Milestones: Like Water for Chocolate by Common

Common’s LWFC is a masterpiece. It nods to the Afrocentric lineage of its influences—Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat presence, Roy Ayers’ jazz-soul fusion, and the spiritual resonances of Nina Simone.

When it comes to hip-hop landmarks in the United States, Chicago often stands just behind the towering reputations of New York and Los Angeles. Yet, the city has brewed its own potent style and rhythm since the start. By the late 1980s and early ’90s, Chicago’s South Side was pulsating with schoolyard ciphers, block parties, and a new generation of young MCs eager to channel the everyday realities of their environment.

Growing up on the South Side meant being surrounded by a rich embroidery of gospel, blues, jazz, and soul. This cradle of African-American musical tradition was nearly unavoidable for Lonnie Rashid Lynn Jr.—the artist we know as Common. Walk down 79th Street on a sunny day, and you might hear Al Green crooning from an open window or the raw grit of blues wafting from a local juke joint. This sonic diversity laid the groundwork for his broad-minded approach to hip-hop: poet, philosopher, and B-boy purist.

Common’s career trajectory started modestly in 1992 with Can I Borrow a Dollar?, released under the moniker Common Sense. At that time, hip-hop was in a state of flux, straddling the line between the playful exuberance of the late ’80s and the raw gangster realities introduced on the West Coast. On his debut, you could sense Common was still finding his footing, leaning on a comedic, tongue-twisting style with clever punchlines. The album didn’t exactly blow up commercially, but it became an underground favorite, laying the groundwork for what was to come.

By 1994, Resurrection pushed him further into the public eye—especially with the track “I Used to Love H.E.R.,” which remains one of the most iconic hip-hop love letters. The song cleverly personified hip-hop as a woman he once adored, now drifting into commercialization and gangster tropes. Instantly, Common was labeled the “conscious” rapper who lamented the genre’s shift in tone.

His growth continued through 1997’s One Day It’ll All Make Sense. This album felt like a coming-of-age diary—he rapped with vulnerability about fatherhood (he became a father during this period), spirituality, and family ties. Though One Day… garnered critical acclaim, it was still considered niche outside of the East Coast’s underground fanbase and Chicago’s loyal pockets of support. But it gave a hint that Common was on the cusp of something bigger—a transformation that would soon find its full bloom in Like Water for Chocolate.

As the 1990s rolled on, the East Coast/West Coast feud intensified, and gangster narratives, flashy aesthetics, and the rise of massive labels like Death Row and Bad Boy dominated rap albums. Yet beneath that glossy mainstream surface, a new wave of “alternative” or “conscious” hip-hop was forming—led by acts like A Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, The Roots, and, eventually, Common.

When Y2K hit, Common and other torchbearers for thoughtful lyricism found themselves in a unique position. The public was growing slightly weary of the Puff Daddy-era sparkly suits and dominating pop flair. There was an appetite among a core group of fans for a more organic, soul-rooted sound. Common’s next album would tap into that moment perfectly, bridging the gap between old-school devotion and new-school explorations. The timing was right—and thanks to a collective of equally passionate, boundary-pushing artists, Like Water for Chocolate would arrive as a statement piece for a new millennium.

The cultural landscape was in a state of flux. Y2K hysteria had faded into a collective shrug, leaving people eager to embrace the next big thing. This era saw the dot-com bubble, where Silicon Valley millionaires seemed to sprout overnight, and Napster was reshaping how music reached audiences, disrupting record labels and reshuffling priorities in the industry. Suddenly, the internet was no longer a novelty but a tool that could connect artists and fans in new, occasionally messy ways.

Chicago, Common’s hometown, had always been a musical mecca: the blues clubs and jazz dens of the South Side left indelible marks on the city’s cultural DNA, while house music revolutionized dance floors around the globe. By 2000, hip-hop from Chicago was gaining traction, although it wasn’t yet the juggernaut it would become with artists like Kanye West, Lupe Fiasco, and Chance the Rapper. Common was a central figure in that shifting identity, representing a city that was simultaneously steeped in tradition and itching to break new ground.

Politically, Chicago was navigating issues of racial inequality, police brutality, and economic disparity—themes that inevitably bled into Common’s lyricism. The city’s legacy of political activism loomed large. From Fred Hampton’s Black Panther movement in the 1960s to Harold Washington’s pioneering mayoralty in the 1980s, Chicago had long been fertile ground for outspoken community leaders. Common’s own father (a former ABA basketball player and youth counselor) had instilled in him a sense of civic responsibility, and that outlook colored the social undertones of Like Water for Chocolate.

At the dawn of the new millennium, hip-hop’s identity was torn between commercial success and artistic purity. Superstar rappers like JAY-Z, DMX, and Eminem dominated the charts, while underground icons like Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and MF DOOM catered to listeners craving more adventurous or conscious content. Common straddled both worlds: he had gained critical respect as an astute lyricist and soulful storyteller, yet he was also flirting with bigger platforms and cross-genre collaborations.

Ask any serious music head about the late ‘90s to early 2000s “Neo-Soul” movement, and you’ll inevitably hear about the Soulquarians—a loose collective of musicians, producers, and vocalists who congregated in New York’s Electric Lady Studios to forge a fresh, genre-blurring sound. The core group included drummer extraordinaire Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, producer/MC James “J Dilla” Yancey, multi-instrumentalist James Poyser, and visionary artists like D’Angelo and Erykah Badu. If the West Coast had G-Funk and the East Coast had boom-bap, the Soulquarians gave birth to a swirling, groove-oriented style that often sounded like a jam session in heaven.

Their shared astrological sign—Aquarius—was the playful basis for the group’s name, but it also symbolized a spirit of innovation and alignment. All the members had an almost psychic connection in the studio, bouncing off each other’s riffs, ideas, and random inspirations. You can hear the Soulquarian principles throughout Like Water for Chocolate: it’s there in the meld of live instrumentation, jazz-inspired chord progressions, dusty-soul beats, and the raw intimacy of Common’s lyrical approach.

Picture the Electric Lady Studios in the late ‘90s: you open a heavy, soundproof door, and inside is a swirling haze of incense, vibey lighting, half-finished lyric sheets, and vintage instruments scattered around. D’Angelo might be stationed at the keyboard, finessing a chord progression that’s halfway between gospel and funk. J Dilla might be hunched over his MPC, chopping up a sample from an obscure jazz record. On the drum kit, Questlove is testing out a new rimshot pattern while James Poyser tinkers on a Rhodes piano. In strolls Common, scribbling rhyme ideas in his notepad, eager to lay down a verse or just vibe to the groove until inspiration strikes.

This environment was the lifeblood of the Soulquarian sessions—collaborative, improvised, and fueled by collective energy. The typical boundaries between artist, producer, musician, and engineer often blurred; roles were fluid, and everyone contributed to the album’s overall mood. That synergy made each track on Like Water for Chocolate feel warm, cohesive, and organic—like a musical conversation that just happened to be documented in real time.

By the time Common joined forces with the Soulquarians, the Neo-Soul movement was already catching mainstream ears. Erykah Badu’s Baduizm (1997) set a new standard for confessional, jazz-inflected R&B, while D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar (1995) and Voodoo (2000) reintroduced the raw grit of 1970s soul to a hip-hop generation. These artists, alongside Ms. Lauryn Hill’s The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998), contributed to a sense that Black music was evolving past the radio-friendly formulas, heading into uncharted, more personal territory.

Common found himself in the thick of it, bridging the lyrical traditions of hip-hop with the spiritual depth and funk-laden grooves of soul and jazz. In many ways, Like Water for Chocolate became part of the Neo-Soul canon, even though it was stamped as “hip-hop” first and foremost. The album’s aesthetic—warm guitar twangs, lo-fi beats, introspective verses—resonated with fans of The Roots and Erykah Badu.

The same chemistry that fueled the Soulquarians would soon power a wave of classic albums in the early 2000s, breathing fresh life into Black music. Through their fusion of rap, soul, jazz, funk, and blues, the collective challenged genre lines and ignited a renaissance that influenced artists like Jill Scott, Bilal, Musiq Soulchild, and beyond. Common was no bystander; he was in the engine room, co-steering that movement and pouring every bit of Chicago grit and global curiosity into the music.

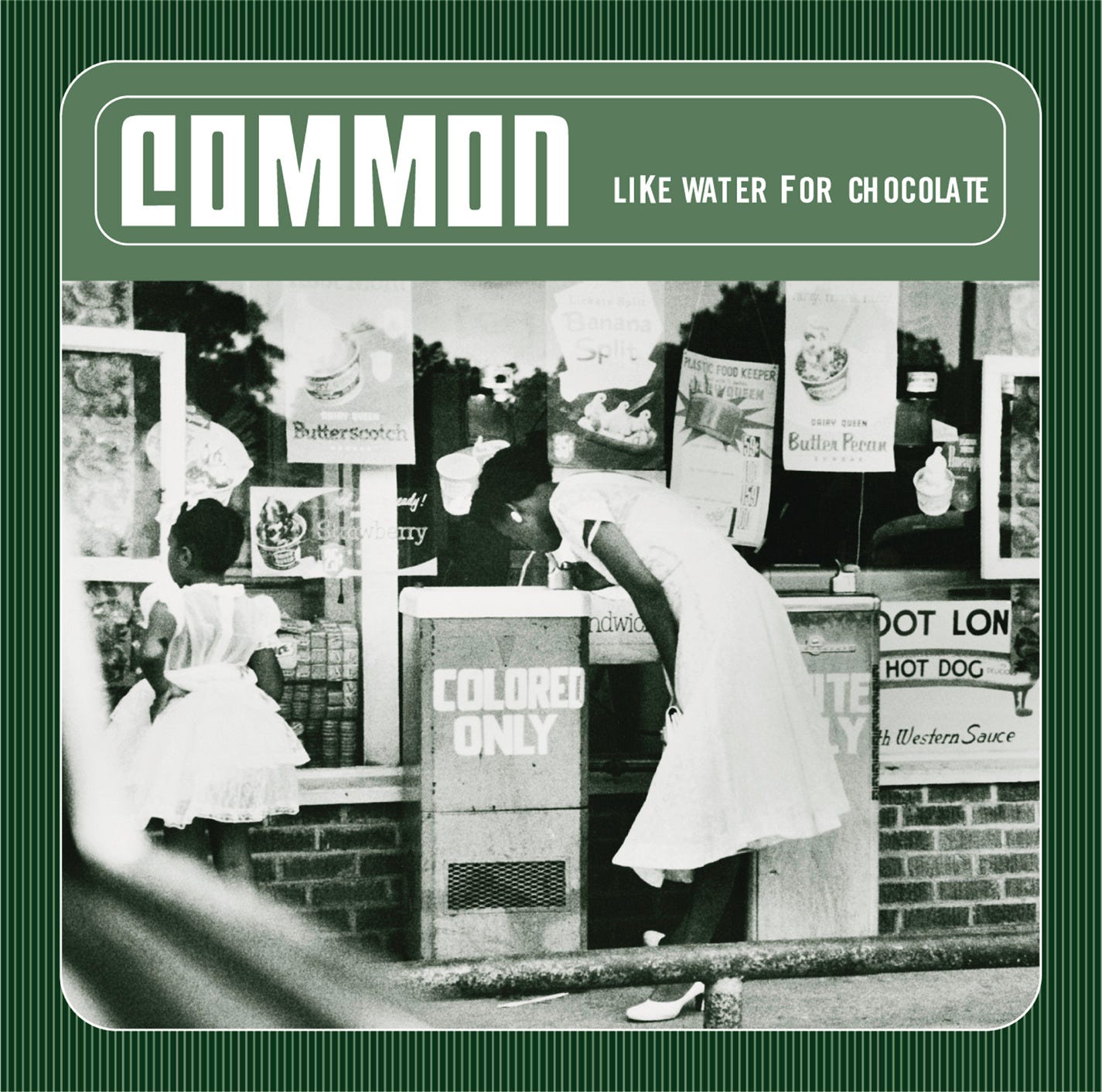

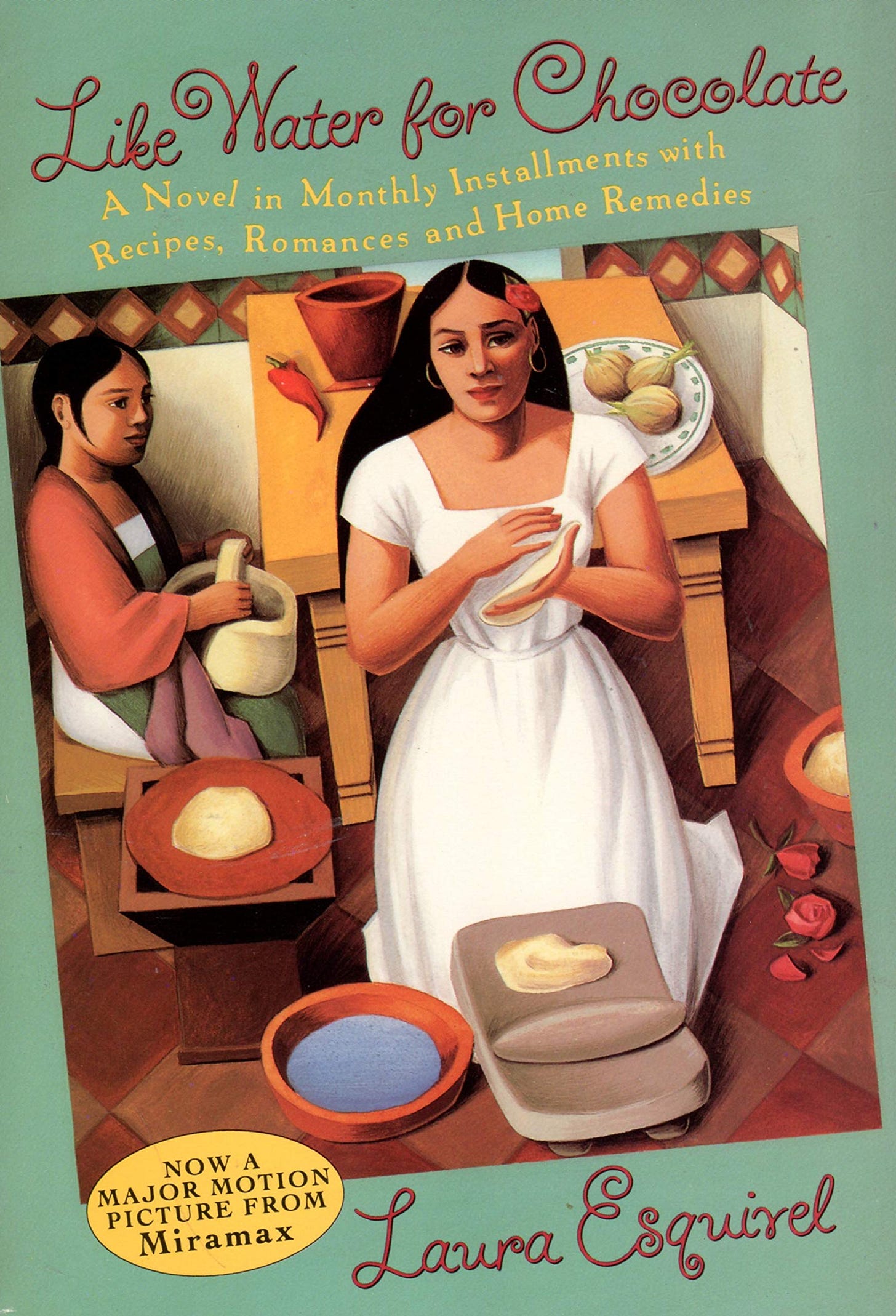

The first thing that often catches a listener’s eye about Like Water for Chocolate is its distinctive title. The phrase comes from Laura Esquivel’s novel of the same name—a story in which food and emotion are inextricably linked. For instance, a cook’s tears or passions can alter the flavor and effect of her dishes. Common chose this reference quite intentionally, alluding to the album’s simmering blend of personal reflection, social commentary, and musical fusion. Like the novel, this album is about more than just satisfying surface-level hunger; it’s about spiritual and emotional nourishment.

In Like Water for Chocolate (the novel), the phrase refers to a Mexican saying: water is heated to the boiling point when making hot chocolate, signifying heat, passion, and transformation. While Esquivel’s story centers on magical realism, romance, and family dynamics, Common takes these themes and transplants them into a hip-hop context. The “heat,” in this case, is both literal and metaphorical, symbolizing the creative spark in the studio and the incendiary social conditions affecting the Black community at the turn of the millennium.

The novel’s protagonist, Tita, communicates her deepest emotions through cooking—whatever she feels while preparing a dish is absorbed by those who eat it. For Common, music serves the same purpose: the vibe in the studio, the synergy among collaborators, and the raw emotion he pours into each verse flavors the album. By drawing on this literary reference, Common signals that this record is about creating art that doesn’t just fill a cultural appetite but resonates on an almost cellular level.

The concept of “heat” shows up in multiple dimensions throughout the album. Tracks like “Heat” itself pulse with undeniable energy, while others reflect an almost spiritual warmth—like the soulful glow of “The Light.” This heat is sensual, sociopolitical, and personal, reflecting everything from romantic connections to searing takes on injustice. In many ways, Like Water for Chocolate offers a fuller, richer exploration of the body, the mind, and the soul than previous Common albums. It’s nourishment for the whole self.

There’s also a subtle sensuality to the record. Songs like “Nag Champa (Afrodisiac for the World)” conjure scents, moods, and energies that transcend a typical “rap track,” veering into the tactile realm. Much like a hearty meal, the album is meant to be savored—listened to from start to finish, each track blending into the next, leaving you sated yet craving more.

Thematically, “Cold Blooded” takes us into darker territory. Common addresses the complexities of relationships tested by jealousy, betrayal, and ego—stories all too familiar in communities where survival sometimes trumps unity. The production is stripped down and murky, leaning on moody samples that underscore the tension. You can sense the emotional push and pull: Common aims to maintain integrity in a world where authenticity can be undervalued.

One of the defining elements of Like Water for Chocolate is how seamlessly it fuses samples with live instrumentation. You hear the classic turntable scratch here, a thumping bass guitar there, and perhaps some organ riffs or horns weaving throughout. This approach hearkens back to the golden era of hip-hop, rooted in crate-digging, while also pushing forward by inviting musicians into the studio to jam, improvise, and contribute new material.

The blend of live and sampled sounds not only evokes hip-hop’s past but also sets a new standard for what the music could become. Tracks like “Time Travelin’ (A Tribute to Fela)” invite Afrobeat influences—a direct nod to Fela Kuti—allowing the rhythms to stretch out and breathe. This bridging of genres—hip-hop, soul, jazz, Afrobeat—mirrors the cultural variety in a city like Chicago or any other metropolis where diverse traditions intersect daily.

“Dooinit” is a head-nodding, classic boom-bap track elevated by J Dilla’s off-kilter swing. Common’s flow is crisp and playful, reminiscent of his earlier works but sharpened by the confidence he’s accrued over three previous albums. Here, he’s flexing raw MC skills, reminding the underground faithful that he hasn’t drifted from the fundamentals of rap. Lyrically, he tosses clever brags and witty punchlines, but even the bravado carries an undercurrent of social critique, as the same goes for the DJ Premier-produced “The 6th Sense.”

Widely regarded as one of Common’s signature tracks, “The Light” is a love letter—literally and figuratively. Dilla’s production is a masterclass in sampling: he flips Bobby Caldwell’s “Open Your Eyes” into a warm, inviting groove that radiates optimism. Common’s verses are unabashedly tender, celebrating partnership, respect, and vulnerability in a way that’s still too rare in hip-hop. Laced with sweetness but never cloying, “The Light” captures that universal feeling of being inspired by someone who genuinely makes you better.

Teaming up with Mos Def (aka Yasiin Bey), Common engages in a lyrical ping-pong match on “The Questions” about life’s unanswerable riddles and everyday ironies, “Funky for You” marries the spirited experimentalism of neo-soul with a hip-hop backbone with Bilal and Jill Scott, Slum Village appears on “Payback Is a Grandmother” and “Thelonious” with MCs trade verses in a free-flowing cipher, and A Song for Assata” pays tribute to Assata Shakur, the activist and former Black Liberation Army member who famously escaped prison and found asylum in Cuba. Over a hauntingly beautiful instrumental, Common recounts her story with empathy and reverence, while Cee-Lo’s vocals add a gospel-like grace.

Recording sessions for Like Water for Chocolate took place in studios that valued creative freedom over pristine sterility. Tape hiss, vintage gear, and raw live instrumentation were welcomed, giving the album a warmth that’s often missing from digital-era productions. The Soulquarians’ approach was collaborative: musicians would come in and out, vibes would be tested, and sometimes entire songs would form from a single jam session or loop that felt right at the time.

This loose, jam-session energy didn’t mean a lack of direction. On the contrary, Common and the producers had a clear vision for what they wanted to achieve: an album that felt cohesive, like a single body of work, rather than a scattered collection of songs. Part of that cohesiveness comes from the trust and respect among the artists involved. You're guaranteed an extraordinary alliance in the room when you have individuals like James Poyser on keys, Pino Palladino on bass, and Questlove on drums.

Authenticity is a word often thrown around loosely, but in the context of Like Water for Chocolate, it rings true. Every note, every drum hit, and every verse had to resonate with the project’s overarching themes of love, community, and honest self-expression. That sense of realness emanates from each track, making the listener feel like they’re in the studio—smelling the Nag Champa incense, hearing the laughter of friends, and witnessing the creative electricity that can only occur when kindred spirits gather around a shared artistic pursuit.

Standout (★★★★½)