Go Down, Moses: The Era of Colonialism and the African Diaspora

Here’s an era of Colonialism and the African Diaspora with the establishment of slavery by the European powers.

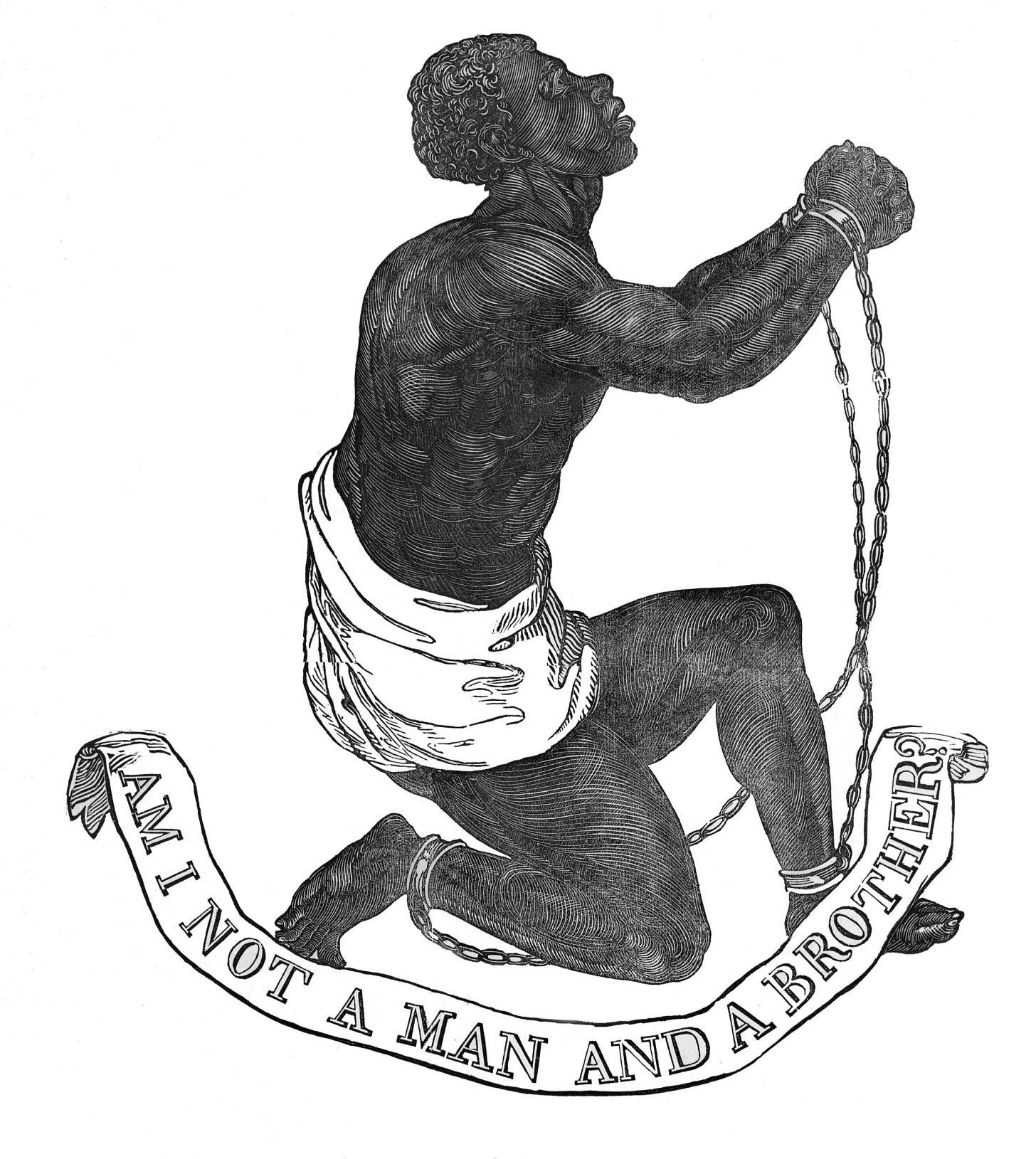

Slavery, and the trade that often accompanies it, has always been the bitter fruit of wars of conquest between peoples, driven by the desire to increase commerce and enrich the coffers of states and private companies. While it is true that in various forms the phenomenon has always existed, it is equally true that with the onset of colonialism, beginning in the 15th century, it reached new extremes in both scale and method. The European states started imposing policies of conquest far from their own territories, initiating the exploitation of new agricultural and mining lands with a local labor force that soon became coerced. In the Americas, as the areas to be exploited expanded, the need for more slaves outstripped the local supply, so new slaves were brought along preferential routes connecting Africa to the entire American continent.

During long and harrowing journeys, the Portuguese transported slaves from Angola to Brazil, the Spanish took them from sub-Saharan regions to Central and South America, while the French, Dutch, Danes, Swedes, and English deported them from the western curve of the Gulf of Guinea to North America. Over nearly five centuries of this trade, it is estimated that around thirteen million Black people were uprooted from their African homeland, forced to adapt to slavery while desperately trying to maintain at least a memory of their old traditions.

THE ‘CONQUESTS’ OF THE WHITE MAN

As Mark Twain said: “There is not a foot of land that does not represent the recurring and coercive expulsion of a long series of owners in favor of others.” The phenomenon of colonialism was nothing more than a large-scale confirmation of that reflection.

In all ancient civilizations, from Mesopotamia to Rome, the scourge of slavery was always the tragic fate of defeated peoples. It is the most immediate way for victors to display their power, knowing full well that the more ruthless the sentence—one that condemns the enemy to humiliation and exploitation—the greater the respect and fear they can instill in potential adversaries. Whenever a new power emerges, the slave market is shaped by the culture and needs of the aggressors. Thus, between the 15th and 17th centuries, when the Turkish and Ottoman Empires rose to prominence, the Mediterranean coastal settlements of old Europe—especially in Italy, Slavic regions, and Spain—were subjected to devastating raids that yielded spoils of valuables and human beings, all forced into a diaspora. Some estimates suggest that over a million Europeans were enslaved between 1530 and 1780. However, captivity could sometimes be ransomed through the fundraising efforts of confraternities and societies dedicated to redeeming slaves; there were also those who managed to win their own freedom through work, whether as domestic servants or in the baths of the Ottoman Empire.

Although persistent “literary legends” have handed down the stereotype of the so-called “white slave trade,” in reality nine out of ten slaves were men, because the market demanded masons, farmers, and especially rowers for the galleys. The Catholic Church, faced with the problem of slavery, has always taken a firm stand when it came to saving people who worshipped its own God, yet it showed greater hypocrisy when dealing with those of other faiths.

A definitive stance arrived only in 1639, when Pope Urban III forbade the enslavement of the natives of Latin America and the West Indies—then under Portuguese rule—on pain of excommunication. This provoked such indignation among the Lusitanian rulers and slave traders that they expelled the Jesuits from Brazil. In the 17th century, in fact, the slave market had already become the norm and fueled a well-established market economy, which was difficult to dislodge. Of slaves from Africa, however, not a word was spoken.

“Man does not know how to migrate. He colonizes or invades without scruple.” — Silvia Zoncheddu

In the same period, Anglican and Calvinist countries—such as England, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands, far less bound by the Church’s dictates on slavery—landed in the New World and proceeded with the same cynicism and determination, filling both state coffers and those of private shipping companies with gold through the deportation of slaves. Even when, in 1807, the English signed the abolition of the slave trade, the trafficking continued for decades under other nations. It would take the advent of Napoleon in Europe to bring an end to the deportations truly.

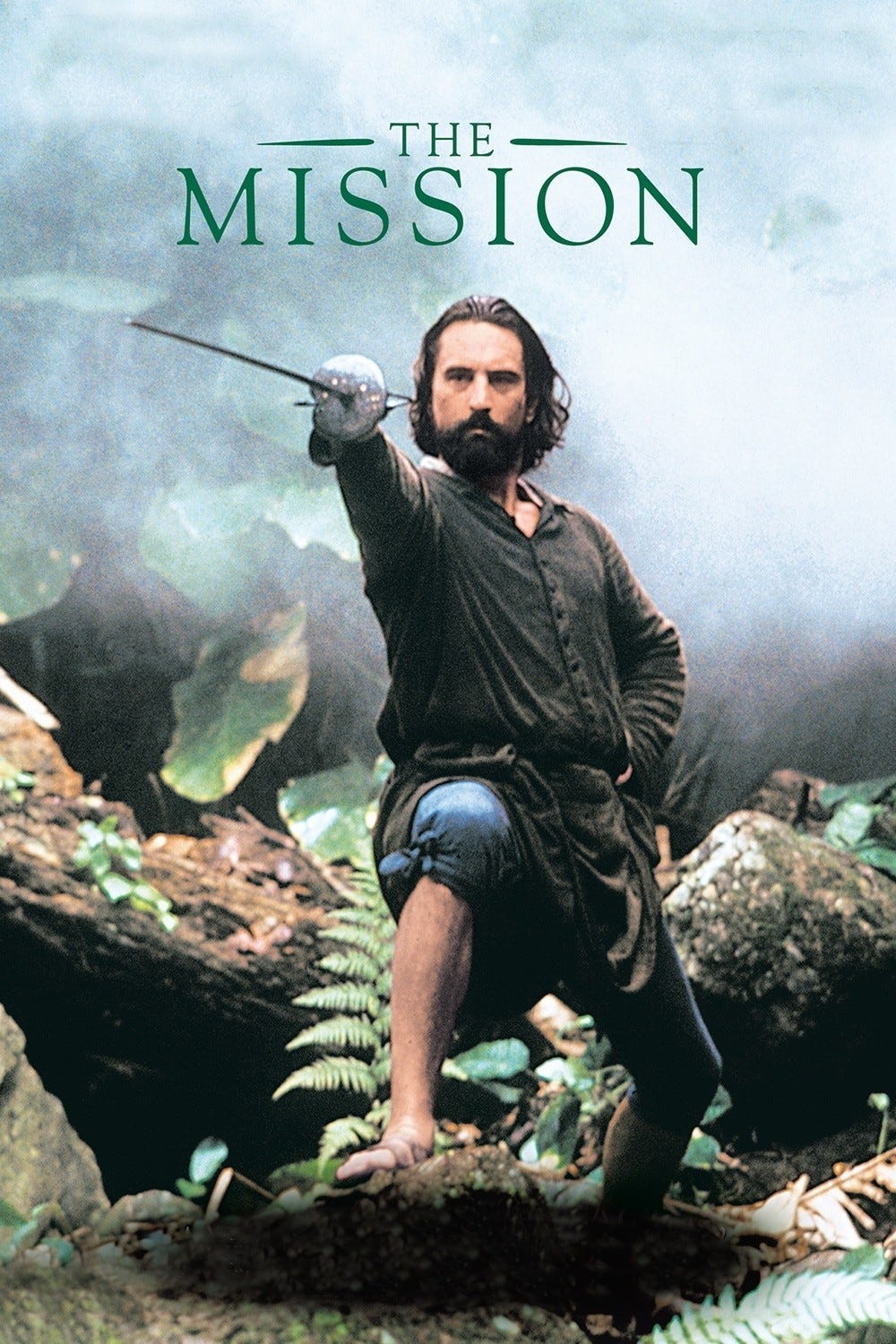

THE MISSION

REASONS OF STATE OVERRIDE RELIGION

Between 1608 and 1767, in a vast territory nestled between the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers, the Jesuits carried out a remarkable attempt at evangelizing the Guaraní people—an endeavor so extraordinary that it defies easy comparison. The Society of Jesus managed to establish a kind of large community in which the Indigenous inhabitants could work and enjoy the fruits of their labor, living a peaceful existence unlike anything else under Spanish and Portuguese rule. This tranquility was soon disrupted by mercenary bands in the service of the Iberian conquerors, who scoured the region for forced labor to supply their plantations. Matters worsened when Ferdinand VI of Spain ceded a large portion of those lands to the Portuguese: the attacks multiplied with such ferocity that it resulted in outright genocide. The Jesuits petitioned Pope Clement XIII, who dispatched observers to assess and report on the situation. Despite confirming both the Jesuits’ impressive work and the successful evangelization of the tribe, the Pope, facing insistent demands by the Lusitanian governors—who even threatened to expel the Order from all of South America—acceded to political pressure and ordered the Society of Jesus to abandon the community. Bereft of external support and with only rudimentary weapons, the Indigenous people tried to defend themselves, only to be pillaged and massacred.

The Mission, the 1986 film by Roland Joffé, accurately portrays—albeit in broad strokes—this failed Jesuit enterprise and the subsequent tragic events. It underscores how, even for the Church, reasons of state eventually triumphed over the most fundamental religious principles of love and respect, which the Pope is meant to safeguard. The memory of that marvelous experiment, begun under the banner of the Gospel, survives only in the eyes and minds of a few scattered children who escaped the massacre.

Deeply Catholic Spain and Portugal, straddling the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, profited from their great explorer-navigators’ geographic discoveries—and from a presumed duty to bring civilization via evangelization—to become the first European powers to colonize newly discovered lands, often violently subjugating their inhabitants to serve their ambitions. Millions of Indigenous people were enslaved to mine precious metals and work the large agricultural plantations carved out of their own lands. They had the backing of the highest religious authority, Pope Nicholas V, who, by the mid-1400s, had declared that the pagan peoples of Africa must be converted—even by force if necessary—and that all their possessions should be confiscated.

For strategic reasons, Spain and Portugal agreed to carve up almost all of Central and South America between them to avoid economic conflicts of interest. They called on Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) as an impartial arbiter, and with a method both rough and effective, he decreed that all coasts to the east of an imaginary line running through the Atlantic Ocean 370 leagues west of Cape Verde would belong to Portugal, while everything to the west—including adjacent territories—would belong to Spain. This famous 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas governed the division of the world for many years.

EL DORADO

A RITUAL THAT BECOMES LEGEND

At the root of the El Dorado legend likely lies the memory of a sacred ritual performed by the Andean Muisca (some sources say Chibcha) people inhabiting Lake Guatavita, north of Bogotá in Colombia. Their leader was required to renew each year an ancient tradition in the presence of the entire population. After covering his body with mucilaginous algae, he would sprinkle himself with gold dust and immerse in the lake’s waters, offering this supposedly magical dust—and other treasures, all made of gold—to a deity. Rumors about the leader’s glittering appearance during this ceremony gave rise to the legend of El Indio Dorado, later shortened to El Dorado. When the first conquistadors caught wind of this ritual, it swiftly morphed into a kind of mirage, which over time took on increasingly fantastical qualities until it became a fabled locale of immeasurable wealth that enticed adventurers from far and wide.

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, a conquistador, was the first to reach this much-dreamed-of place in 1536, plundering the local population but failing to unearth any of the legendary treasures. Questioned about the existence of this paradise, the natives—likely hoping to be rid of their destructive visitors—confirmed its existence but directed them to a safe distance away. Of course, nothing was ever found, and El Dorado remains the metaphor of an imagined, fabulously wealthy America awaiting conquest.

By the seventeenth century, the Dutch, French, and especially the English had joined Spain and Portugal, with the English gaining near-monopoly over the African slave trade in the following century. Up to the nineteenth century, approximately twelve and a half million Black people—40 percent men, 35 percent women, and 25 percent children—were shipped across the Atlantic, most bound for southern U.S. ports. It is estimated that over two million died en route from disease and dire conditions. Economic interests drove these European powers to practice slavery, generating massive profits for the nobility. The nobility showed no scruples in divvying up these profits while leaving much of their own populace in abject poverty. The pursuit of El Dorado—whether literal or figurative—was widespread, taking on countless forms depending on the region and its resources. Yet the outcome was invariably the same: hunger and destruction for the powerless, bountiful returns for the powerful.

“When the white people arrived, they had only the Bible, while we had our land. They taught us to pray with our eyes closed: when we opened them again, the whites had our land, and we had the Bible.” — Jomo Kenyatta

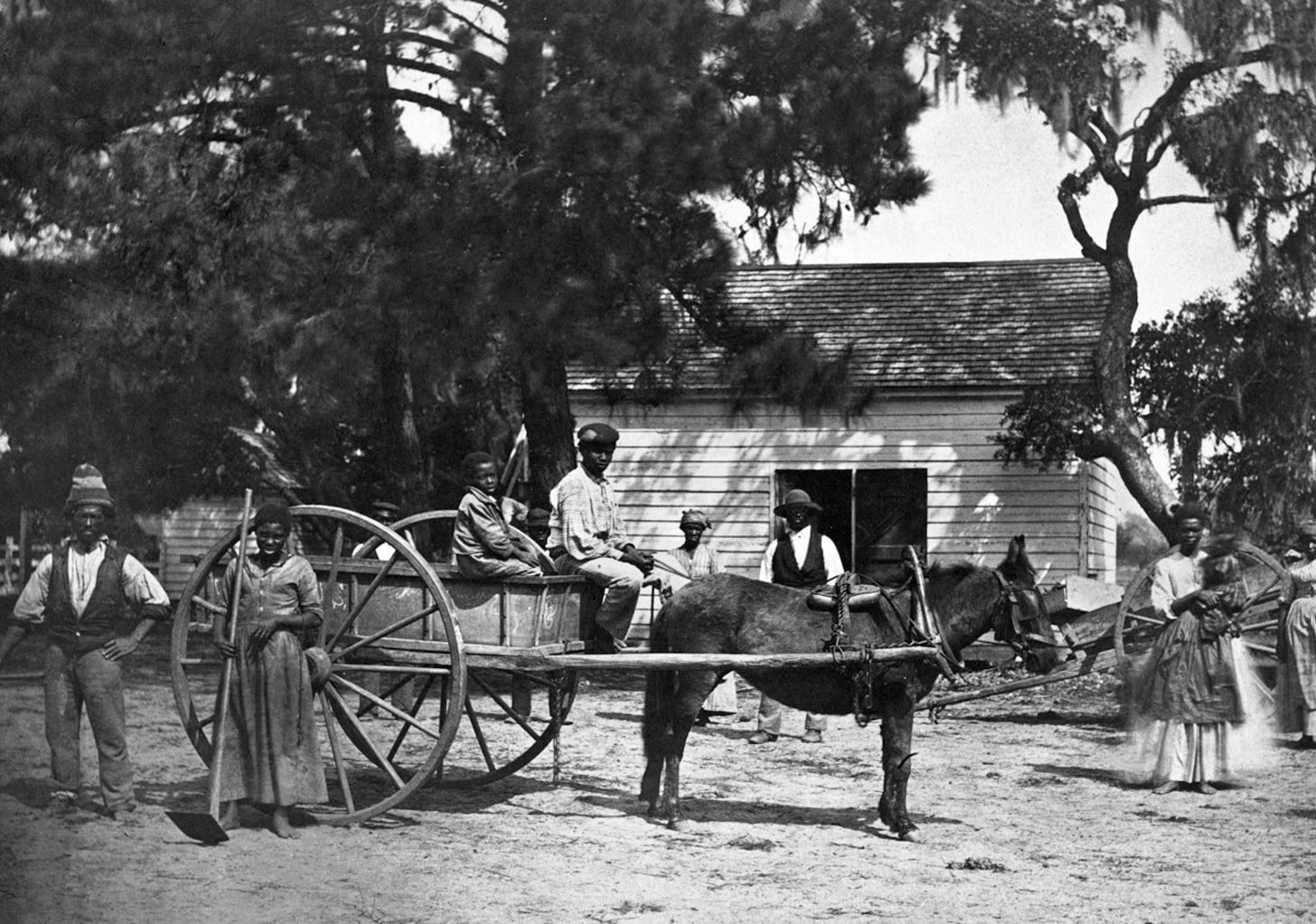

In these “new worlds,” slavery was managed systematically to forestall rebellion. Peoples of differing ethnicities were deliberately intermingled so that language, culture, and religion could not coalesce into dangerous assemblies. Varying by region, ethnic mixing was encouraged, banking on ancient tribal hostilities to breed distrust and insecurity. To further sever bonds of identity, families were broken apart. It was a sentence to isolation and exploitation, mitigated only by Christian teaching that stressed resignation and submissiveness, promising sure redemption in the hereafter.

Many slaves did convert to Christianity; others, however, engaged in the striking practice of developing their own liturgies that concealed African deities beneath Christian saints—an ingenious synthesis that eased their masters’ suspicions while preserving at least part of their ancestral beliefs. Hence the emergence of Haitian (later New Orleans) Voodoo, Brazilian Candomblé, and Santería in the Caribbean, where outwardly innocuous public rituals masked more deeply rooted spiritual practices carried out clandestinely. Unlike Western faith traditions, African religions generally exhibit no rigid dualism between body and soul, instead adopting a holistic worldview in which every aspect of life is interconnected, all in pursuit of harmony—even cosmic balance. Through religious rites, practitioners seek union with the universal. The cosmos is envisioned in two realms: the sky (orun), home to the deities (orixá), and the earth (aiè), inhabited by humanity.

“Colonialism and slavery enabled the rise of capitalism.” — Angela Davis

LA KORA

AN INSTRUMENT BESTOWED BY THE GODS

Tracing the kora’s origins means journeying back to the thirteenth century when Mali’s empire spanned the Sahel under the wise rule of Sundiata Keita. One of his generals, Tiramakhan Traore—renowned for conquests in the empire’s western reaches—once heard an enchanting sound emanating from the caves of Missirikoro. The beguiling tones came from a kora: a half-gourd hollowed out and covered with soaked, stretched goatskin, into which a long wooden neck was inserted. Ten strings, running from the neck to a small bridge on the gourd, produced an otherworldly resonance. A female deity, credited as the instrument’s inventor, was playing it. Mesmerized, the general seized the kora and commanded his griot, Djelimali, to learn how to play. Djelimali did so, teaching his son Kamba; from father to son, the knowledge eventually reached Tilimaghan Diabaté, who introduced the instrument throughout Mali. The kora soon transcended national borders, spreading across the Sahel.

Modern kora construction adheres to precise proportions defining the neck’s nature and length, as well as the number of strings, which have grown to twenty-one. Traditionally, only the village griot—the oral custodian of a people’s history and culture, akin to the ancient Greek aoidos or Celtic bard—plays the kora, passing down the legends of their ancestors in song.

One ancient oral myth recounts that heaven and earth were once united in a single mass, until a child accidentally soiled the orun (heavenly realm), provoking the wrath of the supreme deity, Olorun, who used divine breath to forever separate sky from earth. That primordial union can be restored only through religion. In parts of Brazil known as terrieros, where Candomblé thrives, one may still find imagery reflecting this ancient worldview, like a gourd cut in half: the bottom symbolizing earth (the feminine principle) and the top, sky (the masculine). In reality, these two halves intersect, allowing the universal to flow into the particular and vice versa. A demigod, Exù, acts as the intermediary between gods and humans.

Many forces shape human relationships, but above all the word (not merely as logos or semantic content) is understood as a vehicle of vital energy—axè—that transits between individuals, underpinning their very connection. Hence, the word is communication and, by extension, creativity and art in all its forms. Through music, dance, and poetry, one communes with the world as a totality, each artistic discipline a single thread in a grand tapestry. This concept emerges clearly in African polyrhythm and polymeter. Repetition of rhythms anda phonemes conjures a mythical era devoid of division. In rituals that call upon this collective memory, rhythm is the fundamental tool for introducing spiritual power into the tangible world. Every living being has a unique rhythm, a “sound identity” that must be sung out to join the endless temporal flow where beginnings and endings converge. In the African worldview, time is cyclical, born of lived experiences rather than an abstract, transcendent measure; it can shift meaning in different cultural contexts. Within communal rituals, each participant inhabits a personal sense of time, fully immersing in the sacred action.

FROM AFRICA WITH DISHONOR

Early in the 17th century, the English landed in Virginia and methodically began colonizing the surrounding areas, wresting New Amsterdam from the Dutch and rechristening it to New York. They would dominate the slave trade from Africa to what is now the United States throughout the late 1600s and early 1700s until they were eventually supplanted by American traders.

It was the Protestant Reformation—and the concurrent decline of the Spanish and Portuguese empires—that opened the door for France, England, and the Netherlands to carve out their own territories in the Americas. By then, however, the Iberian powers already ruled most of the continent, leaving only the northern expanses for the newcomers to settle. Thus, if English and French are spoken in America today only north of the Rio Grande—and in a few linguistic enclaves in Guyana or Belize—part of the blame (or credit) belongs to Pope Alexander VI, who orchestrated the Treaty of Tordesillas.

In 1607, having been granted a charter by King James I to found colonies in North America, the Virginia Company fitted out three ships that sailed from London with adventurers seeking fortunes in the New World. The crew included many prisoners who accepted the voyage in exchange for freedom upon arrival. They landed in Jamestown, Virginia, establishing the first permanent English settlement on American soil. Despite myriad hardships—not least conflicts with Indigenous tribes—Jamestown became profitable, exporting timber and cultivating tobacco. Soon, however, labor demands escalated; in 1619, the Virginia Company imported another thousand indentured servants, among them twenty Africans with the same legal status. Under indentured servitude, still colorblind at this stage, people were freed after a set term (typically four to seven years) with no financial reward—time considered repayment for their transatlantic passage. Once released, they could independently pursue a livelihood, and their children were born free with equal legal standing. No laws then restricted interracial marriages among Blacks, whites, or Indigenous people; each individual could marry as they chose.

From 1640 to 1650, it was not unusual near Jamestown to see farms owned by well-off Africans who themselves employed indentured servants. Things deteriorated soon afterward when large plantation owners realized temporary servitude was not financially advantageous. In 1662, after Massachusetts became the first colony to legalize slavery, Virginia mandated the deportation of all free Blacks and declared all remaining Africans in the colony to be slaves. By 1776, when the Thirteen Colonies declared independence from England, human chattel had already been enshrined as private property—justified by the alleged superiority of the white race.

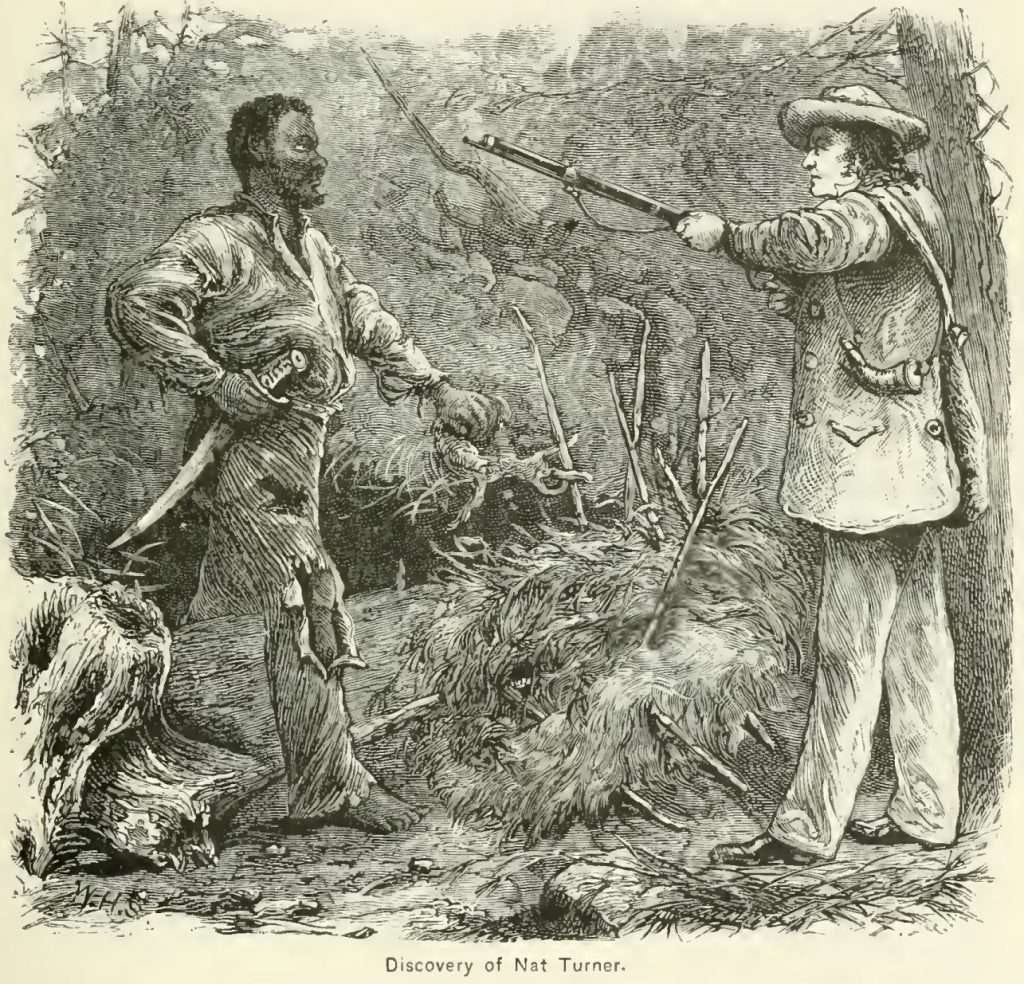

To uphold this slave system, legislation imposed strict social controls on Black people, prohibiting free movement, assembly, and education. Any attempts at resistance or insurrection among enslaved workers were met with vicious bloodshed and severe reprisals. One infamous example is the 1831 revolt in Southampton County, led by the enslaved preacher Nat Turner, which culminated in over two hundred enslaved people being killed—far exceeding the number of actual participants.

A NEW LIFE ATTEMPT

THE ACS AND THE FOUNDING OF LIBERIA

On December 21, 1816, at the Davis Hotel in Washington, an extraordinary event took place. With the backing of evangelical Christians and abolitionists, Henry Clay (a member of the Virginia House of Delegates) met with Supreme Court Associate Justice Bushrod Washington and Presbyterian minister Robert Finlay to establish the American Colonization Society (ACS), a private organization dedicated to creating a “promised land” in West Africa for the United States’ free Black population (former slaves).

Symbolically, they chose the same region along the Pepper Coast that had once served as the main embarkation point for slave ships three centuries earlier. The colonists would rename the land Liberia. From the outset, they faced daunting challenges: harsh tropical climates, disease, and frequent clashes with local inhabitants whenever they tried to expand. Of the more than 4,000 people who arrived in 1820, half would die within twenty years.

In 1822, another ten thousand former slaves joined this pioneering group, leading to the founding of Monrovia, named for U.S. President James Monroe. Yet the hoped-for exodus never really materialized, as many free Blacks chose to remain in America rather than brave such austere circumstances. Liberia remained underdeveloped and small—home to barely 13,000 people, most reliant on ACS subsidies. When the organization went bankrupt in the early 1840s, the U.S. government refused to declare sovereignty over the colony and explicitly requested that Monrovia declare its own independence. On July 26, 1847, Liberia thus became the first African republic founded on ideals of liberty and racial equality, adopting a constitution closely modeled on America’s. Its first president was Joseph Jenkins Roberts.

As the United States rapidly expanded westward and global demand for tobacco and especially cotton soared, the need for enslaved labor intensified—along with new deportations from Africa via the triangular trade. English slavers departed Bristol and Liverpool laden with weapons, cloth, liquor, and assorted trinkets to exchange in African ports for enslaved people captured by warring local tribes. From there, the ships followed the route to the Americas, where captives were traded for raw cotton and tobacco that returned to England for processing. This completed the tragic triangular voyage, endlessly repeated. Profits were immense, prompting King William III to abolish customs duties on slaving and permit “the human trade” to any private company, thereby competing with the royal monopoly previously held by the Royal African Company.

By the early nineteenth century, two divergent economic models dominated the U.S. The North, having industrialized, had abolished slavery, replacing it with wage labor—recognized by capitalist logic as a new exploitable class. To protect domestic production and industry, the North adopted protectionist measures with tariffs on imports. This alarmed the South, which depended on an agrarian, slave-based economy and risked endangering its trade with Europe, especially England, whose burgeoning textile industry required immense raw-material imports.

Rising tensions from this socioeconomic chasm erupted in 1861 in the Civil War. The industrial North triumphed, imposing the abolition of slavery—albeit a formal abolition that soon eroded, leading to conditions for Black people arguably worse during the South’s period of reintegration than they had been under enslavement. In the brief window of freedom, however, a Black middle class emerged, only to distance itself from the underprivileged who again found themselves isolated and persecuted. The brutal Jim Crow laws—enforcing racial segregation and stripping away human rights—were enacted in the southern states by the late 1890s. In his work Slave Law in the Americas, historian Alan Watson describes how the U.S. legal approach to slavery was shaped locally over time, influenced by court precedents and ad hoc statutes rather than directives from England. While Roman law sometimes served as a reference, it left control of enslaved individuals to private masters rather than the state.

The 1690 Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves, adopted in South Carolina, states:

“If a slave or an Indian commits any act of violence upon a white person, for the first offense he shall be severely whipped by order of any justice of the peace; for the second offense, he shall be severely whipped again, have his nose cut off, and be burned in the face; for the third offense, sentencing is left to two justices and three freeholders, who may inflict death or any other penalty at their discretion, unless the act of violence was committed at the request or in the defense of the master.”

With independence from England, the treatment of enslaved people changed considerably. For instance, no legislation then spelled out their rights and obligations, granting slaveholders unfettered authority. An 1805 publication offered five guidelines to create the “ideal slave”:

Maintain strict discipline and unconditional submission.

Instill a sense of inferiority, ensuring they know their “place.”

Instill fear in their minds.

Instruct “servants” to be invested in the master’s affairs.

Deprive them of education, community support, and independence—no schooling or entertainment.

Only when rebellions and escapes became more frequent did owners slightly improve conditions to curb unrest. Summer workdays were trimmed to fifteen hours, winter to fourteen, and Sundays were free for religious observance. The Church played a key peacemaking role but also stoked fear of masters, preaching the devil’s wrath on slaves who broke the rules. American Protestant denominations had endorsed slavery since 1637 when the trade began.

Calvinist and Puritan ethics—brought by persecuted Protestant separatists fleeing the Anglican Church—underpinned this system. Their belief that civil and religious morality were one and the same, entrusted to each individual’s conscience, helped rationalize slavery. Under Calvinism, personal “superiority” was seen as divinely ordained, justifying the subjugation of Black people, ostensibly descendants of Ham, Noah’s cursed son.

African Americans responded by creating partly religious songs, the spirituals, and partly secular songs, the blues—the latter becoming their first true cultural expression. Here was a self-sufficient, indispensable means to narrate lives uprooted by dramatic historical and social forces that had torn them from their land and customs, enslaving them in a world whose language and geography they did not know. This was the tangible nightmare they learned to endure, forging a precarious balance between adversity and redemption in song. Melancholy yet rife with dignity, the blues spoke to the world of total disenfranchisement, of losing every right and shred of humanity.

Initially, these songs were not yet “the blues,” emerging instead as field hollers, cries, and shouts that channeled an interior realm in turmoil, broadcast to neighboring laborers suffering the same hardships. It was a means of communicating emotion and of remembering they were still alive—and not alone. These primitive, loosely structured vocal calls, often repeated without logical sequence, were chanted in hopes of an echo from a comrade picking cotton or plowing nearby. True blues developed after emancipation, when the Civil War had freed enslaved populations—only to leave them jobless and homeless. On the dusty roads, the group chorus once echoing a solo voice gave way to the guitaras accompaniment. Different regional styles arose, often guided by local “masters” or influenced by popular white music. The most archaic was the Mississippi Delta style—rough, percussive, and unrefined yet powerfully direct. Each region had its own variation, unified by acoustic instruments. Electrification arrived in the 1940s, pioneered by Muddy Waters in Chicago, forging a more frenetic, urban blues that resonated with city life—instantly popular and widely imitated.

THE MASON-DIXON LINE

A SYMBOLIC BORDER

What we now call the Mason-Dixon Line, the cultural boundary dividing the Union and Confederate states during the Civil War, actually dates to 1763. It was devised to settle colonial disputes between two aristocratic English families—the Penns and the Calverts—both granted New World territories by King Charles I. Charles Mason, an astronomer, and Jeremiah Dixon, a mathematician, served as impartial arbitrators to mark the boundaries between Pennsylvania and Delaware (both Penn domains) and Maryland (controlled by the Calverts, who claimed the entire Chesapeake Peninsula). Drawing on complicated calculations and royal directives, Mason and Dixon established lines all parties finally accepted. This demarcation later gained momentous significance during the Civil War: Pennsylvania, north of it, joined the Union, while Maryland and Delaware, south of it, joined the Confederacy.

Extending westward to what was then the Texas frontier, this line held enormous political weight, determining how many states belonged to the industrial North or the agrarian South. Because congressional representatives were allocated based on the population of free men, the Southern states risked losing influence unless they could count their enslaved population. Hence, the Three-Fifths Compromise counted enslaved people at three-fifths their total number, granting the South more seats than it would otherwise have. Nonetheless, it was insufficient to freely legislate without northern opposition. Soon after, South Carolina—feeling economically stifled—seceded, joined by other slave states to form the Confederacy.

Thus, slavery emerged more as a political pretext than an ethical quandary, serving northern capitalists who wished to replace enslaved labor with wage labor. The latter, being paid, could become consumers, fueling the economy.

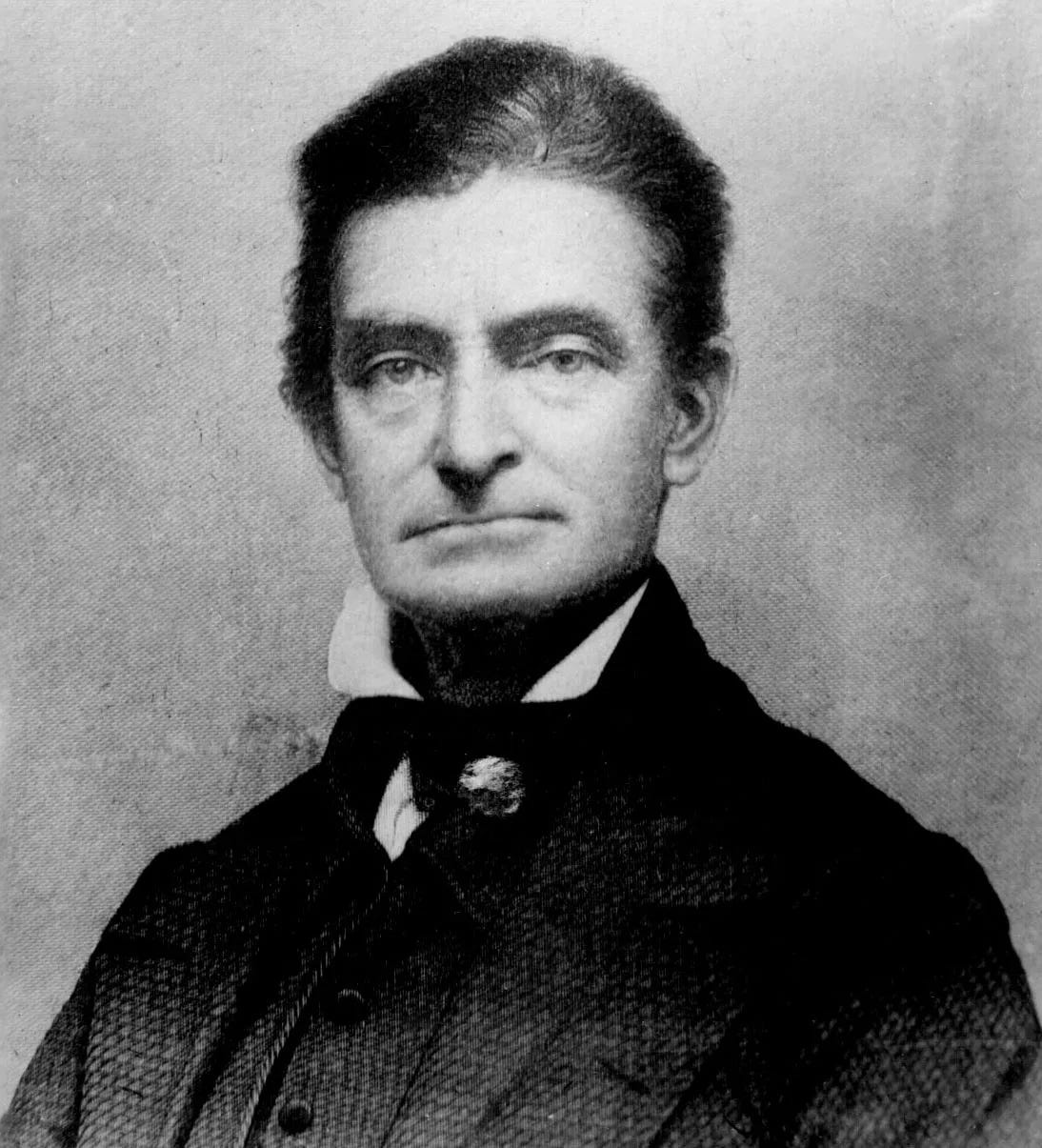

JOHN BROWN

A LEGENDARY ABOLITIONIST

To understand John Brown, a passionate abolitionist, one must examine the historical backdrop of the early 1800s. Slavery was among the most urgent and knotty issues confronting the U.S. Congress. Since the 1776 Declaration of Independence, the Union had admitted states in pairs—one free, one slave—to maintain Senate balance (each state, regardless of size, gets two senators). In 1820, for example, when slaveholding Missouri was allowed to join the Union, lawmakers responded by carving out Maine from Massachusetts as a free state to preserve equilibrium.

Things got more complicated in 1854 with the creation of Kansas and Nebraska, where settlers were permitted to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. Violent clashes erupted between these pro- and anti-slavery factions, notably in Lawrence, Kansas, which was sacked by slaveholders led by Sheriff Samuel J. Jones. In retaliation, John Brown—already supporting the Underground Railroad (the clandestine system that ferried enslaved people from the South to freedom in the North) and advocating armed insurrection as the only sure path to eradicating slavery—killed five pro-slavery settlers at Pottawatomie in May 1856. His raids continued for three years, culminating in a failed attempt to incite an uprising in West Virginia. After attacking the Harpers Ferry arsenal to seize weapons for the revolt, Brown was captured and hanged.

The 1861 song “John Brown’s Body,” commemorating these events, became a rallying cry for the Union cause, so popular that Union soldiers used it as a battle hymn. Upon hearing their marching chorus, Julia Ward Howe composed “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to the same tune, infusing a personal religious mysticism but retaining the famous refrain—“Glory, glory, hallelujah, his soul goes marching on”—still widely recognized today, second in patriotic status only to “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

What endures from earlier eras is the uniquely Black mode of communication—its particular vernacular and keen sensitivity—ever-attuned to new struggles that never truly ceased. Because of its ability to probe the depths of human emotion, the blues soon became, for many white musicians too, the most immediate form of personal expression. It was at that moment that the blues finally gained global acknowledgement.

“Sometimes you ask God for something, and you don’t know what you’re asking for.” — Mahalia Jackson

Your coverage is fascinating! Thank you for sharing.