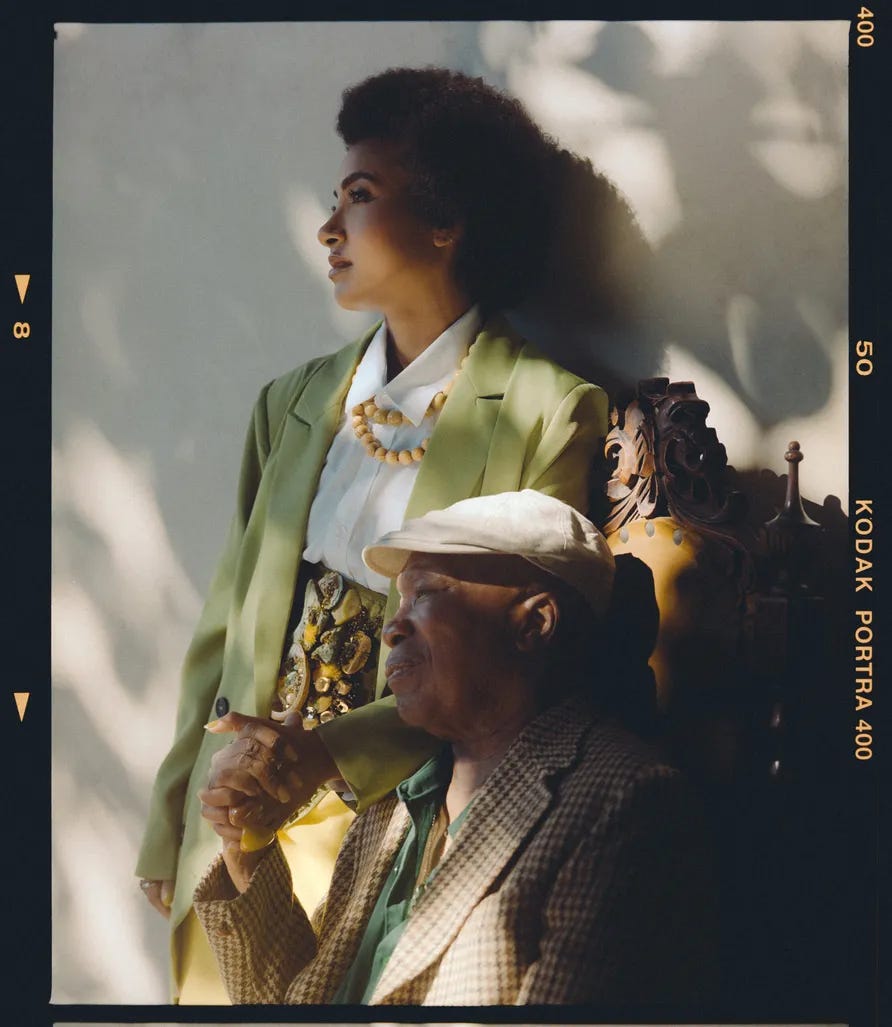

Milton + esperanza: The Tone Wavers, But It’s Right

Fragile yet unbroken and touching, Brazilian pop star Milton Nascimento succeeds in creating conversational late-career work with jazz acrobat esperanza spalding.

80 is a sound barrier for any voice. With men, you often hear it even better than with women because the jump seems bigger from lower ranges to the age-related higher ones, where the voice begins to break. You can hear this fragility more and more in the speaking voices of Joe Biden or Paul McCartney, both born in ‘42. So how must it feel for the 81-year-old Brazilian Milton Nascimento, who has been a pop star not only in his home country since the late sixties and for a long time easily tumbled over several octaves, from a caressing baritone to a super-high falsetto? What does the so-called late work of this man sound like? And is it such a good idea to realize it with a jazz acrobat like the American singer, bassist, and arranger esperanza spalding? Will her presence cover up the age? Or will it bring out the fragility in Nascimento’s aged voice?

The simply titled album Milton + esperanza gives many answers to this and remains, despite all bows, to Nascimento, a work by spalding. She wrote most of the songs she produced, played, and sang with her band. Only five of the 16 songs are by Nascimento, and four of them are old compositions. But spalding’s hyper-musicality and self-confident appearance are not disadvantages. She takes her idol by the hand and reaches heights with him that were no longer expected. Even cover versions that initially seem odd, such as Michael Jackson’s “Earth Song” or “A Day in the Life” by the Beatles, channel Nascimento’s understanding of oceanic music. Even in those moments when you can barely hear him.

Sometimes spalding, whose Portuguese sung by even native speakers attests to having an amazingly accent-free quality in early YouTube comments, also holds back. Nascimento wrote the duet “Um Vento Passou” for his old friend Paul Simon, in which the bassist becomes a minor character. What the two singers whisper to each other, full of love and respect, must be heard, not only because Simon also puts so much effort into the Portuguese.

The admiration for Nascimento has been great since the mid-seventies among all those US stars who wanted to expand their original styles: Simon was one of them, as was Carlos Santana, who came from Mexico. However, musicians Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter, who were always looking for broad appeal, recognized Nascimento’s appeal the fastest. The adopted Black child of white academics effortlessly exuded what the extreme jazz musicians longed for at his best times: to be popular but never dull, light but always complex. How nice that these gifts can be heard once again on Milton + esperanza, even if the packaging now looks quite different than in the seventies.

Highlights are four old songs from Nascimento’s time between 1967 and 1975. This is, of course, due to the source material but also to the special care with which Spalding rearranges it. Nascimento last played the acoustic guitar long ago; two years ago, on his farewell tour, he sat without an instrument on a chair in front of the microphone; the last album is nine years old. He’s left with this voice, which Spalding recorded just over a year ago, mostly in Nascimento’s house in Rio de Janeiro when he wasn’t watching telenovelas, as she says. Already, the first song, more than 50 years old, conveys why Nascimento is such a great artist and how cleverly spalding handles his legacy.

The song “Cais,” roughly translated as pier or landing stage, originally comes from the 1972 album Clube da Esquina, revered as a masterpiece among nerds. Many myths exist about the eponymous club in the southeastern state of Minas Gerais; it’s considered a place of networking, a street university, and an incubator for musical ideas. On Nascimento’s album, created by songwriter Lô Borges, it sometimes sounded like bossa nova, sure, but also like British pop and European piano music. Tonally, everything strives for openness, and the arrangements like to change course. The pier that Cais carries in its title was to be understood metaphorically more than 50 years ago: “I invent the pier, and I invent much more,” Nascimento sang. In a military dictatorship, which Brazil was until 1985, this sounded like an encoded escape fantasy. But Cais is still a protest song without a clenched fist in 2024, a seductive nod to a better place: to art.

The new version of “Cais” opens with a short acapella duet with spalding. Nascimento sings his lines without artificial sound patches, then spalding joins an octave higher; first, strings accompany the song, like the wind coming from the sea. After two minutes, both voices hold a long note while the piano and guitar are already introducing new forms until the outro begins much too early. spalding packs an enormous amount into three and a half minutes; everything is becoming searching and turning, and nothing seems heavy. You can’t capture Nascimento’s art better than this. This song alone made the album worthwhile.

Also, in the song “Outubro,” which comes from the late sixties and, like so many in Nascimento’s work, deals with personal loneliness and political isolation at the same time, Spalding condenses a lot in a small space. She sends the intimate piece to Broadway and back to a jazz club on the beach. Moreover, she never pushes Nascimento more consistently to his vocal limits than here. Not for a second does it sound embarrassing because the tone is right, even if it wavers a bit.

The only thing missing is a guest appearance by early fan Herbie Hancock. He, too, is now 83 years old and at least present in spirit when a number by Hancock’s companion Wayne Shorter, arranged in the style of spiritual jazz, sounds as the closing piece. Shorter’s widow Carolina, née Dos Santos, sings along in “When You Dream.” She and spalding lay out a carpet for Nascimento, which the master only occasionally steps on, far back in the soundscape. This restraint is also part of the freedom that Milton + esperanza conveys.

To understand this freedom, you must take the album title seriously. Between the first names is a plus sign, not a marrying conjunction like “and.” Dialogue doesn’t mean that both speak equally and equally loudly. Communication can also mean having a conversation that respects the uniqueness of the voices and adds them precisely because of their differences rather than making them conform to each other. This way, no one has to deny themselves: neither the woman at the height of her abilities nor the man at the end of his art. Music can hardly propose more than this.