We can consider this piece a sort of manifesto for the stereotypical image white people held of Black people:

Come, listen, girls and boys, I’ve just come from Tuckahoe;

I’ll sing you a little song, My name is Jim Crow.Wheel about, and turn about, and do it just so;

Every time I circle ‘round, I jump Jim Crow.I went down to the river, I didn’t want to stay,

But I found so many girls there, I couldn’t get away.I’m roaring on the fiddle, and down in old Virginia;

They say I play the scientific, like maestro Paganini,I cut so many monkey shines, I dance the galoppade;

And when I’m done, I rest my head on a shovel, a hoe, or spade.I met Miss Dina Scrub one day, I give her such a buss [kiss];

And then she turn and slap my face, and make a mighty fuss.

The other girls they begin to fight, I told them wait a bit;

I’d have them all, just one by one, as I thought fit.I whip the lion of the West, I eat the alligator;

I put some more water in my mouth, then boil ten loads of potatoes.The way they make the cornmeal fritters

In Virginia never tires;They take the dough, stick it on the foot,

And toss it in the fire.

THE ORIGIN OF JIM CROW

A LAYERING OF HISTORY AND LEGEND

It appears that the Jim Crow character traces back to a real-life episode observed by his creator, Thomas Rice, in the early 1830s in Louisville, Kentucky.

Rice himself recalled that one day while wandering through the city, he noticed a stable hand named Jim Crow who had a twisted leg and a deformed shoulder. The man was wearing torn clothes, and while he worked, he would perform dance steps and sing a song whose refrain went:

“Turn about, jump around, every time I turn about, I jump Jim Crow.”

Rice was captivated by this “darkie”’s style, and he realized that the little tune might appeal to an audience if he sang and danced in the same way. He then adapted the words, inventing additional new verses. One might say, for instance, that because Jim Crow was portrayed as irreverent “in-between” entertainment, there was no room for tears or frustration—crying did not befit a “Black man who thinks only of taking advantage of situations and indulging himself.” In short, there was no hint at deeper appetites or cunning, so his unreliability could be amplified for comic effect.

Beyond the undeniable influence of Rice’s personal experience, there is a good possibility that the figure of Jim Crow had existed for a very long time. In African traditions, including Yoruba culture from West Africa, there is a crow called “Jim.” And among enslaved people’s folktales that made their way to America, “Jim Crow” was a favorite trickster figure. Some enslaved people even adopted a Jim Crow–like stance as a way to cope with enslavement, using clownish or foolish behavior to avoid heavy labor.

Hoe cake literally means “hoe cake” (cornmeal fritters). The name comes from the fact that enslaved people cooked these cakes on the blade of their farm tools (in this case, a hoe) while they worked in the fields under the scorching sun, which was always available for heat.

From a technical standpoint, “Jumping Jim Crow” follows the pattern of folk songs referred to as all ye pieces—where the opening line invites people to gather and listen to the performer’s story. Many years later, Bob Dylan would use that same approach to begin “The Times They Are A-Changin’.” Over time, many singers performed “Jumping Jim Crow,” changing the verses and adapting them to address segregation in different ways. The African American poet Langston Hughes drew on that song for his poem “Merry-Go-Round,” in which Jim Crow is portrayed as the typical Black man forced to endure discrimination:

Where is Jim Crow’s place

on this merry-go-round?

Sir, I want to ride it, too.

Down South, where I come from,

Blacks and whites

can’t sit side by side.

Down South, on the train,

there’s a special car for Jim Crow.On the buses, they put us in the back—

but here, there is no back

to a carousel!

Where does the horse go

for a “colored” child?

Over time, in Black slang, “Jump Jim Crow” increasingly came to symbolize the strategy of evading segregation.

In 1845, the Christy Minstrels (for whom the great Stephen Foster wrote some of his most popular songs) debuted a show called the “Coon Show”, which soon became the template for nearly all other minstrel troupes. After an introductory “walkaround” showcasing all the performers involved, the musicians arranged themselves in a semicircle on stage, with the tambourine player (“Mr. Tambo”)—typically tall and lanky—on one end and the bones player (“Mr. Bones”)—often large—on the other. In the middle stood Mr. Interlocutor, serving as the emcee who kicked off the overture. After that, you got a variety segment of singers, dancers, and comics, often culminating in a performance of the “braggart Black man,” who, through exaggerated speech, ended up appearing foolish and ignorant.

STEPHEN FOSTER, 1849

Nelly Was a Lady

Drawing inspiration from those minstrel songs that depicted African American stereotypes—often called Ethiopian Songs—Stephen Foster wrote “Nelly Was a Lady” in 1849 and included it in his collection Foster’s Ethiopian Melodies. For the first time, a song managed to skillfully blend minstrel repertoire with a parlor ballad, thus fusing in one stroke all the ambiguities of these two musical styles: respectability versus rebellion, middle-class versus the obscene—and above all, the interplay between white and Black, offering the latter an anchor of hope in the face of unrelenting racism.

THOMAS “DADDY” RICE

THE FATHER OF THE MINSTREL SHOW

Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice (New York, 1808–1860) was an American actor and playwright who rose to fame around the mid-1830s through minstrel shows. In striving to appear as much like Black people as he could, he smeared his face with black makeup and emphasized certain features—like big red lips and a wide grin of extremely white teeth. In his shows—already quite similar to vaudeville—he interspersed songs and dances with colloquial banter in the typical slang of Black Americans. He became one of the most popular minstrel performers of his time, widely regarded as the “father of American minstrelsy.” The role that made him famous, “Jump Jim Crow,” turned him into the highest-paid minstrel performer of that era. In 1838, the Boston Post reported that “the two most popular characters in the world right now are Queen Victoria and Jim Crow.” Toward the end of the 1850s, Rice was struck by progressive paralysis, which soon ended his career, and he eventually took his own life.

Around 1870, Minstrel Shows hit their peak, to the point that Black troupes also started taking over the stolen formula. But while maintaining the classic cliché, they found a way to poke fun at white men by imitating their stiff, proud demeanor—highlighted especially in the grand ballroom dance known as the cakewalk.

The coon songs that were written for these minstrel shows—alongside the traditional repertoire from which Black musicians drew—became prime ingredients in the new style that many performers embraced. Indeed, by the end of the century, a fresh style had emerged, marking the early evolution toward more distinctively personal ways of performing.

A WINNING COMBINATION

Stephen Collins Foster (1826–1864) is widely regarded as the most important American composer of 19th-century popular song. Beside him stands the celebrated “Oh! Susanna.” He was strongly influenced in his youth by Dan Rice, an entertainer and clown who made a living with traveling circuses, becoming a prolific author despite his modest musical training. His career turned toward minstrel shows in the 1840s, drawing inspiration from those songs that depicted African Americans (the Ethiopians Songs). In 1849 he wrote enough of these to publish “Foster’s Ethiopian Melodies,” featuring “Nelly Was a Lady,” which the Christy Minstrels popularized with great success. This gave him the chance to join a significant social circle, eventually leading him to write songs like “Camptown Races,” “Nelly Bly,” “Old Folks at Home” (also known as “Swanee River”), “Old Kentucky Home,” “Old Dog Tray,” “Hard Times Come Again No More,” and “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair,” which earned him great fame, as they were performed in America’s most prestigious theaters. Nevertheless, he did not become rich; in fact, he died in poverty at the age of thirty-eight. At the time of his death, he reportedly had only thirty cents to his name.

“White minstrels drew on the true sense of rhythm, the ability to improvise, and the profound emotionality of African Americans.” — Emily Wellman (American Negro Minstrelsy)

JIM CROW AND “RACE RECORDS”

Progressives in the North rebelled against the ongoing violence faced by Southern Black communities and pushed for the Jim Crow Laws to be passed. These laws purported to guarantee equal rights to whites and people of color, although to be enjoyed separately. In reality, this was the prologue to segregation and the impossibility of Black emancipation.

The Jim Crow laws were local legal measures enacted in various U.S. states between 1876 and 1965. Their goal was to create and maintain the racial segregation of Black Americans and other non-white groups in all public services by establishing a “separate but equal” status. The principle of “separate but equal” initially presented itself as “equal but separate,” an innocuous switch of wording intended to align with the 14th Amendment. That amendment, at least on paper, guaranteed the same right to access public services for both Black and white people. Its openly stated aim was to minimize contact between the two races, creating a form of segregation that distanced Black people from the white world.

Schools, hospitals, prisons, and other public services were required by law to operate under the same efficiency for all, in the spirit of Jim Crow’s racial separation. In practice, however, that never happened, as facilities for Black people were almost always of far inferior quality to those for whites. A large portion of Black schools, for instance, received far less funding per student compared to nearby white schools. For the time being, segregation was chiefly a Southern phenomenon; in Northern states it had not been legally enforced. Even so, a clandestine system of de facto segregation grew concerning public education, where white families generally refused to let their children attend school with Black children.

The introduction of Jim Crow laws began in Florida, which returned to a Democratic government following the Civil War. In 1887, they instituted segregation on trains, with separate compartments for Black and white passengers. Louisiana soon followed, extending these distinctions to “white,” “Black,” and “colored” and thus also banning “mixed” travel under threat of fines.

In 1896, following the infamous ruling of the Plessy v. Ferguson case—in which a citizen of New Orleans was deemed guilty of “blood contamination” and barred from sitting in a certain train car—segregation in rail travel was further entrenched and then spread to each state, taking the form of increasingly strict and discriminatory laws. That ruling effectively established the legal foundation of the Jim Crow era.

From 1891 onward, Democrats controlled Southern state governments. Endorsed by the Supreme Court, which systematically denied appeals against these laws, they began to conceive new and increasingly broad types of separation—focusing especially on banning Black people from sports, religious activities, and other public functions. Little by little, Jim Crow began applying to the separation of Black and white people in schools, public places, and public transport. Restaurants in certain cities or towns often strictly segregated dining rooms, one for whites and one for Blacks. Even within the military, racial segregation was enforced.

Woodrow Wilson, a Southern Democrat elected president in 1913, further promoted Jim Crow laws by installing many politicians in his government who staunchly believed in segregation, effectively extending racial segregation into federal offices. Over time, alongside the laws that prevented Black people from voting, a series of “private” regulations (in businesses, in parties, in labor unions) spread, barring Black people from, for example, buying homes in certain neighborhoods or seeking employment in certain stores.

“THE BIRTH OF A NATION”

APOLOGIA FOR THE WHITE RACE

In 1915, director D.W. Griffith made “The Birth of a Nation,” based on a novel by pastor and playwright Thomas Dixon. The film, lasting over three hours, recounts events from the American Civil War through Secession and Reconstruction. Possibly more than it consciously intended, the film had a conspicuously racist tone that endorsed the injustices of Reconstruction, implying a “truth” that Blacks weren’t fit for freedom.

In the story, Gus—a Black man—pursues a white girl who leaps to her death to avoid being assaulted. Her brothers, incited by the Ku Klux Klan to exact vengeance for her death and, in general, to defend white supremacy, lynch Gus brutally, leaving his body hanging from a tree. In the “North,” some propose to retake control of local government through armed interventions, while in the “South,” such scenes of lynching had already been part of daily life for years. The film’s depiction—the woman’s suicide, the Klan’s vengeance, and so on—provides an apology for the Ku Klux Klan, going so far as to present an image of a naive Black man on a runaway horse. This led to protests from many. Griffith wanted to suggest that Black people were unreliable and had to be contained by any means. President Woodrow Wilson, during a private screening of the film, famously said: “It’s like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it’s all so terribly true.” In public, he distanced himself and labeled it an “unfortunate production.”

Between the Civil War’s end and the 1930s, the most significant new musical genre to emerge among African Americans was the blues, which would become the cultural hub for Black expression. Before the blues took shape regionally, it stemmed partly from the same traditions as the spiritual, work songs, and hollers, as well as other early forms. Enslaved people had invented these forms to pass the time while laboring on plantations. The difference from the spiritual is that the blues is essentially a secular matrix (i.e., not religious) that speaks to very personal, existential, and sometimes even social issues. Through the lyrics of these later pieces, we glean crucial insights into everyday life for Black people in those years: anguish, discrimination, and more.

So this was not music born of resignation. On the contrary, it derived from the possibility—no matter how slight—of detachment, of forging one’s own path. The small joys Black people can access—like sex, alcohol, or wandering around with a guitar enabling them to live on tips—are precious forms of self-expression. The blues is the first musical expression by formerly enslaved people that speaks of their experience, describing an unending search for place and recognition and, ultimately, the possibility of forging a living either in legitimate work or simply by vagabonding. They were forced into a precarious situation, perpetually at risk under Jim Crow laws. To get drunk, to go out and have fun in the city or attempt to organize among young women who might protect them—these could be the same choices that many impoverished white people made, albeit within narrower bounds because of the intense racism that forced Black people to act covertly.

Many blues songs were deliberately conceived as social critiques, though such topics still spark debate. Blues lyrics often become a powerful vehicle of denunciation: speaking about one’s condition and poverty is undeniably a way to highlight publicly the deep discomfort in which entire generations lived. The rural South was not the only stage for these complaints—workers in Northern industries also faced an exploitative class system. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), with their revolutionary program, included many working-class voices, but in old Confederate strongholds, it was mainly narratives by Black people that offered no respite from difficulties, at times urging, “We must continue living, even in a moment of danger or despair.” This stigma of the American system preyed on the weakest. In the same way, Black people tried to fend for themselves, waiting for better times and seizing every opportunity that arose.

“Every morning, Lord, the rent collector comes to the door / And if my man doesn’t work, Lord, it’s two or three weeks or more”— Charley Patton, “Mean Black Moan”

Musicians in particular realized how vital it was to build an eclectic repertoire that could satisfy all sorts of audience requests. To earn tips, they had to be able to play in any context: whether at parties, dances, or simply on a street corner for a diverse audience with varied tastes. Black musicians thus needed to know how to play not only blues but also the hits of the day, as well as some songs from white traditions, if those were requested.

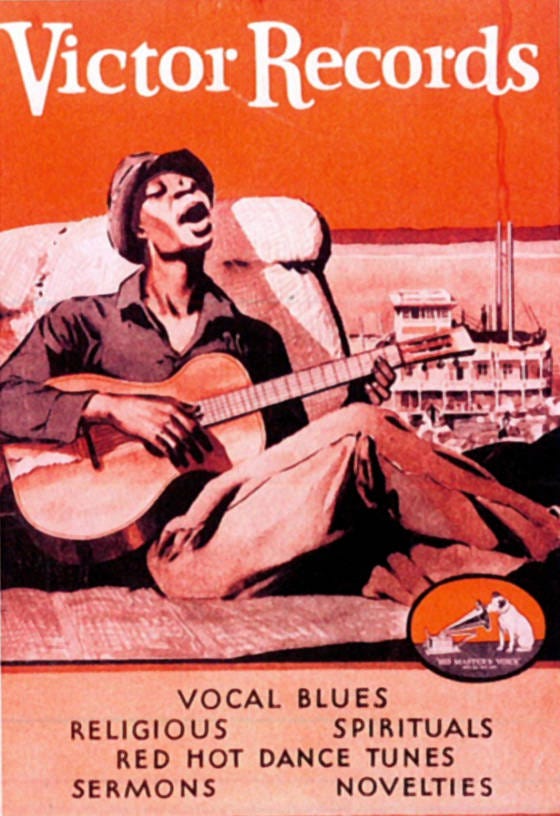

Among the artists of the 1920s and ’30s, we now only know those who managed to record because only those recordings remain. It’s really the record producers of the time who came to grasp the sales potential and attempted to emulate the big successes that early blues performers were achieving. In line with the Jim Crow laws, record companies invented “Race Records,” intended for a Black-only audience, failing to grasp that art is universal. They also didn’t foresee that many white people would start discovering and taking an interest in this music—thus, for the first time, cracking open the door to segregation, at least in the cultural marketplace.

The bluesmen who did manage to record constituted a small, fortunate minority compared with the broad musical scene flourishing in the countryside back then. Many of them are likely among the most talented in circulation, though there are certainly plenty of others who were just as good, who never got the chance to become known.

Charley Patton

One of the earliest well-known blues musicians, Charley Patton had an extraordinarily varied repertoire, ranging from the most classic, introspective Delta blues to pre-blues compositions drawn from Black folk and minstrel sources. These share nothing with the grotesque minstrel stereotypes that white musicians later depicted on stage.

Blind Blake, 1929

Police Dog Blues

Recorded in 1929 in Richmond, Indiana, by Arthur “Blind” Blake for Paramount, the song—like the rest of the Florida musician’s discography—features remarkable fingerpicking. “Police Dog Blues,” revisiting the theme of wandering, focuses on unrequited love: the singer breaks things off to avoid having the woman set her fierce mastiff on him. Forever on the edge between humor and tragedy, Blake thus shaped his own stylistic path. It’s the other side of the coin from the anguish and torment found in Robert Johnson’s music.

The lyrics of his blues songs are wide-ranging, addressing both deeply personal feelings and the events around him. In “High Water Everywhere,” for example, he writes with awareness about the devastating Mississippi River flood of 1927, like a sort of news bulletin on the disasters it caused in the Delta and how people rushed to find a dry spot to settle.

In “Mean Black Moan,” instead, he speaks of the railway strikes that swept Chicago in the late 1920s, lingering on the survival difficulties of those workers, while in “It Won’t Be Long,” he doesn’t hesitate to delve into rather grim details—talking about the habits of the people of Minglewood and offering his advice to spend time in more permissive areas like nearby West Memphis, Arkansas, where the prostitutes were considered much better than elsewhere. This blues number delivers a significant snapshot not only of the place itself but, in all likelihood, of a large portion of the Black community in the South, where earnings are mostly off the books and “forbidden” pleasures represent the best opportunities to be exploited.

RACE RECORDS

“Records of the Race”

In 1920, Black songwriter Perry Bradford convinced an executive at Okeh Records to record the very first blues disc ever—featuring Mamie Smith, a singer performing with a jazz orchestra and already enjoying moderate success among African Americans. No one expected that the 78-rpm “Crazy Blues / It Is Right Here for You” would sell 75,000 copies in just a month.

From that moment on, Okeh Records ramped up its production of blues records. Competition wasn’t far behind: Columbia and Paramount likewise began deploying agents to the Southern countryside, tasked with recording new talent in the field; Vocalion followed suit. Each of the major labels created a commercial category of its own—“Race Records”—to slot Black artists’ releases into.

In 1921, Black producer Harry Pace founded his own label, Black Swan, which managed to put five hundred records on the market each year, aiming to free Black performers from white monopolies. He held on for three years but was eventually forced to sell everything to Paramount. By then, though, the production of blues discs had already been swept up into a powerful distribution chain that never looked back.

Charley Patton, in short, was a musician able to encapsulate all manner of life’s situations in his blues—the daily rhythm of his community—and sing them in a way that expressed feelings and possibilities shared by all who listened. Thus we arrive at Robert Johnson, Son House, and all the other founding fathers of this musical genre. Each one naturally favored the themes closest to them—rarely the ones outside their specific world. In their own way, blues musicians became the folk philosophers of their time, much like the griots before them (in Africa), and like future folk singers would be. The storytellers on the losing side of society—those who managed to blend into their blues an understanding of power dynamics—did so under the weight of prejudice or simply because no one bothered to pay them any mind.

“I have a kind-hearted woman who does everything in the world for me,

but other evil women won’t leave me alone.” — Robert Johnson (Kindhearted Woman Blues #2)

BIG BILL BROONZY

Black, Brown and White

Big Bill Broonzy first recorded “Black, Brown and White” in 1951, by which time he was already an established musician based in Chicago—his chosen city after spending his childhood in Mississippi. Even in his youth, he never forgot the hardships he had to endure: racism and discrimination enforced by the Jim Crow laws, which forever placed Black people at a disadvantage compared with whites.

Those recollections crystallized in a song, “Black, Brown and White,” which, with biting irony, recalls what happened to him whenever he tried to get a job:

This little story I’m telling you folks, you know that it’s true /

If you’re Black and want to work, here’s what they’ll say to you: /

If you’re white, it’s all okay /

If you’re brown, stick around /

But if you’re Black, brother, get back.

That track, initially included on the album Big Bill Blues, went on to become a classic, later featured in the compilation Trouble In Mind (Smithsonian Folkways, 2000). Martin Scorsese famously recalled it, using it on the soundtrack for Mike Figgis’s film Red, White and Blues.

ROBERT JOHNSON, 1936

Crossroads

Recorded in 1936 during Robert Johnson’s first session for Columbia in San Antonio, Texas, “Crossroads” gradually became a standard for all seasons. Its themes—wandering, bondage, and superstition—are fundamental to the blues. In a deserted crossroads in the countryside, Johnson recounts meeting Satan and forging a now-famous pact in which he sold his soul in exchange for extraordinary guitar skills.

STRANGE FRUIT

THE SHAME OF LYNCHING

The fruit of segregation is the tacit acknowledgement of racial difference. Imagined white superiority ensures that, in any situation, Black people can be singled out as scapegoats for any wrongdoing—and can be subject to vigilante “justice.” Lynching is the sorrowful result.

From the end of the Civil War onward, lynchings took place at ever-higher rates, predominantly targeting Black victims. When people of color gained the right to vote, many whites feared that their racial supremacy was in real danger. In many Southern counties, African Americans formed a large majority of the population—enough to elect Black politicians who might threaten white interests.

As early as 1866, the Ku Klux Klan was founded, making Black abolitionists (and white people who supported them) its principal target. Over the ensuing decade, paramilitary groups arose with the aim of preventing Black citizens from voting. In the post-Reconstruction era, as old privileges were lost and economic woes escalated, African Americans in the Southern countryside—many of them formerly enslaved people working as sharecroppers—became the easiest scapegoat for every problem. The resulting violence soared to levels never seen before. White farmers who could not handle competition sometimes found brutal solutions: at harvest time, to avoid paying them, they might simply murder the Black sharecroppers, claiming that parasites (like the dreaded boll weevil, which countless blues songs mention) had ravaged the crops—thus reneging on the wages altogether.

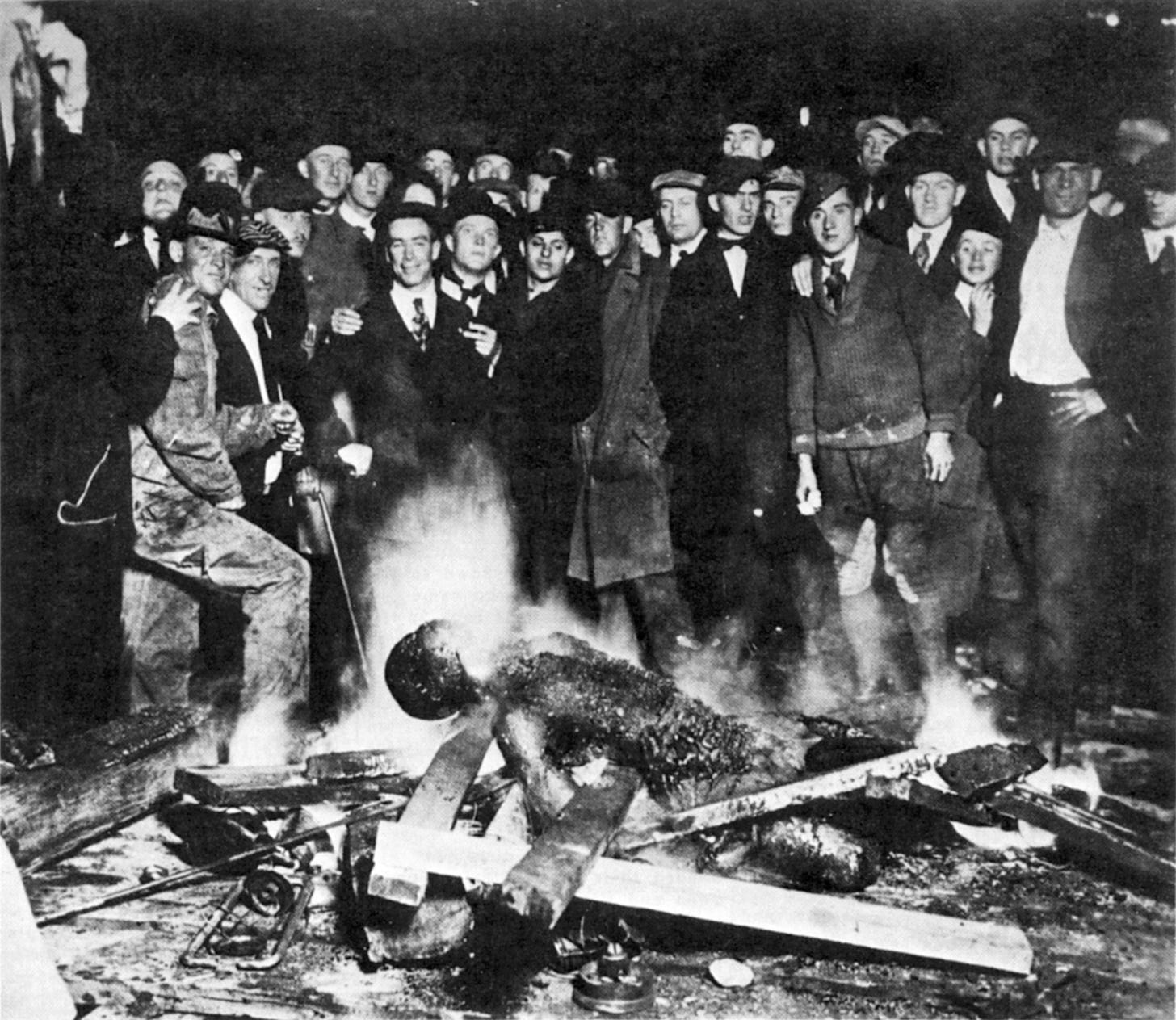

It’s hard to fully gauge the extent of lynchings carried out by white people to rid themselves of the “hated negro” because the exact number depends on how each incident is labeled. According to Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, between 1882 and 1968 there were 3,446 recorded lynchings of Black people (peaking annually between 1890 and 1910), a period in which the post-war economic crises were at their most acute. Mississippi takes first place with 581 victims, Georgia second with 531, and Texas third with 493. Lynchings—often preceded by torture, mutilation, and subsequent burnings—rose steadily between 1890 and 1920, amounting to an average of one lynching per day.

“Watch that boll weevil, keeps moving along, you can plant your cotton,

but you’ll never pick a thing.” — Boll Weavil Blues

One of the most common pretexts for lynching was the “protection of white women.” Yet that factor was only the third most frequent cause cited, after “homicides,” whether real or presumed and “all other reasons,” a catch-all term to denote the daily insults and assaults that Black people regularly endured.

These crimes met resistance from many progressive citizens—particularly intellectuals and journalists—who did everything possible to inform the public of these atrocities. Yet, they continued almost entirely unpunished by racist local justice systems. The federal government was criticized for its lax attitude toward questioning sheriffs who routinely ignored the violence or even attended the executions themselves. Despite widespread press campaigns to mobilize central authorities, nothing changed. Between 1882 and 1968, 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress—seven U.S. presidents endorsed them after they passed the House. But it was all in vain. The reactionary faction of Southern Democratic senators—known as the Solid South—always blocked it.

When, from the 1950s onward, the Democratic Party leadership began to embrace Black emancipation, some white voters in the South turned away, deciding to support the Republican Party. Seizing the opportunity, Republicans adopted what came to be known as the “Southern Strategy,” ushering in a new political phase that continues to this day.

SOLID SOUTH

THE OLD STRONGHOLD OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY

The phrase “Solid South” denotes the solid bloc of Southern states whose electorate supported the Democratic Party for a long period—roughly from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 to the rise of mass movements for African American civil rights in the 1960s. The Democratic Party, having become fully aligned with white supremacists, was the main political force in those states, to the point that the term “Solid South” often refers to the near-total uniformity of electoral results there.

Segregation, emerging from Jim Crow laws, was declared unconstitutional by federal judges who argued it violated the 14th Amendment, as it failed to ensure equal treatment in the distribution of public resources. Still, it fostered a powerful sense of solidarity among Southern whites—one that increasingly erupted in violence and, all too frequently, lynchings.

Lynching, whose name comes from Judge Lynch, is a relic of the old frontier, where it was common for (usually guilty) suspects to be tried by the crowd before they ever appeared in front of a legitimate judge in a nearby town—regardless of whether the accused was innocent or guilty. They were punished like livestock thieves or drifters, sometimes murdered by hanging or gunfire. Lynching was often a convenient way of eliminating an economic competitor who didn’t belong there or who bothered whomever claimed a higher position or wanted to expand their holdings. The wild, brutal frontier that “does things its own rough way,” without scruples, was quite capable of taking justice into its own hands in cases of real or perceived wrongs. Even though many episodes from that wild frontier have become part of the mythology that’s now deeply woven into Southern culture, problems persist in removing old antagonisms, whether they concern Indigenous people, immigrants treated like beasts, or anyone who doesn’t fit in.

On March 14, 1891, in New Orleans, an angry mob stormed the jail and lynched eleven Italian immigrants (the so-called “dagoes”), all suspects in the killing of a policeman.

Bluesmen—the chroniclers of everyday life who speak about these truths in their songs—describe lynching in the blues as well, turning lived events into ballads that filter through popular music. Leadbelly, considered one of the greatest exponents of this style, had quite a few songs in his repertoire that spoke of lynching and summary justice. He knew prison life firsthand, including numerous stints when he risked conviction—and even once nearly killed a man. It’s no coincidence that the characters in his music often face the same fates. Tracks like Stack-o-Lee, John Hardy or Frankie and Albert revolve around themes of depravity and murder: the guilty person is arrested, condemned by a single judge’s verdict, or lynched on the spot. This is just a small sampling of that powerful storytelling tradition, also common among white folk musicians. Indeed, the genre of “murder ballads”—for example, the tale of someone who kills his beloved (often nearly a wife) because she refuses to give in—derives directly from white folk tradition. From The Banks of Ohioto Lily of the West, branching into Tom Dooley, these songs describe real atrocities that must have been all too frequent in a less regulated rural society.

In the early 1900s, once a large segment of menial laborers—mostly Black people—were hired to dig sewers or lay railroad tracks and ties in new lines, the workforce was composed predominantly of African Americans, who were easy scapegoats whenever times got tough. They were simultaneously “accused” of stealing technical skills from white workers.

Mississippi John Hurt, who was discovered by “race record” producers in the late 1920s, lived certain harsh realities of the South. He included in his repertoire songs like Louis Collins and First Shot Missed Him, which prove how swiftly vigilante justice could strike. Because it was nearly impossible in that era for record labels to imagine releasing a bluesman’s songs about killing white people, that musician had to find other ways in the white folk tradition to express how people took justice into their own hands—sometimes turning a blind eye while innocent blood was shed, a practice that remained frighteningly normal. It’s easy to see how violence in the South could still appear “normal,” how lynching could be carried out in a public square and even turn into a grotesque “spectacle,” with an entire crowd gathering to photograph the event—afterward selling postcards as souvenirs. One event that helped inspire Abel Meeropol, a Russian-Jewish teacher from the Bronx, to write the poem “Strange Fruit,” which later became the famous song recorded by Billie Holiday in 1939.

MISSISSIPPI JOHN HURT, 1928

Stackolee

Frontier violence carries countless contradictions that Western films have exploited a thousand times. A crime, a theft, or even a gambling loss to a card cheat often ended in a summary lynching before a judge could arrive to question witnesses. The Stackolee of legend is basically a “bad man” or, more precisely, a malicious man who kills poor Billy the Lyon solely because Billy ruined his Stetson hat during a poker game in a saloon.

“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” — George C. Wallace (Governor of Alabama)

THE LYNCH LAW AND VIGILANTE “JUSTICE”

A fearless advocate of American independence from the British crown, Charles Lynch served as a militia colonel during the conflict, developing a fierce aversion to the “loyalists,” those who sided with the monarchy. When the then-governor Thomas Jefferson asked for clarification regarding certain alleged collaborators and traitors, Lynch didn’t wait for a proper trial. He sentenced them to the gallows without waiting for due process. Protests were quickly silenced by the General Assembly (which soon became the state legislature) because, given the urgency, everyone justified the judge’s behavior. By 1796, lynchings—summary executions—had become part of American frontier culture. It was typically carried out on thousands of people accused of robbery, abuse, rape, murder, and so forth. Any hint or denunciation was enough, and “Judge Lynch,” without setting up real courts, struck like a guillotine to settle a quarrel or confirm an accusation.

During the century that followed, lynching evolved sinisterly: after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery in the Southern states, it became a common practice targeting African Americans, singled out by white racist “surveillance committees.” People no longer waited to confirm if a person of color was truly guilty; Black suspects were arrested at home and dragged into the nearest woods or even into a public square to be hanged. Many private citizens, fired up by organized militias like the Ku Klux Klan, joined forces to mete out swift “justice.”

Southern trees bear strange fruit Blood on the leaves and blood at the root Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

BILLIE HOLIDAY, 1939

Strange Fruit

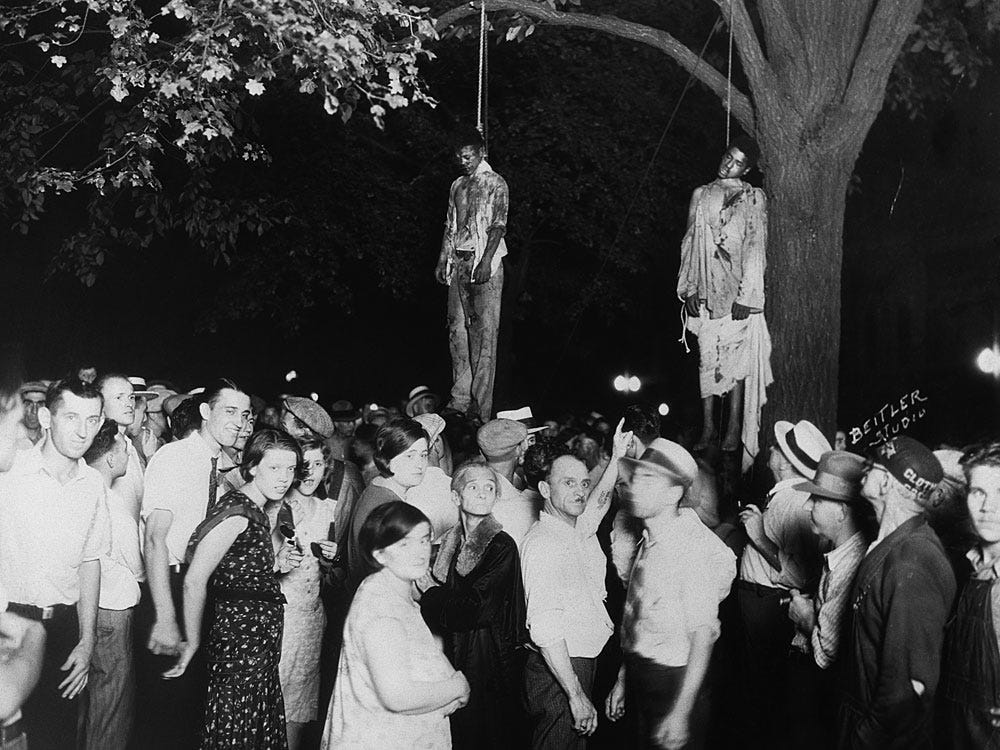

Billie Holiday first performed “Strange Fruit” in 1939 at New York’s Café Society—a venue where Black and white patrons could freely mix. From that point on, the song became her signature while also marking the start of her troubles with the FBI. Written a few years earlier by Abel Meeropol in response to a harrowing lynching in Marion, Indiana, “Strange Fruit” serves as a metaphor depicting Black bodies hanging from tree branches—a searing musical indictment of racism.

“Strange fruit” quickly became a phrase synonymous with lynching. The “strange fruit” is the body of a Black person swaying from a tree. Holiday’s unapologetic social activism confronted these realities head-on, undeterred by FBI reprisals that followed her for the rest of her life.

Southern literature of that era also shed light on the rampant violence toward Black people in rural communities. Major Southern writers like William Faulkner and Erskine Caldwell, born between the late 1800s and early 1900s (along with younger authors like Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor), chose instead to focus on the struggles of impoverished white people—though the plight of Black people often served as a dark mirror in their stories. They seldom made Black characters the main protagonists, but they still hinted at the terrible oppression inflicted on them. In Caldwell’s Tobacco Road, for example, there’s a lynching scene reminiscent of those photos later used by Abel Meeropol—and in Faulkner’s Light in August, a male character is tormented by the racial hysteria of the South, forever unsure whether his own blood is truly “pure.”

STRANGE FRUIT

A SONG BORN FROM A PHOTOGRAPH

Lawrence Beitler took a chilling photo of two Black men, Thomas Shipp and Abraham Smith, being lynched after accusations of murdering a white man and raping his fiancée. The scene took place in Marion, Indiana, on August 7, 1930. A crowd of about five thousand people—men, women, and children—gathered to watch this grim spectacle, eagerly and smugly witnessing that act of “popular justice.” The two accused had been taken from the city jail by a raging mob wielding clubs. After beating them, the mob lynched them from two poplar trees. When Abram Smith tried to get loose from the rope, they pulled him down again to break his arms so that he couldn’t struggle. Among the mob were also police officers who, instead of protecting the prisoners, actively abetted the lynching.

Beitler’s photograph was not sold out of compassion; he developed and sold thousands of copies, pocketing a tidy profit. The young woman who was allegedly raped in the incident never confirmed the accusation.

Years later, in 1937, one of these photographs reached Abel Meeropol, an unknown Jewish schoolteacher from the Bronx who had long pondered how to respond. Under the pseudonym Lewis Allan, he composed a poem suggesting lines and images that ultimately formed “Strange Fruit” as a song with exactly that title. In 1939, Billie Holiday made the track her own version—a tremendous symbolic indictment that would resonate worldwide. Since then, the piece has been covered by Nina Simone, Dee Dee Bridgewater, Bettye LaVette, and many others.